This is a re-post of a story I posted in 2019 about legendary Chicago Daily News foreign correspondent Keyes Beech, one of the most respected and ethical journalists I have ever known. If you didn’t see this the first time around, I encourage you to take a look now. You won’t be disappointed.

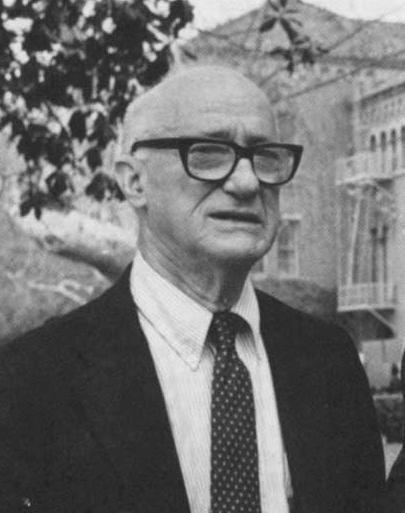

Keyes Beech, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1951 for his Korean War battlefield coverage, was based in Hong Kong when he wrote the essay below for The Chicago Daily News centennial edition in 1976. A renowned correspondent for The Chicago Daily News Foreign Service until it was closed in 1977, Beech died at age 76 in 1990.

Keyes Beech was a wonderful role model for any newly-minted foreign correspondent, which is what I was in 1974 when I was sent to Tokyo as the Chicago Tribune’s Far East Correspondent. We crossed paths often in places like Bangkok, Saigon, Taipei, Manila, and Hong Kong, where Keyes lived for many years. Like me, he was in Saigon on April 29, 1975, when the city fell to Communist North Vietnamese troops; and like me, it was not an even that he was proud of.

And even though he worked for a competing newspaper I never really saw him as a competitor–just a fellow foreign correspondent doing the best he could to keep his readers informed. Keyes was not a great raconteur. In fact, he was a pretty quiet guy who let his writing do his talking. And his writing was exemplary and had a lot to say.

I recall after the Chicago Daily News folded Keyes had just moved to San Diego. I was based in Los Angeles with my office in the Los Angeles Times building. One day a friend from the L.A. Times came to my office and told me the Times had just hired Beech. He would be going back to Asia–specifically, Bangkok.

When I asked Keyes about it he told me: “I was hanging up a picture when the phone rang and the Times offered me the job. I think I wavered about 30 seconds and then said yes.” He stayed in Bangkok until 1983, when he finally decided he had had enough.

Even though I was based in Los Angeles, my “beat” was all of Asia and Latin America–which meant I was traveling about 60 percent of the time. One week I might be in Singapore or Hong Kong and the next I could be in Mexico or Chile.

“Ridiculous,” Keyes told me one day when we were having lunch in Bangkok. “What the hell are the editors at the Tribune thinking?”

I didn’t have an answer. But in his essay below Keyes said what a lot of foreign correspondents think about when they look back on their careers of covering war and mayhem.

When asked what we have to show for years of slogging through jungles, racing for planes, running for cover, eating putrid food, and sleeping in fleapit hotels, many of us will answer as Keyes did in this 1977 essay.

‘Survival itself is no small achievement’

By Keyes Beech

HONG KONG — I went to the Far East for The Daily News for a year’s tour of duty.

That was nearly 30 years ago. And I’m still out here.

It has, with a few exceptions, been a happy relationship. I still hold a grudge against the bookkeepers for refusing to pay $25 for a pair of glasses I broke on a Chinese Nationalist ship while dodging a piano that had gone berserk in turbulent seas in the Formosa Strait in 1958.

On a loftier plane, I can still work myself into a towering rage at my editors’ refusal to allow me to go into Communist China in 1957 when Peking had granted me a visa. I finally got back in — 18 years later.

I’ve always said that if I ever lost my capacity for indignation, I would get out of this business. The difference is that today I am more selective in what I get angry about. Which means, I suppose, that I am older, sadder and, I hope, wiser.

I didn’t really mean to stay in Asia so long, but things kept happening and I kept staying on because I wanted to be where the action was.

Of course, there were all those wars. I’m sensitive about covering so many wars: Some of my friends have suggested that I’m a warmonger. I should like to point out that I didn’t start those wars. I merely reported them. On my 25th anniversary in Asia, I was having dinner with a friend in Bangkok. He asked me, only half-jokingly, what I had to show for all those years.

“Well,” I said defiantly, “I survived.”

That in itself is no small achievement for anyone who has spent nearly 30 years of his life in this part of the world, racing for airplanes, jumping out of helicopters, dodging bullets now and then, sometimes wondering if your next step was going to come down on a land mine.

When I stop to think about it, more of my friends are dead than alive. And a shocking number of them died violent deaths in Korea and Vietnam. Yet during all those years, I have never been seriously ill. And the only injury I suffered during the better part of a decade in Vietnam was breaking a heel bone while hanging a curtain in my house in Saigon.

I wonder who’s living there now?

A staggering amount of history has been written since I arrived in Tokyo in May 1947. I was not long out of the Marine Corps as a combat correspondent and a rather cocky reporter who was soon to be humbled by how much he did not know and how much he would never know about the “mysterious Orient.”

I watched people starve in Shanghai and Peking as the Communist armies tightened their grip on the cities and the weary Nationalists disintegrated under the weight of their own corruption and incompetence.

I escaped from Seoul by the skin of my teeth in 1950 as the North Koreans rolled in. I watched the Japanese rebound from defeat to become the world’s third greatest economic power. I watched the newly independent countries of Southeast Asia grope for a form of government that would suit their needs.

In the process, I learned two things that should have been obvious to begin with. One was that there is no Asia, only Asians. “What do I have in common with an Indonesian?” a Japanese cabinet minister said coolly.

The answer was nothing, except that they both belong to the human race.

The other thing I learned was that democracy is at best a fragile export when transplanted to Asian soil. The only democracy left in Asia today is Japan, which alone among Asian nations had the machinery to make it work.

Over the years, I have seen the American stature in Asia steadily diminish. We emerged from World War II bright and shiny and noble — or so it seemed to many Americans and a great many Asians.

But time and attrition have damaged that image beyond repair. The myth of American omnipotence was shattered in the rice paddies of Vietnam.

Perhaps it was inevitable. Perhaps it was even healthy. But for one who remembers those heady days when Americans thought they could do anything, it takes a little getting used to.

One of the proudest moments of my life was the day in 1960 when hundreds of thousands of South Koreans cheered the American flag as the corrupt, tyrannical Syngman Rhee regime came to an end.

The saddest and most shameful day was April 29, 1975, when I left the American embassy roof in Saigon by helicopter as thousands of frightened Vietnamese clawed at the embassy gates. It was not a nice way to go.

“… still hold a grudge against the bookkeepers for refusing to pay $25 for a pair of glasses I broke on a Chinese Nationalist ship while dodging a piano that had gone berserk in turbulent seas in the Formosa Strait in 1958.”—His next accounting should have had a note for the bookkeeper, “Find the glasses.” because they were surely in there somewhere.

Going to war with the people in the green eyeshades is often a losing battle for us hacks. I know from whence Beech speaks.