Those of us who write historical fiction are faced with a plethora of unique challenges. In fact, there are so many that it would be difficult to deal with all of them in one post.

So I will break the challenges down into several parts, which I will share with you over the next several blog posts. I hope you find these posts interesting, and if you do, PLEASE FEEL FREE TO COMMENT. I would love to know what you think.

This first post deals with one of the greatest challenges when it comes to writing historical fiction: How to balance historical accuracy with artistic license.

I spent 27 years of my life as a reporter and foreign correspondent with the Chicago Tribune. Working for a newspaper taught me some basic skills regarding reporting, which is the reporter’s word for research. Journalism is an empirical discipline. That means, like science, it is a search for truth, and, like science, you use trial and error, observation and analysis to uncover that truth.

For the scientist or scholar, or historian, empiricism means arriving at truth via observation and experimentation. For the journalist, the empirical tools are Observation and Interviewing. I believe any successful journalist, author, or scholar must master both of those skills–along with the ability to respect the language and to write evocatively.

If you use the empirical tools of observation and interviewing correctly and skillfully, you will find that the information you are gathering is mostly accurate.

Accuracy when writing historical fiction is critical. That may sound like a paradox. It is not. A critical element in historical fiction is the way people communicate with one another. You want to make sure your characters, if they are in the 19th Century (as mine are when the Finding Billy Battles trilogy begins) are using the correct lingua franca.

You don’t want your protagonists and antagonists using 21st Century colloquial speech or slang in 1880s Kansas. For one thing, that destroys the sense of time and place, and for another, it reveals to the reader that the author has not researched the era enough or is too lazy to learn and employ the vernacular of the time. I see this mistake all the time, especially in American films that are set in earlier periods.

When a character in a book or film set in the 19th Century says something like: “This sucks,” or “Are you nuts?” or “Give me a break!” I am immediately turned off by the story. It happens all the time–maybe not as obviously as those examples, but you get what I mean. I am sure you have heard or read similar out-of-time and place comments.

In the 2016 remake of the film Ben-Hur, for example, during the climactic chariot race, Messala shouts at Judah Ben-Hur, “Are we having fun yet, brother?” I wager that phrase was never uttered by an ancient Roman. That kind of out-of-place comment is a distraction, an intrusion that demonstrates either a lack of knowledge of the time the story is set in or, even worse, no regard for the ear of the audience.

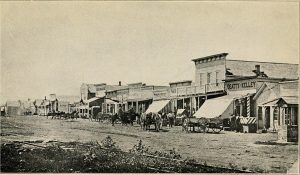

So that is a big issue for me. Another is in making sure places are accurately described. For example, in writing the first book of my Finding Billy Battles trilogy, I had to describe the Kansas towns of Lawrence and Dodge City as well as Denver, Colorado, as they looked in the 1880a and 1890s. I used the Kansas Historical Society to find old maps of Lawrence and Dodge City. I did the same with a historical group in describing Denver. I also had to describe the Wadsworth Old Soldiers Home in Leavenworth, Kansas, where Billy Battles first meets his great-grandson. In the book, the two sit on the veranda talking. In reality, as a student intern at the Kansas City Star in 1968, I actually interviewed a 98-year-old Spanish-American War veteran on the same veranda.

In The Improbable Journeys of Billy Battles (Book 2 of the trilogy), I had to describe what Honolulu, Yokohama, Hong Kong, Manila, and Saigon looked like between 1894 and 1899. Because I lived and worked in these locations during my time as a foreign correspondent, I already knew what they looked like from the 1970s to the present During the years I worked in Asia and Latin America, I made it a point to collect old maps and books about places like Saigon and Manila. I was always fascinated by what Asian cities looked like during their colonial periods, and I also knew that someday I would write a novel or two about them that was set in the 19th Century.

I think it is essential to establish historical credibility with readers. Once that is done, you can allow fiction to run rampant in your story. I believe readers are willing to suspend belief in things that a character does IF the author has accurately nailed an event’s time and place.

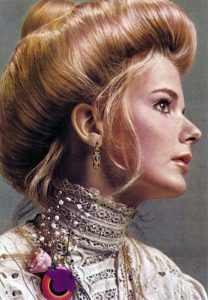

People, for the most part, behaved differently in the 1880s and 1890s. Having them do and say things that people do and say in 2022 is to ignore accuracy and precision. Relationships between men and women were very different (at least in public) in 1895 than they are today. Men–at least most men–demonstrated a particular deference toward women. It was simply the gentlemanly thing to do. Those who didn’t observe such conventions were regarded as cads, brutes, or beasts–to use the patois of the time.

Women did not wear pants in 1895–at least not on the streets of places like Denver, Lawrence, Kansas, or Manila. They did not carry handguns and shoot villains on sight–at least not frequently. In fact, most women who wanted to dispatch an abusive man did so with poison–at least, that is what my research of 19th Century crime records found–the legend of Lizzie Borden notwithstanding.

If you want your heroine or female antagonist to blow the brains out of a brutish man or to give him 40 whacks with an ax, you can certainly write it that way IF you have established historical accuracy and trust with your reader.

In my mind, that is how you balance accuracy and artistic license in historical fiction. The reader must believe that the time, the place, and the conduct of your characters are consistent with the era about which you are writing. Can your protagonist or antagonist act out of character within the epoch in which your book is set? Absolutely. But if they do, it is seen as an anomaly and not something the reader (or people alive at that time) would expect.

That is not a bad thing. It can give your story tension, and even texture. But you must use it sparingly because you don’t want it to become commonplace throughout the story.

Another area that is critical to good historical fiction is the way things smelled, the way things felt, and the way things sounded in the period about which you are writing. For example, in describing Dodge City, Kansas, when Billy Battles arrives there as an 18-year-old newspaper apprentice, I wanted to make sure the reader knew how the place smelled because of the thousands of Texas cattle in pens on the outskirts of town waiting to be loaded into boxcars for slaughterhouses in Kansas City and Chicago. Then there were the stinking buffalo hides that were piled 30 and 40 feet high south of the Arkansas River. Streets in those days were not paved and were usually littered with horse apples, garbage, stagnant water, and road kill.

Not a very pleasant sight–or smell.

Clothing in the 19th Century, especially women’s clothing, was often uncomfortable. Cloth was abrasive, irritating, and heavy; buildings were often unpainted and built from coarse wood. The food was not always fresh or prepared with the greatest attention to sanitation and safety. In Book 1 of my trilogy, Nellie Cashman (a real Irish woman who operated the Russ House Restaurant in Tombstone, Arizona) runs an ad in the Tombstone Epitaph that proclaims to her potential customers: “My kitchen is clean and free of cockroaches.” I found that ad while looking through old copies of the Epitaph.

All of these things, and I am sure I haven’t included everything here, must be considered when balancing accuracy with artistic license. For me, this is second nature. Paying attention to accuracy is what I did for a quarter century as a journalist. The artistic license didn’t come into play until recently when I began writing fiction–or what I like to call “FACTION.”

(Next: The Challenges of Writing Historical Fiction: Part Two)

[If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign up for notifications box on the right side of this post or at: https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent You can also find my commentaries on the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us. And please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!]