(I continue to receive requests that I repost my piece on Evelyn Waugh’s “Scoop,” the classic book that lampoons foreign correspondents. I first read Scoop in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in March 1975 as Communist Khmer Rouge guerillas surrounded the besieged city. Day after day, the Khmer Rouge bombarded the city with 107mm Chinese-made rockets that battered refugee camps, hospitals, and hotels–a harsh foreboding of the genocide millions of Cambodian people would suffer at the hands of the Khmer Rouge.

Of course, at the time, the relative handful of us journalists ensconced at the old Le Phnom Hotel had no way of knowing just how brutal the Khmer Rouge would be when they marched into Phnom Penh. We were preoccupied with the daily struggle to get our dispatches out via clunky old telex machines and unreliable telephones when the electricity was turned on–which wasn’t often. Here is my piece on Waugh’s “Scoop,”–the hilarious and biting satire of foreign correspondents in the mid-1930s. Enjoy.)

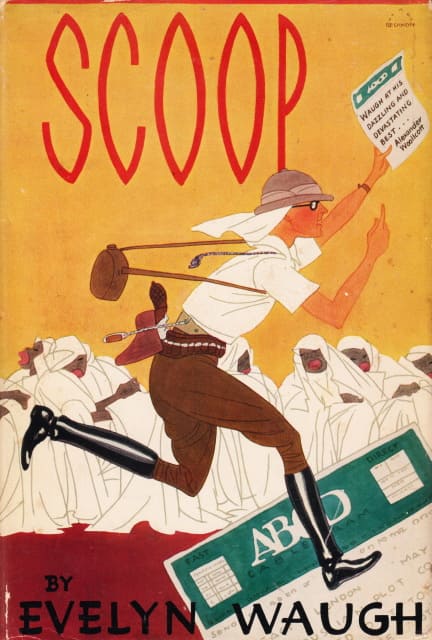

If you have never read Evelyn Waugh’s excellent satire of British journalism entitled “Scoop,” get thee to Amazon or a bookstore and buy the book. You won’t be disappointed.

“Scoop” ranks number 60 of the 100 best novels. For a good reason.

It’s fast, funny, and wonderfully written. In an era of online journalism, blogs, and social media, it still has an undeniable ring of relevance and truth about it, even though it was published in 1938.

The book is based partly on Waugh’s own experiences as a green correspondent in Ethiopia, where he covered the Italian invasion of that country for the Daily Mail in 1935.

At its heart, Scoop is a story about mistaken identity. A timid and hapless nature writer for London’s Daily Beast (Daily Mail) named William Boot, who writes a weekly column entitled “Lush Places,” is mistaken for John Boot, a distant cousin and novelist who wants to be sent to Africa to cover an impending war.

The powers at the Beast get the two Boots mixed up and erroneously dispatch William Boot to the fictional East African country of Ishmaelia, where he has no idea what he is doing or how to write anything beyond his nature column.

Indeed, William Boot’s idea of outstanding journalistic prose is, “Maternal rodents pilot their furry brood through the stubble” and “Feather-footed through the plashy fen passes the questing vole”—both lines from his Lush Places column.

Not to worry. Despite never knowing what exactly is happening around him and sending dispatches back in Latin to keep competitors from reading his copy, Boot manages to “scoop” the gaggle of famous (or infamous) correspondents who have come to write about a war between barefoot, spear-chucking natives, and the modern, highly mechanized Italian army.

The sub-title of Scoop is “A Novel About Journalists.”

However, it is more than that. Much more. The novel strips away the mystique of the foreign correspondent. It reveals many as self-serving egotists who would just as soon start a war as cover one and believe that the most important thing about any story is that they have arrived to cover it.

Not a very flattering picture. I say this as somebody who has covered war and mayhem in almost every continent of the planet.

Take this passage from Scoop about a legendary wire service foreign correspondent named Wenlock Jakes:

“Why, once Jakes went out to cover a revolution in one of the Balkan capitals. He overslept in his carriage, woke up at the wrong station, didn’t know any different, got out, went straight to a hotel, and cabled off a thousand-word story about barricades in the streets, flaming churches, machine guns answering the rattle of his typewriter as he wrote.

“Well, they were pretty surprised at his office, getting a story like that from the wrong country, but they trusted Jakes and splashed it in six national newspapers. That day every special in Europe got orders to rush to the new revolution. Everything seemed quiet enough, but it was as much their jobs were worth to say so, with Jakes filing a thousand words of blood and thunder a day. So they chimed in too. Government stocks dropped, financial panic, a state of emergency declared, army mobilized, famine, mutiny — and in less than a week, there was an honest to god revolution underway, just as Jakes had said. There’s the power of the press for you.

“They gave Jakes the Nobel Peace Prize for his harrowing descriptions of the carnage — but that was colour stuff.”

As Boot arrives in Ishmaelia, there is no war, which is not a problem for the invading hacks. They merely go about fabricating hostilities to please their editorial bosses back home. Boot is at a loss. How is it that he is missing all the action when few correspondents ever actually leave the bars in their hotels?

While Boot files tedious stories about the geography and anthropology of Ishmaelia, his competitors are sending dispatches rife with “blood and thunder.”

For example, Boot cables the following bit of twaddle to the Beast:

“Ishmaelia, that hitherto happy commonwealth, cannot conveniently be approached from any part of the world. It lies in the northeasterly quarter of Africa, giving colour by its position and shape to the metaphor often used of it: “the Heart of the Dark Continent.”

“Desert, forest, and swamp, frequented by furious nomads, protect its approaches from those more favoured regions which the statesmen of Berlin and Geneva have put to school under European masters. An inhospitable race of squireens cultivate the highlands and pass their days in the perfect leisure which those peoples alone enjoy who are untroubled by the speculative or artistic itch.”

Naturally, he incurs the wrath of Salter, the managing editor of the Daily Beast, because the Daily Brute and other Fleet Street competitors are clobbering the Beast daily. To top it all off, Salter is being verbally thrashed by Lord Copper, the publisher of the Beast, because of Boot’s dearth of rousing war reporting.

He receives several “rockets” (choleric cables) from his office, such as, “OPPOSITION SPLASHING FRONTWARD SPEEDIEST STOP ADEN REPORTED PREPARED WARWISE FLASH FACTS BEAST.”

However, the inexperienced Boot cannot decipher cablese and has no idea what the cable says.

Finally, Boot receives a cable from an exasperated Salter, saying, “LORD COPPER PERSONALLY REQUIRES VICTORIES!”

Another correspondent eventually explains to a disillusioned and confused Boot why they are all in Ishmaelia: “News is what a chap who doesn’t care much about anything wants to read. And it’s only news until he’s read it.”

That crisp line pretty sums up journalism as Waugh saw it.

In the end, William Boot, like Evelyn Waugh himself, survived the pitiless and harsh eccentricities that cutthroat newspaper journalism was once upon a time.

Many hacks didn’t.

Ron—Thank you for pointing out that “Scoop” was based on Waugh’s experiences in Ethiopia. I never realized that before reading your article. Having spent a few years of my youth in Ethiopia, I immediately bought “Scoop” based on my high trust in your recommendation.

I think you will enjoy Scoop, J.C.–especially with your experience in Ethiopia!