Now that the election is over (at least I hope so) I thought it might be a good idea to post something that, as they used to say on the old Monte Python TV show, is “completely different.” If nothing else it will take your mind off of the election–especially if you are on the losing side.

I posted the following piece a few days after the death of Muhammad Ali on June 3, 2016. When I was teaching journalism at the University of Illinois, I used to tell the story of how I went jogging with Ali on Chicago’s South Side in 1974. My students always got a kick out of it. I ran across the post while surfing my blog the other day and decided to share the story again with those who may not have seen it back in 2016. I hope you enjoy it.

Jogging With the Greatest

When I heard the news of Muhammad Ali’s death, I was reminded of my two encounters with the boxing legend while I was a reporter for the Chicago Tribune.

My first encounter was the result of one of those spur-of-the-moment assignments from the Tribune’s city editor.

“Yates,” he shouted at me. “Check this out. We have word that Muhammad Ali is down in Hyde Park somewhere. See if you can get an interview.”

It was the spring of 1974, and it was just a few months after Ali’s unanimous decision over Joe Frazier in New York. Ali was 44-2, having suffered a unanimous decision loss to Joe Frazier in 1971 and another upset split decision loss to Ken Norton in 1973.

But I wasn’t to interview Ali about boxing. I was to talk to him about his affiliation with the Nation of Islam and its fiery leader, Elijah Muhammad.

I made several phone calls and found that Ali was staying in a Hyde Park brownstone walkup owned by the Nation of Islam. I called the number for the brownstone and got somebody on the phone who identified himself as an assistant to the champ.

He clamped his hand over the phone’s mouthpiece, and I heard him mumble something about a Chicago Tribune reporter.

Then, I heard the unmistakable voice of Ali. “Tell him to come on down, but get here quick because we gotta get over to….”

Ali’s voice trailed off. I ran out of Tribune tower, hailed a cab, and headed to the Kenwood Park area of Hyde Park.

It took me about 20 minutes and when I arrived and rang the bell of the flat where Ali was staying. There was no answer.

“Damn,” I thought. “I missed him.”

Just then, I heard the sound of several footsteps bounding down the stairs from the third floor. It was Ali and three men, two of whom were Nation of Islam bodyguards.

“You that Tribune reporter?” Ali asked.

I nodded.

“Where’s Condon?” Ali asked, referring to Dave Condon, the Tribune’s legendary sports columnist who had interviewed Ali several times.”

“He doesn’t work Saturdays,” I said.

Then, looking me up and down, Ali said. “Think you can keep up?”

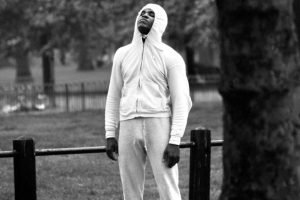

I was wearing a blue blazer and gray pants with a red and blue tie. On my feet were a pair of loafers. Ali was wearing a jogging suit and running shoes.

I must have looked puzzled because Ali laughed and said: “We’re joggin’ over to the Nation of Islam.”

And that was that. Ali took off, followed by his bodyguards and me bringing up the rear. I considered myself to be in reasonable shape—though nothing like Ali’s condition.

As we ran, I occasionally caught up to Ali and shouted a question at him, huffing and puffing between sentences.

Ali’s answers were always terse. “Yep, nope, maybe, who knows?”

“Good grief,” I thought to myself. “This is going to be a worthless interview.”

When we finally arrived at the building a mile or so later where Elijah Muhammad was about to speak to a large crowd of followers, I stopped outside.

“Come on in,” Ali said, waving at me. “Ain’t nobody gonna kill ya when you’re with me.” Then he laughed.

I followed him into the building. Then I saw a pay phone on the wall.

“I have to call my office,” I said.

“Go ahead,” he said. “Then you come on down to the front.”

I nodded. I told the office where I was and what I was doing. The person on the desk wished me luck. Then I walked down to the front of the building and stopped just in front of the stage where Ali was talking to Elijah Muhammad. Ali pointed to an empty chair in the front row and yelled, “Sit there!”

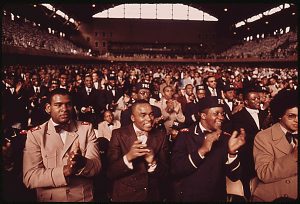

So I did. I looked around the large auditorium. As far as I could tell, I was the only white face in the building.

Ali took a seat on the stage. Moments later, Elijah Muhammad began talking. He spent some time talking about how the Nation of Islam is misrepresented in the media.

“We are not separatists, nor are we violent. We welcome our white brothers and sisters.” Then, looking directly at me, he added, “like this white brother right down there.”

I could feel every eye in the building trained on me. I looked up at the stage at Ali. He had an impish smile on his face. He was obviously enjoying himself, wondering how I might react.

So I did what all reporters do when they aren’t sure what to do. I began writing in my reporter’s notebook.

About 45 minutes later, Ali, his contingent, and I were outside the hall, getting ready to jog back to the brownstone.

“Well, one thing’s for sure,” Ali said. “Old Condon could never have kept up with me.” He was no doubt right. Dave Condon was 50 years old and probably weighed about 250 pounds.

Twenty minutes later, we were back at the Brownstone, and I had a 15-minute conversation with Ali before he excused himself to get ready for dinner.

We shook hands, and that was that.

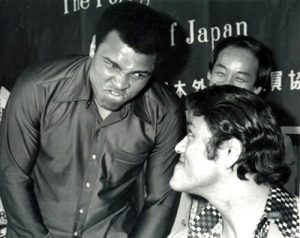

The next time I saw Ali was in June 1976 at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan in Tokyo. Ali was in town to do battle with a hulking Japanese wrestler named Antonio Inoki. Ali was coming off a knockout victory over Richard Dunn barely a month before and was the reigning WBC/WBA Heavyweight Champion.

Inoki was a karate expert and wrestler, and the object of the bout was to see who would win a match between a karate professional and a professional boxer.

The fight, held at Tokyo’s Nippon Budokan arena in front of 33,000 fans as well as an estimated 1.4 billion fans in 34 countries who watched on closed-circuit television, did not live up to the hype.

The rules for the fight said that Ali was not allowed to use any jabs—his most lethal weapon. Inoki could not grapple, throw or tackle Ali and could not land any kicks unless he had one knee on the mat.

The result was a strange spectacle in which Inoki lay on his back kicking at Ali’s legs while Ali danced around the 18-foot ring, trying to avoid the kicks. Ali didn’t throw a punch until the seventh round. In all, Ali threw just six punches during the 12-round fight.

From ringside, where I was covering the contest, I could hear Ali taunting Inoki, trying to get him to stand up and fight.

“He won’t rassle. He fights like a sissy. He’s a coward,” Ali yelled as he danced and shuffled around the ring.

I recall thinking that the whole thing reminded me of a crab battling a rooster.

The fight, which ended after the 12th round, was declared a “draw.” That didn’t sit well with the crowd in the Budokan, and they pelted the ring with bottles, cans, and other trash and yelled “money back, money back” in Japanese.

It was not Ali’s finest hour. Nor did he leave Tokyo unscathed. We later learned that Ali had suffered severe injuries to his legs as a result of Inoki’s kicks. His left leg was badly swollen and bleeding, and eventually became infected. There were also two blood clots in his legs that limited his mobility for the rest of his boxing career.

A day or so before the fight, Ali and Inoki had come to the Foreign Correspondent’s Club, where they met and mugged for the cameras.

I recall greeting Ali in the press club library along with several other correspondents.

To my great surprise and delight, Ali did a double take when he saw me.

“I know you,” he said. “You’re that joggin’ Tribune reporter.”

Ali then spent the next hour answering questions from reporters. As I reported at the time:

Ali’s green silk shirt was soaked with perspiration from the bright lights. Ali said after the Inoki contest, he would beat Ken Norton (he did), and then three months later, “I’ll take on George Foreman (he didn’t). Then I’m going to exchange my boxing gloves for a briefcase and sell trucks to the Arabs.”

With his talent for repartee, Ali could probably sell them sand.

Ali would go on to have seven more fights before he retired at 39 in 1981. He would win four and lose three of them, including the last two of his career—to Larry Holmes by TKO in 1980 and Trevor Berbick by unanimous decision in 1981. His final record in 61 professional bouts was 56-5. The Inoki battle was an exhibition and not included in his record.

Years later, as a Professor of Journalism at the University of Illinois, I used the jogging with Ali story to demonstrate how reporters sometimes need to be adaptable if they want an interview.

Of all the “war” stories I told in my classes, that one was always the favorite of my students.

It’s one of mine too.

–30–

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign-up in the notifications box at:

https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent.

You can also find my commentaries on Substack at https://ronyates.substack.com/ and the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us.

Please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!