Hundreds, if not thousands, of authors of fiction and non-fiction books, were once journalists. I am one of them. I spent 28 years as a national and foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. I consider it the best training ground for my entry into writing Historical Fiction, which my Finding Billy Battles trilogy is.

However, the leap from journalism to fiction is not always an easy one. Sure, journalists have learned the fundamentals of communicating via the written word. They understand description, pacing, transition, even character development, but most appreciate that those critical elements of writing are a bit different when it comes to producing fiction.

It is a pleasure today to share this blog post from Marylee MacDonald, who is not only an excellent writer but a wonderful teacher and mentor for aspiring authors. Please enjoy this excellent essay on the differences between journalism and fiction.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

For Writers Ready to Publish, For Writers Who Need Readers

By Marylee MacDonald,

What’s the difference between journalism and fiction, and why should you care? Well, if you’re a writer in this day and age, you’re likely to do more than one kind of writing. Long-form journalism often pays. Fiction rarely does. Or, at least, it can take time for people to find you and buy your books. That’s why fiction writers today pen articles for online magazines.

Some magazines expect you to write for free. Others pay for your guest post. The pay is good, but there’s another reason you might want to think about going back and forth between fiction and journalism. An insightful essay can boost a writer’s visibility. It can drive readers to your blog, and wouldn’t it be amazing if your essay went viral? In this post, I’m going to discuss the differences between the two kinds of writing.

Journalism vs. Fiction

Let’s start with a quick compare-and-contrast of the two forms.

| Journalism | Fiction and Creative Nonfiction |

| Focus on a single story | Multiple, interwoven stories |

| Begins with a “lede” summarizing the most important aspects of the story | The ends of paragraphs or scenes are where you’ll find summary information. |

| Objective-reportorial, with a voice that strives to remove the reporter’s “take on things” from that story | Subjective-attempt to render the subjective quality of an experience |

| Quotes to corroborate facts or present two sides of an issue | Dialogue used to place the reader in the scene, not for presenting alternate viewpoints or arguments |

| Voice-journalistic, “how-to,” factual | Voice-quirky, individualistic |

| Outside the head-can only write about what the reporter observes | Inside the thoughts; unique to fiction and some forms of subjective journalism such as the so-called “gonzo journalism” of Hunter Thompson |

| Facts must be verifiable with more than one source | Writers free to invent, even when writing about real people, such as T.C. Boyle’s novel about Frank Lloyd Wright, The Women. Rather than sticking with the facts, Boyle combined women, knowing he’d have a better story. |

| Claim to fact-based “truth.” | No claim to truth; unreliable narrators; exaggeration |

| Editorial viewpoint—opinion pages based on reasoned argument; logic | No soapboxes allowed |

| Linear, logical, and told in chronological time sequence | Okay to jump around in time, start and stop the story, or tell from different points-of-view |

| All narration apart from quotes from multiple sources | Stories are told in scenes and summaries. In scenes, the story slows down, and readers can judge for themselves based on observing characters’ behavior. |

| Sentences are written to newspaper’s style sheet and literacy level of readership; brevity; lack of subordinate clauses. | Sentences must advance the plot, provide imagery, reveal character, and provide back-story. Complex sentences don’t have to target readers with a 10th-grade reading level. |

Journalism and Its Uses

Here’s when you might want to think journalistically:

- When presenting newsworthy information (scientific breakthroughs or archaeological discoveries)

- When writing about historical events (perfect for writers of historical fiction)

- When pitching a guest blog to a national, online newspaper

- When you have multiple sources whose perspectives enlighten and inform

- When you want to get paid for your writing

- When writing a newsy press release

- When providing copy for a local paper featuring your book

Sites that welcome the kinds of articles fiction writers would be likely to write include Slate, Salon, The Atlantic, Vox, New Republic, The American Prospect, Mother Jones, The Daily Beast, FiveThirtyEight, Grantland, Medium, Aeon Magazine, and Huffington Post. If they like your idea, make sure they’ll link to your blog.

Why Should You Explore Opportunities in Journalism?

Let me state the obvious. Writing a novel takes quite a while. If you can begin developing a following by writing articles for online magazines, that will help you develop a platform and get your name out there. At the Pima Writers’ Conference two years ago, agent Michael Carr (of Veritas Literary in San Francisco) told me that he sits up and notices when a writer has published in Slate or Salon. (For more on agents and publishing, read this article.)

Many journalists write fiction. One of them is Ronald E. Yates, a former foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune and Dean Emeritus of the College of Media at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana. Here’s a blog post about how he used his skills as a journalist when writing historical fiction. His Finding Billy Battles Trilogy is an example of how he fused the skills of journalism with those of a writer of fiction.

While I’ve known many journalists who’ve made the leap into fiction, I know only a couple of fiction writers who’ve gone in the other direction. In case you decide to try your hand at nonfiction, here are a couple of things you should know.

Stylesheets for Journalism

One of the main differences between journalism and fiction/creative nonfiction may seem trivial to those who’ve never gone through an editorial vetting of your words. Journalists typically use the AP Stylebook, updated yearly and available online. For a quick overview, take a look at this page from the Purdue Online Writing Lab.

In contrast, literary writing takes its cues from the Chicago Manual of Style, otherwise known as CMOS. I like the online version because of its search capability.

If you’re into the fine points of writing, take a look at the stylesheet used by The Kansas City Star. Hemingway wrote police and emergency-room articles for the Star and commented that the stylesheet provided “the best rules I ever learned in the business of writing.”

Straight Journalism

In straight journalism, you must check your facts and confirm them with input from multiple, credible sources. Your sources must be willing to “go on the record,” meaning allow you to quote them. If they demur, then you’d better have other sources that can confirm. Such are the ethics of journalism: straight journalism. Your name will be mud, and you will never get a job at a reputable paper if you fail to adhere to these guidelines.

Not everyone does. Rick Bragg and Jayson Blair were two New York Times’ reporters who bit the dust after they filed false stories. These two writers alleged that they were reporting factual information. More recently, three members of a CNN investigative team were let go when the network discovered they’d only used a single source and had not “followed procedures.”

Subjective Journalism

Hunter Thompson, on the other hand, spent much of his life reporting stories, but they were stories in which he was personally involved. To get a sense of his style and viewpoint, read this article from The Paris Review.

Similarly, two other Western writers, Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner moved back and forth between writing fiction and writing for magazines. Here’s Abbey’s essay “Cowburnt,” published in Harper’s.

Wallace Stegner–Stanford professor, author of Angle of Repose, a novel, and Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, a biography of John Wesley Powell, the one-armed former general who was the first to risk a watery ride through the Grand Canyon–used the power of the pen to advocate for environmental causes. Here’s one of Stegner’s essays: “The Sense of Place.”

In my spreadsheet above, I noted that fiction is not the place to advocate for a cause. That’s why Stegner leaped from fiction to journalism. He wanted to “say his piece” about preserving Western lands.

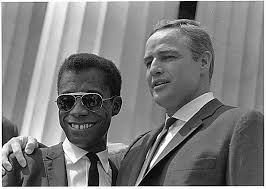

James Baldwin, of course, wrote amazing essays about race, culture, and the craft of writing. However, in his fiction, such as the emotionally evocative Another Country, he allowed the characters to live their lives. Readers could draw their own conclusions. For many years, Baldwin lived as an ex-pat in Paris. He came home to see his family and friends and write about race, culture, and politics. One of his best-known books was THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF MALCOLM X.

More recently, Roxane Gay, feminist and culture critic, has swung back and forth between fiction and essays. Like Stegner, she, too, teaches Creative Writing.

In Sum

Each kind of writing has pros and cons. For me, fiction is all about placing the reader in a situation and letting the reader experience how to stand in that character’s shoes and live the character’s life. It’s a way to try to get at a truth even I may not be able to explain fully.

And journalism? The kind of journalism I did for many years falls into the category of “how-to” writing. That training comes in handy when I’m writing blog posts.

Possibly, I’m a little afraid of the effort it would take to pitch one of the magazines above. I’d need sources. I’d need to fact-check. It would take time.

I actually have an essay on my hard drive. Maybe I should give it a second look.

Marylee MacDonald grew up in Redwood City, California, married her high school sweetheart, and worked as a carpenter in California and Illinois. When she’s not writing, she’s hiking in the red rocks of Sedona, walking on a California beach, or plucking snails from her tomatoes. Her short stories have won the Jeanne Leiby Chapbook Award, the Barry Hannah Prize, the Ron Rash Award, the Matt Clark Prize, and the American Literary Review Fiction Award. Here is a link to her website: https://maryleemacdonald.com/

So, where are YOU in all of this?

Do you have journalistic skills that might come in handy?

Are you an author with a background in journalism?

Let me know via a comment or two.

The list of “news” sites that welcome fiction writers is telling. I guess one could make a case that modern 21st-century journalism is more creative than the journalism with which I grew up. Fiction writers must feel right at home in today’s media.

The blurring between journalism (as I learned and practiced it) and opinion is telling today. Too many journalists feel entitled to inflict their opinions and ideologies on readers and rationalize that practice by telling themselves they are doing it for the “greater good.” Think about how the legacy media are refusing to examine the “woke” garbage of fraudulent and Marxist Critical Race Theory. In the meantime, millions of vulnerable K-12 children are being indoctrinated with this crap under the flimsy guise of history instruction.