Nguyen Cao Ky, the former Air Marshal and Premier of Vietnam passed away six years ago this month. I got to know Ky during the final days of the war in 1974-75 when the North Vietnamese were rolling south almost unimpeded. Eventually, they encircled Saigon and thousands of Vietnamese, including Ky, fled their homeland. It was a bitter pill for Ky to swallow, but even he could see the end was inevitable. I posted the following story about Ky the week that he died. I am reposting it today as an anniversary tribute.

When I heard the news of former Vietnamese Premier and Air Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky’s death, I was immediately whisked back to Saigon about a month before it fell to the Communist North Vietnamese in April 1975.

It was March 27, and I had gone to visit Ky at his sprawling home on Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut air base.

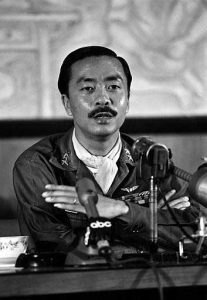

He greeted me wearing the black pilot’s flight suit and purple scarf he liked to be seen in. I had never met Ky before, but I had heard a lot about him. Stories said he was a swash-buckling “Top Gun” kind of guy who never backed down from a fight and had a reputation as a womanizer.

He may have been all of those things, but the day I met him he was pensive and worried about the future of his country–as well he should have been. North Vietnamese troops were less than 50 miles from Saigon and every day they were pushing South Vietnamese forces further south.

For those unfamiliar with America’s war in Vietnam, Ky was a staunch American ally during that conflict. But even more than that, he was a combat pilot who eventually became the head of Vietnam’s Air Force and in 1965 became Vietnam’s Premier–a post he held until 1967.

From 1967 to 1971 Ky served as Vietnam’s Vice President under Nguyen Van Thieu–South Vietnam’s last president.

When we met in 1975 Ky had been out of Vietnam’s political scene for almost four years–preferring to sit on the sidelines. Nevertheless, he still had tremendous support from Vietnam’s Air Force and probably could have led a successful coup against President Thieu, who was under heavy fire for a strategy that called for abandoning the Central Highlands of Vietnam and allowing the North Vietnamese to take control of a large part of South Vietnam.

“That was, without doubt, a major military error,” Ky told me. “And President Thieu must live with that decision the rest of his life. In fact, it may turn out to be South Vietnam’s death knell. I do believe Thieu should resign, but I am not in favor of a military coup. Vietnam must remain united in the face of the onslaught from the North.”

We walked around Ky’s compound, and as we did, he pointed to a helicopter sitting nearby.

“See that?” he asked, pointing to a HUEY helicopter. “That is my last resort. If the Communists reach Saigon, I will take my family out in that chopper.”

That is exactly what he did–landing on the deck of the USS Blue Ridge on April 29, 1975.

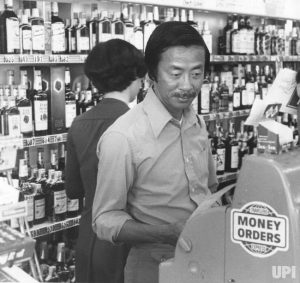

Eventually, Ky wound up in Southern California, and in 1980 I met him again at his house in Westminster south of Los Angeles. He owned and operated a liquor store and was living in a 3,000 square foot two story Spanish-style home in a nice upper middle-class neighborhood.

During his time at the top of Vietnam’s political pyramid he, along with other Vietnamese officials, were often suspected of profiting mightily from the $686 billion (in inflation adjusted dollars) Washington poured into the South Vietnam between the early 1960s and 1973 when the Vietnamese peace agreement was signed in Paris.

When I asked Ky about such allegations, he bristled. He still had his distinctive black mustache but had lost the black flight suit.

“If I had stolen millions of dollars would I be here operating a liquor store?” he asked. “Wouldn’t I be living like some sultan or king? Wouldn’t this modest house be a palace?”

Ky paused to light a cigarette and then continued. “Look, I am not a born politician. I am an artist, a flyer, a romantic. Back in 1967 I was very active in Vietnam, and I could have been president, but I stepped aside in favor of Mr. Thieu. I am just not a political animal.”

Nevertheless, about a month before South Vietnam’s fall, Ky was coaxed out of retirement to be part of a new “Government in Hiding.” That unofficial entity had at first attempted an unsuccessful bloodless coup against President Thieu then when several were arrested, it went underground in a bid to gain power before the North Vietnamese entered Saigon. Ky was not arrested because Thieu feared (probably correctly) that the VNAF would come to his aid.

As we sat in KY’s compound on the outskirts of Saigon that March afternoon in 1975 we could hear the sounds of North Vietnamese artillery and mortars pounding South Vietnamese positions less than 10 miles away.

“It is only a matter of time,” Ky told me. “Realistically, the NVA could come into Saigon anytime. But I think they are waiting to see if Thieu will step down. And I also believe they still are not quite sure what the Americans will do if they do roll into Saigon. After all, they are in violation of the 1973 Peace Treaty–though I have yet to meet a Communist who honors any treaty.”

I asked Ky if he was bitter at what many South Vietnamese considered a betrayal by Washington when it pulled its last combat troops out of Vietnam in 1973.

“I am not bitter about America’s involvement here, but I am bitter about the fact that her policy makers never listened to my advice,” he said. “That is a glaring weakness with American foreign policy. Washington politicians and bureaucrats think they know more than the natives of a country like Vietnam when in fact, they don’t. That is the arrogance of Washington, and in my opinion, it is an attitude that will always get America into trouble in countries they know very little about.”

Of course, at the time neither of us had any idea that America would eventually invade Iraq and become embroiled in Afghanistan in what has turned out to be the longest war in American history.

“I have consistently told Washington you cannot win a defensive war in Vietnam when the other side is engaged in an offensive war,” Ky said. “By fighting a limited, defensive war, the U.S. allowed the North Vietnamese to continuously re-supply their units in the field. Why did they do this? Because weak politicians in Washington were terrified that the Communist Chinese might intervene if the U. S. got serious about defeating the North Vietnamese. They didn’t want a repeat of the Korean conflict.

“The worst thing that happened to South Vietnam was when we allowed the United States to take control of our war with the North,” Ky said. ” Long before America decided to quit the war, I realized that this would be the inevitable result of America’s lack of commitment to victory. I offered to lead a South Vietnamese attack on North Vietnam, which was defended by a single division of regular troops. All I required from the US was air support, and that the us forces already in Vietnam would defend population centers. My purpose was not to conquer, but to force Hanoi to withdraw its divisions from the South to defend the North, and thus to bring about genuine peace negotiations.”

Ky shook his head and stubbed out a cigarette.

“Would you like a 33?” he asked, referring to the popular Vietnamese beer. He retreated to the kitchen of his compound and returned to with two half-liter brown bottles of “33 Biere.”

“You know, any military strategist with any training knows that the best defense is a good offense,” Ky continued. “But even our defense was passive. So-called ‘Search and Destroy’ operations were kept within South Vietnam’s borders. Enemy territory was always a safe rear base. The North Vietnamese also used neighboring Laos and Cambodia to establish lines of communication, supply bases, recuperation centers for their troops. The enemy general staff had adopted a plan of action calling on them always to take the initiative. When their forces were strong, they would attack, but when they were tired and weak they would withdraw to their rear bases to rest, recuperate and regroup.”

Ky lit another cigarette. “Someday I will put all of this into a book,” he said. Ky did just that, publishing “How We Lost the Vietnam War” in 2002 some 27 years after we shared those “33 Bieres” in his Saigon compound.

The gist of that book was less of a condemnation of the American military, which acquitted itself well on Vietnam’s battlefields, than a disparagement of Washington’s insistence on applying Occidental solutions to Oriental problems. In essence, the book argues that America cannot project its values, beliefs, and customs on an alien culture and expect success.

In 1980, sitting in Ky’s house in Westminster, California, our conversation seemed to pick up where it left off in 1975.

“To insist that Vietnam fights a war while at the same time building democracy was impractical,” Ky said. “Building democracy in the West, in England and then in the United States, took centuries of struggle. We Vietnamese could only begin to build democracy after achieving peace and independence. And even then, democracy could not be achieved overnight but must be constructed in stages and harmony with the cultural, social and economic traditions of each people. To accuse South Vietnam of not establishing a democratic regime and to use that as an excuse for abandoning South Vietnam was a blatant betrayal of a trusting ally that had put all his faith in the word of America.”

Ky added that the White House and the Pentagon directly conducted the war from thousands of miles away, issuing contradicting policies with ever- changing directives that created confusion in commanders at the front.”

“The B-52 carpet bombings ordered by President Nixon toward the end came too late and were too short-lived,” he said. “They served only to pressure the Communists to come to the Paris peace talks so that America could prepare for an honorable withdrawal from Vietnam.

“After Watergate, America was a ship without a rudder,” he continued. “Vietnam was left to its own devices, drifting along towards its fate. The disintegration of April 1975 was an unavoidable conclusion. My only regret and sorrow is that the ending was shameful and tragic.”

Amen and rest in peace Nguyen Cao Ky.