This week I am focusing on memoirs–or more accurately, what they are and how to write them. I have written about this in the past and today and tomorrow I am going to share two posts on the topic that I wrote a while back. Then, on the third day, I will share a splendid post on memoirs written by a fellow award-winning author, Marylee MacDonald. If you are like millions of others who are thinking of writing a memoir, I hope you will take a look at these posts. They contain valuable insight and some excellent advice.

In my last post, I talked broadly about what a memoir is and what it isn’t. Now I want to focus on the fundamentals of writing that you need to master to produce a compelling memoir.

Some people think writing is nothing more than stringing together a collection of words that sound good in a sentence. That’s like a novice painter slapping a lot of different colors on a canvas because they look good together.

In both cases, the creation lacks focus and doesn’t tell a story.

The writer and the artist both need to understand and use the fundamentals of their disciplines to create something that stirs our emotions and satisfies us in some personal way.

People who write memoirs without understanding the most basic tenets of the writer’s craft are like the untrained and nascent artist who wants to paint like Monet or Degas without basic conceptual knowledge of composition, accent, and perspective; or how to properly employ the color wheel, the palette, and brushes.

There are only a couple of ways to learn those fundamentals. (1) Take some classes where your work receives evaluation and assessment from a credible, experienced professional; or (2) spend several months reading books and articles on writing and then practice, practice, practice by writing, writing, writing.

As Ernest Hemingway once said: “It’s none of their business that you have to learn how to write. Let them think you were born that way.”

The first thing you will learn when you sit down in front of your computer (or before that blank sheet of paper, if you decide to compose in longhand) is that writing is an intensely solitary activity. My advice is to seek support from other writers as you work on your memoir. Few people can appreciate the struggles a writer faces like another writer can.

I already mentioned that you should consider taking a writing course at a university, community college, or community center. Classes like these provide structure and often require you to produce a set number of pages on deadline. This kind of rigid structure is very helpful for some writers. It teaches writing discipline. The critical thing is this: the grades you receive (if grades are given) are less important than the skills you must master and the feedback you will receive.

You might also join a book club. Seek out an organization that specializes in memoirs and biographies, etc. Listen to what other readers admire in the books you are reading as well as what they don’t like. This information can prove invaluable to you when writing your memoir.

Join an online writers group. They are easy to find, and most cost nothing to join. Some are more serious than others, but in most cases members are eager to share information about such things as the writing process, research, submitting a manuscript for publication, sending work to literary agents, etc.

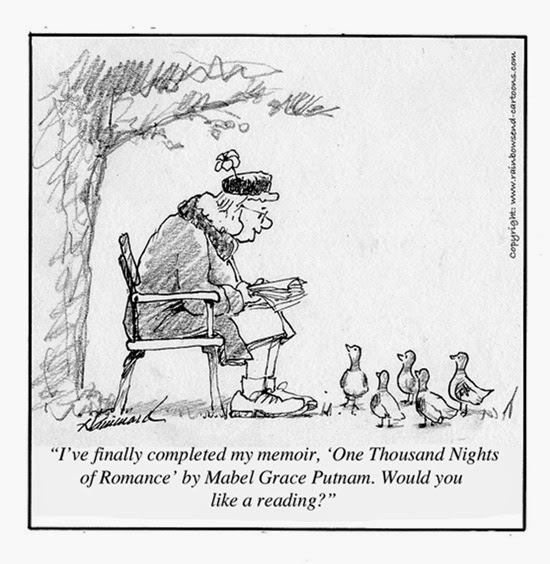

Make a point of attending book festivals and local readings at libraries and book stores. You should join in the world of books and write at the grassroots level. Talk to other authors and listen to their experiences, not only in writing but in marketing their books. You will develop new friendships, learn new lessons, and come to see and appreciate books in a new light.

Now, let’s look a few fundamentals of memoir writing.

Perhaps the first thing you need to ask yourself is: Why are you writing a memoir? Is it to leave a legacy for your family or others? Is it to share what you have learned in your life; your wisdom? How will others feel after reading your memoir? Will they be happy or touched? Will what you write make a difference in their lives? And how will you feel after you finish your memoir? Will you be fulfilled, pleased or will you feel there are still some things left unsaid?

Don’t be too hard on yourself. But at the same time, be truthful. Writing a memoir is as much about telling the truth about your life, as it is recording important events. You are not going to remember some things you wish you could, and you will remember some things you wish you could forget. That’s life! It is filled with success and anguish. It is those experiences–both good and bad– that make an excellent memoir.

Memory is volatile. You may remember peculiar details, such as the smell of one of your grandmother’s favorite dishes, but forget your grandmother’s first name. Not to worry. The answers may come in dreams, chance conversations, photos or letters.

There will be times when you won’t know what to write. Don’t let that stop you. Write down anything that is in your head. You may feel what you are writing sounds stupid. That’s OK, write it down anyway. It doesn’t matter. The key is to keep writing, typing the words in your computer or keeping the pen moving over the paper. Eventually, the words will begin to flow.

Isaac Asimov may have said it best: “Writing, to me, is simply thinking through my fingers.”

Think about writing a little each day. Don’t worry if the task seems daunting or that you don’t appear to be producing very much. Think about it. It took you years to live your life and deal with the experiences you have had. You can’t write it all down in a few short days or weeks. Take it one day at a time. In a few weeks or months, you will have produced dozens of pages.

In writing a memoir remember that emotional truth is often more important than factual truth. What do I mean by that? What years did Uncle Bill serve in the Army? What was the unforgettable neighbor’s name who lived across the street? These are all significant details that you will want to know when writing your memoir. But don’t worry if you can’t recall them.

More important is how proud you were when your brother was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor or how relieved you were when your car wouldn’t start at 3 am on a stormy night, and a neighbor drove you and your pregnant wife to the hospital and got you there five minutes before your daughter was born.

Facts fill in the story’s canvas. But it’s the emotive truths that hold the story’s heart.

Don’t tell your story sequentially. That’s too obvious. Most good books don’t start at the beginning. Instead, they captivate you with instant conflict and intrigue. A good beginning provides readers with just enough deception to hook them without revealing the ending. Then it returns to the chronological beginning and fills in the backdrop.

When you’re writing, make sure you use all five of your senses. You want your readers to inhabit vivid new worlds that you have created for them. However, too many novice writers produce first drafts that are lackluster, mind-numbing and uninspiring.

Write colorfully, intensely, and with texture, if you want to transport readers to the world you are creating. How do you do that? By creating detail; by using all of your senses (sight, smell, touch, sound, and taste) to re-create a moment in time fully. It’s easy to learn how to do this. The next time you’re waiting in a line at a restaurant, the post office or the dentist’s office, become aware of the different sights, sounds, smells, and textures around you.

That’s what good writers do. They observe, they listen, they feel, and they incorporate those sensations in their stories.

As Stephen King says: “Description begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s.”

Ultimately, your work must withstand the judgment of the reading public. That can be a harsh, frightening and disquieting experience for some.

“A person who publishes a book willfully appears before the populace with his pants down,” Edna St. Vincent Millay once wrote.

The fact is, some people will like what you write; others will not.

I am reminded of the English professor who once wrote to a student: “I am returning this otherwise good typing paper to you because someone has printed gibberish all over it and put your name at the top.”

Of course, as Sinclair Lewis said: “It is impossible to discourage the real writers — they don’t give a damn what you say, they’re going to write.”

That may be the most appropriate attitude for any writer to cultivate.

Tomorrow: Writing a Memoir: Five Common Misconceptions