Given the explosion of antisemitism in the United States and much of the world today, I thought I would re-run the following post that I published on ForeignCorrespondent in 2019. I think it has significant relevance in today’s political climate. I hope you find it as interesting as I did. Please read on.

I ran across this story not long ago and put it aside until I could do some of my own reporting. It tells of how Ernst Leitz II who headed E. Leitz, Inc., designer and manufacturer of the Leica Camera, Germany’s most famous photographic product, defied the Nazi’s and saved scores of German Jews. As with most of the public, I wasn’t aware of the story. Now, I am pleased to share it.

The Leica was the first globally popular 35mm camera. It’s a German product – precise, minimalist, and utterly efficient. Behind its worldwide acceptance as a creative tool was a family-owned, socially oriented firm that, during the Nazi era, acted with uncommon grace, generosity, and modesty. E. Leitz Inc., designer, and manufacturer of Germany’s most famous photographic product saved its Jews.

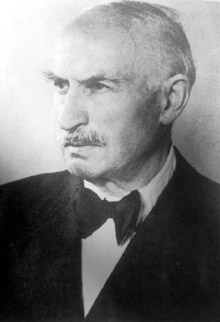

And Ernst Leitz II, the steely-eyed Protestant patriarch who headed the closely held firm as the Holocaust loomed across Europe, acted in such a way as to earn the title, “the photography industry’s Schindler.”

As soon as Adolf Hitler was named chancellor of Germany in 1933, Ernst Leitz II began receiving frantic calls from Jewish associates, asking for his help in getting them and their families out of the country. As Christians, Leitz and his family were immune to Nazi Germany’s Nuremberg laws, which restricted the movement of Jews and limited their professional activities.

To help his Jewish workers and colleagues, Leitz quietly established what has become known among historians of the Holocaust as “the Leica Freedom Train,” a covert means of allowing Jews to leave Germany in the guise of Leitz employees being assigned overseas.

Employees, retailers, family members, even friends of family members were “assigned” to Leitz sales offices in France, Britain, Hong Kong, and the United States, Leitz’s activities intensified after the Kristallnacht of November 1938, during which synagogues and Jewish shops were burned across Germany.

Before long, German “employees” were disembarking from the ocean liner Bremen at a New York pier and making their way to the Manhattan office of Leitz Inc., where executives quickly found them jobs in the photographic industry Each new arrival had around his or her neck the symbol of freedom – a new Leica camera. The company paid the refugees a stipend until they could find work. Out of this migration came designers, repair technicians, salespeople, marketers, and writers for the photographic press.

Keeping the story quiet The “Leica Freedom Train” was at its height in 1938 and early 1939, delivering groups of refugees to New York every few weeks. Then, with the invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, Germany closed its borders. By that time, hundreds of endangered Jews had escaped to America, thanks to the Leitzes’ efforts.

How did Ernst Leitz II and his staff get away with it? Leitz, Inc. was an internationally recognized brand that reflected credit on the newly resurgent Reich. The company produced cameras, rangefinders, and other optical systems for the German military. Also, the Nazi government desperately needed hard currency from abroad, and Leitz’s single biggest market for optical goods was the United States.

Even so, members of the Leitz family and firm suffered for their good works. The Gestapo jailed a top Leitz executive for working to help Jews and freed him only after the payment of a large bribe.

Leitz’s daughter, Elsie Kuhn-Leitz, was imprisoned by the Gestapo after she was caught at the border, helping Jewish women cross into Switzerland. She eventually was freed but endured rough treatment in the course of questioning. She also fell under suspicion when she attempted to improve the living conditions of 700 to 800 Ukrainian slave laborers, all of them women, who had been assigned to work in the plant during the 1940s. (After the war, Kuhn-Leitz received numerous honors for her humanitarian efforts, among them the Officier d’honneur des Palms Academic from France in 1965 and the Aristide Briand Medal from the European Academy in the 1970s.)

Why has no one told this story until now? According to the late Norman Lipton, a freelance writer, and editor, the Leitz family wanted no publicity for its heroic efforts. Only after the last member of the Leitz family was dead did the “Leica Freedom Train” finally come to light.

Several years ago Frank Dabba Smith, a California-born Rabbi living in England penned a book about the Leitz family’s efforts entitled: “The Greatest Invention of the Leitz Family: The Leica Freedom Train.”

After World War II Leitz refused to talk about his efforts on behalf of his Jewish workers, and the story remained unknown for decades.

As the late radio commentator Paul Harvey used to say: “Now you know the rest of the story.”

For filing under “No Good Deed Goes Unpunished”—In 1988, 32 years after Leitz’s death, Holocaust survivors filed a legal suit against the Leica company for employing slave labour during the war. Leica settled by paying into a compensation fund. Thank you, Ron, for the interesting and evocative article.

I guess it comes down to a matter of perspective. Schindler used slave labor also, but I don’t think he was sued. May Leica didn’t save enough Jews to offset those who were left behind.