[This is a re-post of a post I published a while back. I am posting it again because of questions I have received asking me to discuss how authors can use the skills practiced in professional journalism]

Without a doubt, one of the best places to learn the craft of writing is in the professional newsroom.

The number of successful authors of fiction and non-fiction books, who began their careers as journalists, is remarkable. Here is a list of 10 (It could be 50 or 100):

- Charles Dickens

- Samuel Clements (Mark Twain)

- Ken Follett

- Thomas Thompson

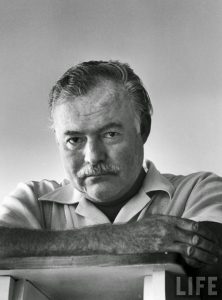

- Ernest Hemingway

- Edna Buchanan

- George Orwell

- Graham Greene

- PG Wodehouse

- Tom Wolfe

Someone once asked Ernest Hemingway where he learned to write. His answer: working as a general assignment reporter for the Kansas City Star from 1917 to 1918.

“Everything I needed to know about writing I learned from the Kansas City Star style sheet,” Hemingway once said.

The first paragraph of that stylesheet reflects Hemingway’s writing style. It begins: “Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative.”

The advice may seem simplistic, but it is far from it. One of the first things I learned as a young journalist (coincidentally, at the Kansas City Star) was how to write succinctly and clearly and how to gather information accurately.

Hemingway did all of those things–and he did them well, both as a journalist and later as a Nobel Prize-winning novelist.

Not far behind those skills is something called Journalistic Method. That is a fancy phrase for how a journalist works.

That is what I want to talk about today. In parts 2 and 3 of my blog on Journalistic Method, I will get into some of the other skill sets such as the aforementioned ability to write succinctly and clearly, how to gather information accurately, and how to organize it and present it compellingly. Those who write novels can learn a lot from the skills required to produce excellent journalism.

Journalism is an empirical discipline. What do I mean by that?

It means, like science, it is a search for truth. It means you use trial and error, observation and analysis to find the truth.

The Dictionary defines empiricism it this way: Relying on or derived from observation or experiment: empirical results that supported the hypothesis. b. Verifiable or provable by means of observation or experiment: empirical laws. Guided by practical experience and not theory.

It’s also how journalists go about finding stories.

For the scientist, empiricism means arriving at a truth via observation and experimentation. For the journalist, the empirical tools are: Observation and Interviewing.

The best writers, whether they are journalists, novelists or authors of non-fiction books, are the best observers.

Observation is the basis of everything.

Take this story from Asia about a Buddhist sage walking with two students through the forest. He stops suddenly and looks up at a tree.

“What do you observe in the tree?” He asks the first student. The first student’s eyes lock on the tree. Suddenly his face lights up.

“I see a bird in the tree, master,” he says, sure his powers of observation in finding the small bird in the tree’s thick green foliage will please his religious teacher.

“What do you see?” the aged priest asks the other student.

The second student pauses, his eyes fixed on the tree for several moments.

Finally, the second student speaks: “I see a bird with red, yellow and black feathers sitting on a dead limb. A green tree snake is crawling on a limb just behind the bird.”

That is observation. Observation is an active, not a passive process.

Legend has it that the ancient Druids forced candidates for the priesthood to study an oak tree and capture its every feature. Then the candidate would be questioned about the tree. If the candidate failed to describe the tree accurately, he would be nailed to it.

Druidic discipline is not practiced in newsrooms, but the precision of observation it was intended to encourage should. Not every good reporter is a good writer, but every good writer is a good reporter. Reporting IS observation.

Of the qualities that distinguish good from poor writing, three depend directly on observation. They are clarity, precision, and appeal to the senses. The others—pacing and transition—lend grace and power to the expression of what you have observed.

Clarity, precision, and appeal to the senses seldom are achieved just by looking or listening. You usually have to seek out information that is not readily apparent.

The reporter’s primary research tool is interviewing. All reporters interview; but few interview as well as they might. Fewer still get beyond the interview to other sources of information and understanding.

Documents, the records of business, government and personal life, can be invaluable in answering questions and providing detail. Even the methods of social science offer help for the writer who would be a better observer.

A keen observer understands the importance of detail and texture, as well as the use of precise language. That means fewer adjectives, but heavy on action verbs—fueled by detailed observation.

My advice: To write well, first see well.

Good observation depends on two things: concentration and analysis. As a writer, you must be an observer by occupation. That means you’re always on the job. Everything you see, hear, smell, taste, and touch is potentially material you can use in a story.

Flies take off backward. So to swat one, you must strike slightly behind it. That’s a detail a writer should be able to see. Other people see flies; a writer sees how they move.

No two people, no two situations, no two oak trees are identical. Your job is to sort out the essential differences. You must get in the habit of concentrating on what is going on around you. It is hard work. How do you do it?

- Look for the significant detail.

- Look for the revealing anecdote.

- Look with your mind, as well as your eyes, open.

- Prepare before you start to look.

Henry James once said: “Be one on whom nothing is lost.”

Listen to people talk. Listen to what they say and how they say it. Most of us don’t listen. Most of us are busy thinking about what WE want to say while someone else is talking. As a result, we misunderstand, misinterpret and worse, misquote.

Note things that others take for granted. For example, the excessive neatness of a bureaucrat’s desk may reveal not efficiency, but the fact that he or she has nothing to do! A pretentious private library may contain books with uncut pages!

So what’s the difference between a novelist and a reporter? Besides the fact that one writes fiction and the other doesn’t (or shouldn’t), their goals are similar: to create compelling stories that people will want to read, learn from or be entertained by.

You must describe! You cannot rely on imagination to give you the crusty feel of crisp frozen ground underfoot or the razor-drag of chill air across your face. You must see these things; know them, before you can communicate them.

Writers are verbal creatures. But they must observe vividly. Good writers write after the fact, not from inspiration. They write what they have seen—and what they have seen well!

[TOMORROW: PART 2]