Ocassionally, I post stories I wrote while working as a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. I filed the story that follows in Febrary 1987 after returning from a foray into Afghanistan with a warlord and his Mujahideen militia. The Mujahideen, who eventually morphed into the Taliban, were fighting the Russians who had invaded Aftghanistan in 1979. I was impressed by the incredible toughness of the men I was with. They were rugged, seemingly fearless, and incredibly dedicated to expelling the Russians from a country known as the “graveyard of empires.”

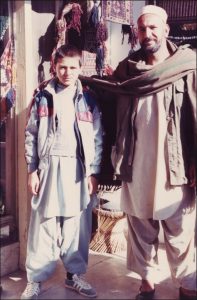

But what astonished me, even more, were the boys, some as young as 10, who were also fighting alongside the men. The story I filed is about one of those boys–a 12-year-old named Daoud Bahrami. It’s a story that never left me and when American troops invaded Afghanistan in 2001 in an effort to wipe out Al Qaeda and their Taliban supporters, I recall thinking: “Man, our troops are going to meet men who were once boys like Daoud–kids who were tough and committed and ready to make the supreme sacrifice. This is not going to be easy.”

And, as we now know, it wasn’t easy. In fact, after 20 years we are leaving without achieving anything close to a victory. Yes, we obliterated Al Qaeda and inflicted tremendous damage on the Taliban, but in the end, we lost–just as we did 47 years ago after a 10-year-long war in Vietnam in another land populated mostly by simple peasant farmers.

I hope you will read this story about Daoud Bahrami. It contains some stark lessons about Afghanistan and why that nation has earned the sobriquet “graveyard of empires.”

Feb 8, 1987

The Khyber Pass, Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan–Twelve-year-old Daoud Bahrami can’t remember exactly when he stopped being a child.

It might have been a year ago when he attached a magnetized time bomb to a Soviet truck in a convoy parked on the outskirts of Kabul and barely reached safety before it and the men inside were shredded by the explosion.

It could have been while running messages for the anti-Soviet Mujahideen (Holy Warriors) down the narrow, twisting streets of Kandahar with Soviet soldiers firing their Kalashnikov rifles at him.

Or it may have been that day 18 months ago when he woke up and discovered there just wasn’t time to be a child in a country being ripped apart by war.

In that respect Daoud is a lot like an estimated 1 million other Afghan children, half of them orphans, growing up in one of 314 refugee camps scattered along the Pakistani frontier while the seven-year-old war in Afghanistan rages.

But unlike most of his youthful peers, Daoud has not spent much time languishing in a camp for displaced persons. He is a child who has been trained to kill, who looks at you coolly, severely, with an unsettling lack of passion.

There was no way to corroborate his story, although adult guerrilla fighters said children frequently are used on such missions. Daoud’s own matter-of-fact manner added to his credibility. How many men, for instance, has he killed?

“Maybe one, maybe 10,” he says simply, speaking through an interpreter while sitting on the floor of the small Afghan carpet shop his family operates in Islamabad.

In most cases, Daoud never stayed around long enough to find out the extent of the carnage he created. His job was to use his size to creep as close as he could to unsuspecting Soviet troops, trucks, and tanks, throw his antitank bomb or hand grenade, and dash for cover.

That’s exactly what he did on his last assignment for the fundamentalist Jamiat-e-Islami, one of seven Mujahideen guerrilla groups trying to drive out the Soviet army.

As the sun was dropping behind the low hills that flank the edge of Afghanistan’s capital in mid-December, Daoud was handed an antitank weapon and a hand grenade by his commander and told to work his way close enough to several Soviet T-54s to “do some damage to the infidels.”

Daoud had done this before, so he knew just how close he would have to get to the “big brown iron beasts.”

“I tied the bomb here with my belt,” he said, pointing to the small of his back. “And then I crawled along the rooftops of maybe 15 buildings until I was looking down on the Russians and their tanks. I could see them laughing and trying to make friends with the Afghan people.

“Some of the Russian soldiers were trying to sell parts of their uniforms, like their belts and hats to the people so they could get money. The Russians are always trying to get money by selling something.

“There were three tanks and they were sitting still. I watched for about two minutes to make sure there were no more tanks or soldiers and I leaned over the edge of the roof and dropped my bomb into an open turret hatch. Then, I threw my hand grenade at a group of soldiers standing nearby.”

Daoud fled over the rooftops. After running about 20 yards, he was jolted off his feet by an earth-shattering eruption as the powerful antitank bomb ripped through the innards of the T-54. That was followed by another explosion as the hand grenade unleashed its lethal spray of shrapnel.

“I could hear the soldiers screaming and crying,” Daoud recalled. “Then they began shooting at the rooftops and into the houses with their Kalashnikovs. They were scared.”

Was Daoud afraid? Only that he would fail.

“I am not afraid to die,” he said. “In my heart, I would like to be a shaheed (martyr). So death does not frighten me. I welcome it.”

Daoud’s father, sitting on the floor nearby, beamed approvingly.

“If he goes to war and comes home alive, I will be happy,” he said, looking proudly at his son. “And if he goes to war and is martyred, I will be just as happy.”

Daoud’s brother, Hamad, 15, is more pragmatic about the war that has mutilated Afghanistan and its 15 million people since 1979 when 110,000 Soviet troops invaded. He wants to finish the school he and Daoud attend for Afghan refugees just across the border in Pakistan. He doesn’t want to go back to Afghanistan and the fighting–something he did for almost three years until he turned 15 a few months ago.

“When I think of my future these days I think of myself as a businessman, not as a soldier,” Hamad said.

“You are wrong, Hamad, you should be in the army and help drive the infidel Russians out of our land,” Daoud said, looking sternly at his brother.

“Everybody serves Allah in his own way,” said the boys’ father, rubbing his stubby beard. “If just one of my sons goes to the jihad (holy war) and is martyred, perhaps that is enough.”

Ameena, the boys’ mother, who was filling our small porcelain cups with freshly-brewed tea, shook her head.

“I do not want my sons to be martyred,” she said, her voice unwavering and resolute. “I want them to be free to live in peace.”

Daoud regarded his mother for a moment. “You must fight and make sacrifices to get those things,” he said.” And sometimes you must die.”

“Allah yuafiquna,” she muttered as she walked out of the room, shaking her head.

I looked at Daoud’s father. He translated:

“My wife said: ‘Allah help us.'”

But Daoud had the last word.

“Allah will not help us. We must help ourselves or live as slaves.”

Thank you, Ron, for your timely reposting of material to help readers understand the dynamics of current events unfolding as we read. I have only one minor quibble: “The Mujahideen, who eventually morphed into the Taliban, …” — This is accurate in the narrow sense that the Taliban eliminated the other factions of the Muj, especially the Hazaras. The Taliban was the Pashtun faction, which used its majority status to seize control when the other factions fell into internecine squabbling.

You are correct, James. I could have been more specific about the Mujahideen-Taliban transition, but I figured it might take too long to explain the infighting of Mujahideen factions and the dominant Pashtun faction which emerged as the strongest group. I wanted to keep the focus on Daoud. In any case, thanks for the clarification. You do know your stuff regarding the “graveyard of empires.”

Ron, Thank you for your gracious response, as well as your excellent article. Three years on the wrong end of the Khyber were not totally wasted, Baradar.

👍