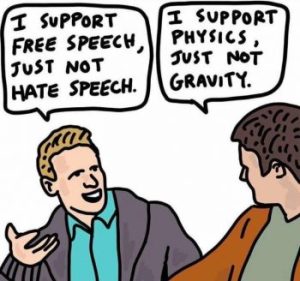

Let me say right off: I do not believe in the idea of hate speech. One person’s “hate speech” is another person’s “free speech.”

In that regard, the American Civil Liberties Union and I are in 100 percent agreement. More on the ACLU later.

In a previous post, I talked about Political Correctness in Historical Fiction novels. I argued that there can be no PC in a historical novel because if there is, the novel will be devoid of reality. PC is a 20th and 21st Century phenomenon. It didn’t exist in the 19th Century or any other prior century. So to purge a book set in the 18th or 19th Century of offensive expressions used in 18th or 19th Century America is to be dishonest.

A direct offshoot of PC is the concept of “Hate Speech.” Just as with PC there are unofficial Hate Speech police out there who like nothing more than to be the final arbiters of what can and cannot be said publicly in America.

Contrary to a common misconception, most expression one might identify as “hate speech” is protected by the First Amendment and cannot lawfully be censored, punished, or unduly burdened by the government — including public colleges and universities.

The Supreme Court of the United States has repeatedly rejected government attempts to prohibit or punish “hate speech.” Instead, the Court has come to identify within the First Amendment a broad guarantee of “freedom for the thought that we hate,” as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes described the concept in a 1929 dissent.

In a 2011 ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts described our national commitment to protecting “hate speech” in order to preserve a robust democratic dialogue: “Speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, and—as it did here—inflict great pain. On the facts before us, we cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker. As a Nation, we have chosen a different course—to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate.”

In other words, the First Amendment recognizes that the government cannot regulate “hate speech” without inevitably silencing the dissent and dialogue that democracy requires. Instead, we as citizens possess the power to most effectively answer hateful speech—whether through debate, protest, questioning, laughter, silence, or simply walking away.

To ban any speech is in complete opposition to an individual’s First Amendment right to speak freely and openly about any and all topics–be it race, gender, homosexuality, abortion, gay marriage, traditional marriage, war, or peace.

You may even criticize radical Islam–though, today, if you do, you are likely going to be accused of being a racist or Islamaphobe. That is when you will experience the PC Thought Police and their close relatives, the Hate Speech Gestapo, at their narrow-minded worst.

If you were to go back in time to 19th Century America or Europe, you might be appalled at the terms used openly and without remorse to describe blacks, Native Americans, Hispanics, the Irish, Italians, Catholics, Jews, Asians, etc.

That was life back then. Was it right to use those terms? Of course, today, we would say “No.” But using racial, ethnic, and religious slurs in the past was simply the way things were.

So if you are writing a historical novel about that period, do you eliminate dozens of objectionable terms and phrases to satisfy today’s PC Thought Police and the Hate Speech Gestapo?

The answer: an emphatic NO!

If you do clean up a novel about slavery and use words like “African-American” instead of the range of hurtful expressions commonly used in the 19th Century, your book will not only lack integrity; it will be a ridiculous fabrication.

Now back to the ACLU.

Rather than paraphrasing the ACLU’s position on Hate Speech, I will let that organization itself explain why it says there is no such thing as Hate Speech in a nation where speech is protected by the First Amendment of our Constitution.

The Q & A that follows is taken directly from the ACLU’s website.

Q: I just can’t understand why the ACLU defends free speech for racists, sexists, homophobes and other bigots. Why tolerate the promotion of intolerance?

A: Free speech rights are indivisible. Restricting the speech of one group or individual jeopardizes everyone’s rights because the same laws or regulations used to silence bigots can be used to silence you. Conversely, laws that defend free speech for bigots can be used to defend the rights of civil rights workers, anti-war protesters, lesbian and gay activists, and others fighting for justice. For example, in the 1949 case of Terminiello v. Chicago, the ACLU successfully defended an ex-Catholic priest who had delivered a racist and anti-Semitic speech. The precedent set in that case became the basis for the ACLU’s successful defense of civil rights demonstrators in the 1960s and ’70s.

The indivisibility principle was also illustrated in the case of Neo-Nazis, whose right to march in Skokie, Illinois, in 1979 was successfully defended by the ACLU. At the time, then ACLU Executive Director Aryeh Neier, whose relatives died in Hitler’s concentration camps during World War II, commented: “Keeping a few Nazis off the streets of Skokie will serve Jews poorly if it means that the freedoms to speak publish or assemble any place in the United States are thereby weakened.”

Q: I have the impression that the ACLU spends more time and money defending the rights of bigots than supporting the victims of bigotry!!??

A: Not so. Only a handful of the several thousand cases litigated by the national ACLU and its affiliates every year involve offensive speech. Most of the litigation, advocacy, and public education work we do preserves or advances the constitutional rights of ordinary people. But it’s important to understand that the fraction of our work that does involve people who’ve engaged in bigoted and hurtful speech is very important:

Defending First Amendment rights for the enemies of civil liberties and civil rights means defending it for you and me.

Q: Aren’t some kinds of communication not protected under the First Amendment, like “fighting words?”

A: The U.S. Supreme Court did rule in 1942, in a case called Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, that intimidating speech directed at a specific individual in a face-to-face confrontation amounts to “fighting words” and that the person engaging in such speech can be punished if “by their very utterance [the words] inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” Say a white student stops a black student on campus and utters a racial slur. In that one-on-one confrontation, which could easily come to blows, the offending student could be disciplined under the “fighting words” doctrine for racial harassment.

Over the past 50 years, however, the Court hasn’t found the “fighting words” doctrine applicable in any of the hate speech cases that have come before it since the incidents involved didn’t meet the narrow criteria stated above. Ignoring that history, the folks who advocate campus speech codes try to stretch the doctrine’s application to fit words or symbols that cause discomfort, offense, or emotional pain.

Q: What about nonverbal symbols, like swastikas and burning crosses — are they constitutionally protected?

A: Symbols of hate are constitutionally protected if they’re worn or displayed before a general audience in a public place — say, in a march or at a rally in a public park. But the First Amendment doesn’t protect the use of nonverbal symbols to encroach upon or desecrate private property, such as burning a cross on someone’s lawn or spray-painting a swastika on the wall of a synagogue or dorm.

Q: Aren’t speech codes on college campuses an effective way to combat bias against people of color, women, and gays?

A: Historically, defamation laws or codes have proven ineffective at best and counter-productive at worst. For one thing, depending on how they’re interpreted and enforced, they can actually work against the interests of the people they were ostensibly created to protect. Why? Because the ultimate power to decide what speech is offensive and to whom rests with the authorities — the government or a college administration –not with those who are the alleged victims of hate speech.

In Great Britain, for example, a Racial Relations Act was adopted in 1965 to outlaw racist defamation. But throughout its existence, the Act has largely been used to persecute activists of color, trade unionists, and anti-nuclear protesters, while the racists — often white members of Parliament — have gone unpunished.

Similarly, under a speech code in effect at the University of Michigan for 18 months, white students in 20 cases charged black students with offensive speech. One of the cases resulted in the punishment of a black student for using the term “white trash” in conversation with a white student. The code was struck down as unconstitutional in 1989, and to date, the ACLU has brought successful legal challenges against speech codes at the Universities of Connecticut, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

These examples demonstrate that speech codes don’t serve the interests of persecuted groups. The First Amendment does. As one African American educator observed: “I have always felt like a minority person that we have to protect the rights of all because if we infringe on the rights of any persons, we’ll be next.”

Q: But don’t speech codes send a strong message to campus bigots, telling them their views are unacceptable?

A: Bigoted speech is symptomatic of a huge problem in our country; it is not the problem itself. Everybody, when they come to college, brings with them the values, biases, and assumptions they learned while growing up in society, so it’s unrealistic to think that punishing speech is going to rid campuses of the attitudes that gave rise to the speech in the first place. Banning bigoted speech won’t end bigotry, even if it might chill some of the crudest expressions. The mindset that produced the speech lives on and may even reassert itself in more virulent forms.

Speech codes, by simply deterring students from saying out loud what they will continue to think in private, merely drive biases underground where they can’t be addressed. In 1990, when Brown University expelled a student for shouting racist epithets one night on the campus, the institution accomplished nothing in the way of exposing the bankruptcy of racist ideas.

As a former Dean at the University of Illinois, I was often amazed at the number of people who disagreed with the ACLU’s position on Hate Speech.

Their remedy in dealing with so-called Hate Speech was to advocate some form of punishment for the offender–firing a non-tenured instructor, expelling a student, censoring a tenured professor or administrator.

The only thing missing, I used to think, were the dunking stools once used in Salem, Mass, or the public humiliation of the pillory and stocks on the university quadrangle.

In any case, literature and other forms of creative endeavor should never be restricted by those who believe THEY are the final arbiters of what can and cannot be said, written, or shown.

If that ever happens, then our Constitution will begin with the 2d Amendment–because the First Amendment will be but a distant memory.

[If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign-up for notifications box at https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent. You can also find my commentaries on the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us. And please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!]

In , Evelyn Beatrice Hall (under the pseudonym S. E. Tallentyre) illustrated Voltaire’s philosophy of free speech with the phrase: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The “progressives” have demonstrated there is nobody as intolerant as a tolerant authoritarian.

Thanks for the comment. Hall and Voltaire are right!