Today, I am posting a Q & A with pollsters Arie Kapteyn of USC’s Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research and Robert Cahaly of the Trafalgar Group. In 2016 both men foresaw a Trump victory, while other pollsters were predicting a Clinton landslide. They say in 2020 most polls are once again undercounting Trump’s support.

The Q & A was conducted by Zack Stanton of Politico Magazine. Take a look. I think you will find it fascinating. Zack Stanton is digital editor of Politico Magazine.

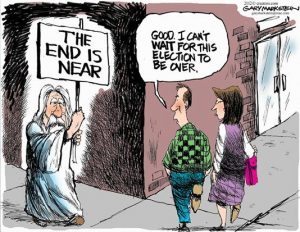

With Nov. 3 racing toward us, it can be tempting to see the 2020 election as a done deal. For months, Joe Biden has consistently and convincingly led Donald Trump in polls. Swing states in the industrial Midwest and Sun Belt appear to be heading Biden’s way, and if you trust the polls, it’s not a leap to imagine him winning 330+ electoral votes.

But what if you shouldn’t trust the polls?

In 2016, months of national polls confidently showed Hillary Clinton ahead, and set many Americans up for a shock on Election Night, when the Electoral College tilted decisively in Trump’s favor. Two pollsters who weren’t blindsided by this are Arie Kapteyn and Robert Cahaly. Kapteyn, a Dutch economist who leads the USC’s Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research, oversaw the USC/Los Angeles Times poll that gave Trump a 3-point lead heading into election day—which, Kapteyn notes, was wrong: Clinton won the popular vote by 2 points. Cahaly, a Republican pollster with the Trafalgar Group, had preelection surveys that showed Trump nudging out Clinton in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Florida and North Carolina—all of which he won.

This year, both men believe that polls could again be undercounting Trump’s support. The reason is “shy” Trump voters—people reluctant to share their opinions for fear of being judged. Though the “shy voter” idea is thrown around a lot by both Trump supporters and Democratic skeptics, Kapteyn and Cahaly have specific insights into why, and how, Trump support might be going undetected.

For Cahaly, those votes are likely to make the difference again. “There’s a lot of hidden Trump votes out there,” he says. “Will Biden win the popular vote? Probably. I’m not even debating that. But I think Trump is likely to have an Electoral College victory.”

As an illustration, Kapteyn described what his team at USC sees in its polls. Beyond simply asking voters whether they support Biden or Trump, USC asks a “social-circle” question—“Who do you think your friends and neighbors will vote for?”—which some researchers believe makes it easier for people to share their true opinions without fear of being judged for their views.

“We actually get a 10-point lead, nationally, for Biden over Trump” when asking voters who they personally plan to support, says Kapteyn. “But if you look at the ‘social-circle’ question, Biden only gets like a 5- or 6-point lead. … In general—and certainly on the phone—people may still be a little hesitant to say to that they’re Trump voters.”

“We live in a country where people will lie to their accountant, they’ll lie to their doctor, they’ll lie to their priest,” says Cahaly. “And we’re supposed to believe they shed all of that when they get on the telephone with a stranger?”

This year, conventional pollsters say they’ve learned their lessons, and are accounting for factors that skewed their results last year. Kapteyn and Cahaly aren’t so sure, as they explained to POLITICO this week via Zoom. A transcript of that conversation is below, condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Election Day is next week. National polling averages show Biden leading Trump by around 9 points. In 2016, averages had Clinton up by around 3 points, but you both ran polls that showed Trump winning the presidency. What do you see this year?

Robert Cahaly, the Trafalgar Group: Well first, we don’t do national polls, and that’s for the same reason I don’t keep up with hits in a baseball game: It’s an irrelevant statistic. But the battleground-state polls are a little closer [than the national polls], and there’s a lot at play. People are going to be shocked. A lot of people are going to vote this year who have been dormant or low-propensity voters. I think it’s going to be at an all-time high.

The models of who’s going to turn out this year are very flawed. What type of person comes out for Trump? They’re not a normal election participant. They’re a low-propensity voter. We included them in all of our surveys in fall 2016, and we are including them now.

Relying on live callers for polls is especially bad in this modern era, where “social desirability bias” is in full play. People avoid awkward conversations. So when a person you don’t know calls and asks how you feel about Donald Trump—and you don’t know how they feel—you tend to give them an answer that you think will make them look at you in the best light. We’ve seen it year after year, and I think it is very much at play this year.

Polls are undercounting the people who don’t want to give their real opinions. If they had corrected anything, why didn’t they see Ron DeSantis winning in his 2018 race for governor in Florida? They made the exact same mistake with his opponent, Andrew Gillum. [The final RealClearPolitics polling average in that race had Gillum up by 3.6 percentage points. DeSantis won by 0.4 percentage points.] This wasn’t some random state’s race; this was the hottest, meanest—neck-and-neck races for governor and senator in Florida in an off-year election. Every single major player was polling that state. And 100 percent of them got it wrong; we got it right.

Arie Kapteyn, USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research: First, let me start with a qualification about our results four years ago. It looked as if we did a good job because our national poll had Trump winning. But that, of course, was wrong: In the popular vote, Trump actually lost. So we didn’t do that well, and the reason why was our sample had an overrepresentation of people in rural states. Even though we weighted by education and past voting participation and all of that, we simply had too many Trump voters in the sample.

We have about 9,000 people in our panel [this year], and they answer questions every two weeks. And we ask them a number of things. We ask the probability that they will vote. We ask them the probability they’ll vote for Biden or Trump or someone else. But we now also ask them a question I think you’d always asked, Robert: “Who do you think your friends and neighbors will vote for?” We call it a “social-circle” question.

Now, we actually get a 10-point lead, nationally, for Biden over Trump. But if you look at the “social-circle” question, Biden only gets like a 5- or 6-point lead. One explanation for that may indeed be “social desirability.” In general—and certainly on the phone—people may still be a little hesitant to say to that they’re Trump voters.

Cahaly: I have many problems with polling today. It’s outdated. Part of it is they can’t concede that this model of long questionnaires, small sample sizes and exclusively live callers—I mean, they’re attacking the guys putting up telegraph wires, but they’re running the Pony Express.

People are busier than ever, and long questionnaires reduce the ability of average people to participate. Who has time to answer 22 questions on a Tuesday night when you’re trying to fix dinner or put your children to bed? Nobody. You end up with people on the ideological extremes—either very conservative or very liberal—or, worse: people who are bored.

We give [respondents] lots of different ways to participate—online, by text or email. You get one of our text polls at 7 p.m., and you can flip through it while watching TV, or answer Question 1 at 9 p.m. and answer Question 2 the next morning. That’s fine! We give you the time to participate on your schedule. We make it very easy. It takes less than three minutes if you do it all at once.

Kapteyn: We have an Internet panel, but it’s a little different from most others. We recruit our respondents by sending them letters. We buy addresses from the post office—or from a vendor—draw randomly from addresses in the United States, invite people to participate in our studies and we pay them really well. We pay them join, and then $20 for a 30-minute interview. We have a relationship of trust with them.

I agree that telephone polling in the traditional way, as far as I can tell, is pretty close to death. You get extremely low response rates, and there is this issue: Who is still answering the phone?

That’s a thing [our surveys] don’t really suffer from as much, because these people typically answer questions that aren’t about politics. We ask them about their health or their finances. We give them cognitive tests. We do all sorts of scientific work. We get them to wear accelerometers and we measure their physical activity. Because they participate in all of this, they’re probably less likely to be extreme—although if they had no interest in politics, they might not participate.

You both spoke with POLITICO after the 2016 election. Back then, you said that one of the big things polling missed was “shy” Trump voters. In retrospect, do you still think that’s the case, or was there something else at play?

Kapteyn: We actually did a little experiment during the 2016 election: If you get called for a survey, and a live person asks who you’re going to vote for, do you answer that question differently than if you’d received the question in a letter and mailed it back, or answered the survey online?

We found some evidence that being called up by someone you don’t know makes people more hesitant to reveal their voting preference. And if you looked at whether these were Trump or Clinton voters, you did see that those people who told us they were Trump supporters were more likely to say they would not share their preference if they got called on the phone. So that at least suggests that there was a “shy Trump voter” phenomenon in 2016. Whether that’s the case this year, I really have absolutely no idea. We haven’t looked at that, and I just don’t know.

Cahaly: I believe it was prevalent. In 2016, the worst being said about Trump voters is that they were “deplorable.” 2020 is a whole different ballgame. It is worse this time—significantly worse. This year had more things where you can get punished for expressing an opinion outside the mainstream than almost any year I can think of in modern history.

I’m finding that people are very hesitant [to share their preference for Trump], because now it’s not just being called “deplorable.” It’s people getting beat up for wearing the wrong hat, people getting harassed for having a sticker on their car. People just do not want to say anything.

We talk to lots of people in our surveys. And I hear things like, “Yeah, I’m for Trump, my neighbors are for Trump, but there’s one neighbor who just hates Trump. And when he walks his dog, he kind of wrinkles his nose by those houses, and I don’t want him to do it at my house, so I don’t put a Trump sign. I like the guy, and I don’t want him mad at me.” I hear stuff like that all the time. People are playing their cards close to their chest because there’s a stigma to being for Trump. What happens when the stigma rolls away from people who hide their vote, and they start admitting where they are? This is what I think is going to happen on Election Day.

Now, there’s certain people who are vocal Trump supporters. To me, it has more to do with your personality. Are you the kind of person who avoids awkward conversations, or are you the kind of person who enjoys them? If you enjoy them, and you’re for Trump, you’ll tell everybody. You’ll be in a boat parade! But if you’re the kind of person who’s quiet and non-confrontational, you aren’t going to say anything. And a lot of those people live in the Midwest. They’re very regular, down-to-earth folks who are kind and deferential.

Robert, I’m from the Midwest—Macomb County, Michigan, the home of the “Reagan Democrats,” which voted for Obama twice then flipped to Trump. When you go there, you see tons of Trump flags in people’s yards or waving from their trucks, reading, “Trump 2020: No More Bullshit.” It’s difficult for me to believe that people who are not shy about expressing their support for Trump in pretty much every other instance are shy when—

Cahaly: But they’re different people! Think about what you just said, because that’s the reason why other Trump supporters are shy: The soccer mom doesn’t want to say she’s for Trump because she doesn’t want you to think she’s one of them. You just made my point for me! That’s exactly it! [Laughs]

This is probably a horrible example, but there are a lot more people who like professional wrestling than admit it. There are lots of fans who don’t want you to think they’re like the other people who like professional wrestling.

Kapteyn: The only point I would make is that it seems that over the years, increasingly, political preferences are localized. One county, one area is safe Democratic; the other area is Republican. If you’re in the minority—you’re a Democrat in a Republican area, or a Republican in a Democratic area—civil political discussions have sort of ceased to exist. People become careful in expressing their political preference if they feel that their whole neighborhood has a different opinion.

In that sense, I think there will be some symmetry in shyness, at least in sort of day-to-day conversations. It’s not the same as answering the phone to someone you have never talked to, but there is a lot of evidence that suggests people are careful expressing their opinions if they feel they are in the minority.

Cahaly: Absolutely true. It doesn’t matter whether it’s in a family or a company, people do not like talking about politics when they feel like their opinion is in the minority.

Robert, after the 2016 election, you told POLITICO that you didn’t buy the idea that there were shy Clinton voters.

Cahaly: I don’t.

Do you believe there are shy Biden voters?

Cahaly: No. And not because it’s just for Republicans. For example, had Bernie Sanders been the nominee and been beat up every day as being socialist, there would be a tremendous “shy” vote among moderate-to-conservative Democrats who would vote for him as their nominee, but who may not want to tell people.

It depends on the polarization of the figure. Nobody looks at Joe Biden and says, “Oh, it’s toxic to be for him. People say Biden supporters are pond scum.” Nobody says that. Nobody does that. It’s really about the stigma you get for supporting the person.

Kapteyn: This is why I feel that using the Internet [for surveys]—in the way we do it—may help us a little bit. If someone on the Internet checks the box for Trump, no one is going to yell at them.

If someone is shy about their views, how do you measure that? You mentioned using online surveys rather than live phone calls. But how do you actually measure the existence of a group of people who won’t give you their opinions? How do you know they exist?

Kapteyn: Partly, you ask, “What do your neighbors think?” or “What your friends think?” That’s an indirect way of eliciting opinions.

Generally, if you do surveys, people give you all sort of wrong answers. In cases where you can verify it, you’ll find that there are very systematic biases. For example, one of the things we do at USC is we measure people’s physical activity—how active they are, how often they do sports. And I’ve done international comparative work on this. If you ask about it, Americans are just as active as the Dutch or the English. But if you measure it—

Cahaly: [Laughter] I love it.

Kapteyn: —you get a Fitbit, and sure enough, you notice an enormous difference. This is not unique to political polling; there is a general issue with asking questions and what to do with the answers.

Cahaly: I couldn’t agree more. We live in a country where people will lie to their accountant, they’ll lie to their doctor, they’ll lie to their priest. And we’re supposed to believe they shed all of that when they get on the telephone with a stranger and become Honest Abe? I cannot accept that.

Now, how we measure it is a little different. We find questions that are less confrontational. We brought the “neighbor” question into the mainstream, but I got that from a man named Rod Shealy, who’s since passed. I learned a lot from him doing politics in South Carolina. He always said that people are real polite, so when you need to know what they think about something that’s not pleasant to talk about, ask them what their neighbors think, because they’ll give you their real opinion without you judging them for it.

This year, we’re asking a series of other questions that are easy and don’t seem like you’re going to get judged harshly for answering them. Our first goal is to minimize the social desirability effect. And you do that by giving them a great sense of anonymity. The more anonymous they think they are when giving answers, the more honest they tend to be.

It’s kind of like the people who have two Twitter accounts—the one where they tweet out pictures of their pets and children, and one where they just go give everybody a fit. Well, that “troll” account is their real emotion. And the persona that runs that troll account is the one in the ballot booth. That’s who I’m trying to get to.

The results in 2016 really hurt people’s willingness to trust polls. You’re seeing it now: Democrats say, “Biden is leading, but the polls showed Clinton winning in 2016, and she lost.” Among Republicans, it’s sort of the opposite: “The polls in 2016 didn’t reflect Trump’s strength, but he won and will win again.” So how should people look at the polls over the final days of this campaign?

Cahaly: One, they should ask themselves these questions: Do you know someone who is going to vote for Trump—someone who maybe confided that fact in a few people, but didn’t share it widely? Do you think that person, if called on the phone by a stranger—a live person who knows who they are—would tell them? If the answer is yes, then you should be skeptical of polls that are given with a live person.

And ask yourself, would you answer a survey that took 20 or 25 minutes on a Tuesday night when you’re feeding your family? If the answer is no, then you should look with skepticism at polls with long questionnaires.

Kapteyn: I think it’s good to add some nuance to the idea that polls didn’t do so well in 2016, because after all, if you look at the national polls, they actually weren’t very far off when it came to the popular vote.

Another thing that may be a little underappreciated: One of the things that was quite clear just from looking at the data is that there were events late in the election season in 2016 that had an effect—for example, [FBI Director James] Comey’s announcement that he was reopening the investigation of Hillary Clinton’s emails. That moved the needle by, like, 2 percentage points or so. I could see that in the data. And that’s a big number, given how tight the election was. So I think there were some reasons why the polls seemed worse than they perhaps were—and why they couldn’t be more accurate, because some major events happened very late.

Cahaly: I’m a little different on that one, because we saw the Trump numbers the whole time. Nothing was new about them to us.

Did the gap between polling in 2016 and the results affect the way either of you think about polling?

Cahaly: I became fascinated with why there was denial that social desirability bias was in play and important. It made me realize just how critical the assurance of anonymity is to getting an honest answer.

Other people started using our “neighbor” question, as Arie pointed out. And that caused us to think of some new questions we thought would be more revealing. And this time, we decided we weren’t going to share them with the world.

Kapteyn: In that sense, we are at opposite ends of the spectrum. We [USC’s Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research] are not a polling firm; we’re a research firm. We happen to have this Internet panel where we ask people all sorts of questions, so why not also ask them about politics? For us, this is largely an experiment. That’s why we ask about this in different way: We want to see what works best.

Frankly, if I were in the business of trying to forecast who’s going to be elected, then a national poll is a pretty poor instrument for doing that, because it has become increasingly clear that the battleground states are really what matter. As far as I can tell, there are many more state polls than four years ago—for good reason. You see them in all the battleground states.

My model is more this: Try to understand what works, get into these social desirability or other questions as, frankly, a scientific exercise. And then, in the process, I will be happy if my estimate is right on the mark. But if it isn’t, we have probably learned something, too.

Last question: The election ends on Tuesday. National polling has consistently shown a substantial lead for Biden. What is your message to people who think that this thing is done?

Cahaly: I don’t think it’s done. Some of these national polls are not even taking into consideration the fact that Republicans have closed the gap with voter registrations. I don’t think they’re taking into account the number of low-propensity voters who are voting and who will vote on Election Day. I don’t think they’re measuring people’s genuine opinions. And I think [pollsters] are just not going to see it coming.

There’s a lot of hidden Trump votes out there. Will Biden win the popular vote? Probably. I’m not even debating that. But I think Trump is likely to have an Electoral College victory.

Kapteyn: I will be really surprised, given our own numbers, if there isn’t a very sizable gap between Biden and Trump in the popular vote—in favor of Biden. But in the states? I don’t know.

Cahaly: I like your skepticism.