Our society seems obsessed with labels. Take the word “Hero,” for example. It is applied in the most absurd and inappropriate ways to people who don’t deserve that distinction.

When Whitney Houston died in 2012, for example, I couldn’t believe people were calling her a “hero.”

Why? Because she was a wonderfully talented singer who eventually threw her life and career away with a deadly addiction to different drugs such crystal meth, marijuana, cocaine, and pills such as Xanax, Flexeril, and Benadryl?

How exactly does that make her a “hero?” It doesn’t. It doesn’t even make her a good role model.

And what about others who have been accorded the “hero” appellation?

Remember US Airways Capt. Chesley Sullenberger, who in 2009 landed his plane full of passengers on New York’s Hudson River after his engines conked out? Sullenberger was quickly labeled “hero”–a term he says is not appropriate.

“That didn’t quite fit my situation, which was thrust upon me suddenly,” he said. “Certainly, my crew and I were up to the task. But I’m not sure it quite crosses the threshold of heroism. I think the idea of a hero is important. But sometimes in our culture, we overuse the word, and by overusing it, we diminish it.”

The Pittsburgh-based Carnegie Hero Fund Commission defines a hero as “someone who voluntarily leaves a point of safety to assume life risk to save or attempt to save the life of another.”

“When the engines stopped on US Airways Flight 1549 in January 2009,” Commission president, Mark Laskow wrote, “Capt. Sullenberger was not in a place of safety. On the contrary, he was in the same peril as the passengers whose lives he saved with his piloting skill. He did not have the opportunity to make a moral choice to take on the risk — it ‘was thrust upon him. I do not doubt that if he did have such a choice, he would not have hesitated to place himself in danger to save his passengers. That just wasn’t the actual situation in which he found himself.”

Once upon a time, I served in the U.S. Army. I did my job and did it pretty well as my various awards, and eventual promotion to Sergeant attests. But I was no “hero.” I volunteered, I did my job, and I left with an honorable discharge. When a soldier, marine, airman or sailor puts on his or her uniform, they are just doing their jobs.

Today, we apply the word “hero” to all servicemen and women who serve in the armed forces. How often do we hear people refer to “our heroes in Afghanistan?” They are not heroes. They are servicemen and women, and they are doing their duty serving their nation. When they are injured, wounded, or even killed they are casualties, but not necessarily heroes.

A hero is a person who goes above and beyond the call of duty and puts him or herself in harm’s way to perform an act of selfless gallantry. You might argue that servicemen and women put themselves in harm’s way on a daily basis, but that is their job–and they volunteered for that job. So how does that make “ALL” servicemen and women “heroes?”

It doesn’t.

I sometimes wear a baseball cap when I go shopping. On the front, it identifies me as a U.S. Army Veteran–a fact that I am very proud of. Sometimes people see that and thank me for my service. When that happens, I often feel a bit awkward. Yes, I did serve four years on active duty and another four in the reserves. But I don’t feel anybody owes me a “thank you.” I volunteered for the U. S. Army, and I did the job I was assigned to do. I am certainly no “hero” because of it.

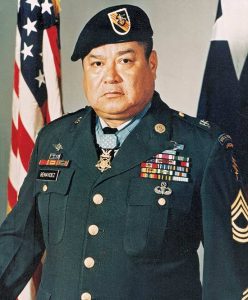

Do you want to know what a hero is? Here is a hero. His name was Roy P. Benavidez. Not long ago someone sent me an e-mail that contained the fantastic story of his life.

In 1965 Benavidez was sent to South Vietnam as a Green Beret advisor to an ARVN infantry regiment. He stepped on a landmine during a patrol and was evacuated to the United States, where doctors at Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC) concluded he would never walk again and began preparing his medical discharge papers.

But Benavidez, who was known by the radio call sign as “Tango Mike Mike” (“That Mean Mexican”) was not ready to accept that diagnosis.

Against doctors’ orders, he began an unsanctioned nightly training ritual in an attempt to redevelop his ability to walk. Climbing out of bed at night, Benavidez would crawl using his elbows and chin to a wall near his bedside and (with the encouragement of his fellow patients, many of whom were permanently paralyzed or missing limbs), he would prop himself against the wall and attempt to lift himself up unaided.

After several months of excruciating practice that by his own admission often left him in tears, he was able to push himself up the wall with his ankles and legs. After more than a year of hospitalization, Benavidez walked out of the hospital in July 1966, with his wife at his side, determined to return to combat in Vietnam.

Benavidez returned to Fort Bragg to begin training for the elite Studies and Observations Group (SOG). Despite continuing pain from his wounds, he became a member of the 5th Special Forces Group and returned to South Vietnam in January 1968.

That’s when this man’s incredible story of heroism began. This is what his Medal of Honor Citation says:

“On the morning of 2 May 1968, a 12-man Special Forces Reconnaissance Team was inserted by helicopters in a dense jungle area west of Loc Ninh, Vietnam to gather intelligence information about confirmed large-scale enemy activity. This area was controlled and routinely patrolled by the North Vietnamese Army. After a short period of time on the ground, the team met heavy enemy resistance and requested emergency extraction.

“Three helicopters attempted extraction but were unable to land due to intense enemy small arms and anti-aircraft fire. Sergeant Benavidez was at the Forward Operating Base in Loc Ninh monitoring the operation by radio when these helicopters returned to off-load wounded crewmembers and to assess aircraft damage.

“Sergeant Benavidez voluntarily boarded a returning aircraft to assist in another extraction attempt. Realizing that all the team members were either dead or wounded and unable to move to the pickup zone, he directed the aircraft to a nearby clearing where he jumped from the hovering helicopter and ran approximately 75 meters under withering small arms fire to the crippled team.

“When he reached the leader’s body, Sergeant Benavidez was severely wounded by small arms fire in the abdomen and grenade fragments in his back. At nearly the same moment, the aircraft pilot was mortally wounded, and his helicopter crashed. Although in extremely critical condition due to his multiple wounds, Sergeant Benavidez secured the classified documents and made his way back to the wreckage, where he aided the wounded out of the overturned aircraft and gathered the stunned survivors into a defensive perimeter.

“Prior to reaching the team’s position he was wounded in his right leg, face, and head. Despite these painful injuries, he took charge, repositioning the team members and directing their fire to facilitate the landing of an extraction aircraft, and the loading of wounded and dead team members. He then threw smoke canisters to direct the aircraft to the team’s position. Despite his severe wounds and under intense enemy fire, he carried and dragged half of the wounded team members to the awaiting aircraft. He then provided protective fire by running alongside the aircraft as it moved to pick up the remaining team members. As the enemy’s fire intensified, he hurried to recover the body and classified documents on the dead team leader.

“Under increasing enemy automatic weapons and grenade fire, he moved around the perimeter distributing water and ammunition to his weary men, re-instilling in them a will to live and fight. Facing a buildup of enemy opposition with a beleaguered team, Sergeant Benavidez mustered his strength, began calling in tactical air strikes and directed the fire from supporting gunships to suppress the enemy’s fire and so permit another extraction attempt.

“He was wounded again in his thigh by small arms fire while administering first aid to a wounded team member just before another extraction helicopter was able to land. His indomitable spirit kept him going as he began to ferry his comrades to the craft. On his second trip with the wounded, he was clubbed from behind by an enemy soldier. In the ensuing hand-to-hand combat, he sustained additional wounds to his head and arms before killing his adversary. “

He then continued under devastating fire to carry the wounded to the helicopter. Upon reaching the aircraft, he spotted and killed two enemy soldiers who were rushing the craft from an angle that prevented the aircraft door gunner from firing upon them. With little strength remaining, he made one last trip to the perimeter to ensure that all classified material had been collected or destroyed, and to bring in the remaining wounded. Only then, in extremely serious condition from numerous wounds and loss of blood, did he allow himself to be pulled into the extraction aircraft.

“Sergeant Benavidez’ gallant choice to join voluntarily his comrades who were in critical straits, to expose himself constantly to withering enemy fire, and his refusal to be stopped despite numerous severe wounds, saved the lives of at least eight men. His fearless personal leadership, tenacious devotion to duty, and extremely valorous actions in the face of overwhelming odds were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him and the United States Army.”

The citation stops short of telling what happened when the helicopter reached its base. Benavidez was put into a body bag, and as it was being zipped up, using what little strength he had left, he spits on the face of the medic to show he wasn’t dead.

Roy Benavidez died on November 29, 1998, at the age of 63 at Brooke Army Medical Center, after suffering respiratory failure and complications of diabetes. He was buried with full military honors at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery.

Now THAT is the definition of a HERO!

For those who want to see and hear more about Master Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez, you can do so by clicking on the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZ7968BbMnU&feature=player_embedded