The other day a front-page story in the New York Times grabbed my attention like few others.

The headline read: “At N.Y.U., Students Were Failing Organic Chemistry. Who Was to Blame?.”

The answer, readers learned, was not the students but the award-winning professor who taught the class.

To quote the story: “In the field of organic chemistry, Maitland Jones Jr. has a storied reputation. He taught the subject for decades, first at Princeton and then at New York University, and wrote an influential textbook. He received awards for his teaching, as well as recognition as one of N.Y.U.’s coolest professors.

“But last spring, as the campus emerged from pandemic restrictions, 82 of his 350 students signed a petition against him. Those protesting students claimed Dr. Jones’s class was just too hard and blamed him for their poor test results.

“Shortly before the beginning of the fall semester, the university terminated Dr. Jones’s contract. About 20 of Dr. Jones’s chemistry colleagues signed a letter, stating, among other things, that the university’s actions could “deter rigorous instruction” and “enfeeble proven pedagogic practices.

“The entire controversy seems to illustrate a sea change in teaching, from an era when professors set the bar and expected the class to meet it, to the current more supportive, student-centered approach.”

And there you have the state of higher education in America today.

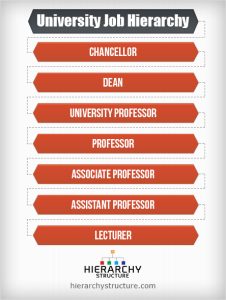

I speak of it from experience—not as a student but as a professor and dean for 13 years at the University of Illinois.

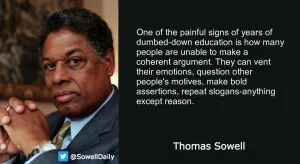

Don’t get me wrong. I am not singling out the University of Illinois, but during my time there as a tenured full professor and college dean I witnessed what can only be called the “dumbing down” of instruction and rigor as the university, like countless others, moved to so-called “student-centered” learning.

What exactly is “student-centered” learning?

It’s a combination of things, such as requiring professors to be “evaluated” by their students. That in itself is not such a bad thing. But the entire evaluation process has been corrupted by professors who feel they must “inflate” the grades of their students in order to receive a favorable evaluation.

That means that a student who maybe 40 years ago would have earned a “C” on a paper today will get a “B” or even an “A.”

The shift from teacher-centered learning to student-centered learning has been underway for decades as K-12 schools and universities embraced so-called “progressive education.”

In a student-centered environment, what matters is that the student feels good, not that the student is learning and succeeding. The teacher is a friend, not an authority figure. Subject matter is dictated by the student, not the teacher, and certainly not what society has always deemed important.

Here we see how toxic social-emotional learning supersedes reading, writing, and math instruction and how good grades cease to be an indicator of mastery but are given out like candy to prop up bruised egos.

To be fair, not all students like this new laissez-faire educational environment. Many of my students actually wrote in my evaluations that they appreciated how demanding and challenging my class was.

“Professor Yates’s class was rigorous but fair…and I learned a lot,” one student wrote.

As a teacher, I couldn’t have asked for a better evaluation. That student, by the way, earned a “B” in my class. I awarded “A’s” only when a student’s work was indisputably exceptional.

My philosophy in teaching journalism was to replicate as much as possible the tough and demanding environment students would encounter in a professional newsroom—without the yelling and blaspheming, I encountered when I began my career as a reporter with the Chicago Tribune.

Journalism is a highly competitive profession that requires practitioners to cultivate thick skins to survive and thrive. The coddling of battered egos is rarely found in newsrooms—or in most other professional environments.

Woke professors do their students no favors by indulging them. I am sure that is exactly how Professor Jones felt when he taught organic chemistry at NYU. Grade inflation and the lowering of standards mean graduates who are unprepared for the rigors of the real world.

Professor Jones saw that when he wrote in his defense: “In the last two years, [test scores] fell off a cliff. We now see single-digit scores and even zeros. After several years of Covid learning loss, the students not only didn’t study, they didn’t seem to know how to study.”

So here we are in this student-centered environment.

Blame the professor, not the student.

Fire the professor, but don’t flunk the student.

We are living in a dangerous dumbed-down nation where rigor is rejected in almost every key sector that once demanded it: education, the military, law enforcement, medicine, the law, business, and even the realm of politics, where trustworthy leadership has been supplanted by partisan dogma.

It is a nation in which everybody wins a trophy, nobody must accept responsibility, and achievement via merit is disparaged.

The result is an America that appears prepared to accept mediocrity rather than demanding excellence for the first time in its history.

If you don’t believe that, just look at the occupant of the White House!

[If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign up for notifications box on the right side of this post or at: https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent You can also find my commentaries on the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us. And please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!]

Over 50 years ago I graduated from Northern Arizona University with a degree in Forest Land Management. The curriculum was definitely a challenge. We literally had to master forest management but also watershed management, range management and recreation management. We had to write an interdisciplinary management plan for real ranches for the ranch owners as part of the program.

The dean did not allow any of us the have a “minor”. His position was that if “you have enough time to get a minor in anything you were not serious enough about forestry”. Same went for any varsity sport – but we did have some pretty bloody intramural football games with the fraternities. As a side note: we had one smoke jumper who routinely laid waste to varsity starting linemen!

The option if you thought the courses were too hard was simple – change your major. Engineering was considered a much easier curriculum.

Now the School has l”behavioral psychologists” as professors and I doubt any graduate understands what makes a tree grow, how to manage water retention through forest practices and the integration of range management.

I think you can see the results of what you are talking about here in California with our constant and ubiquitous forest fires. When President Trump criticized California’s poor forest management, Newsome and the Dems attacked him for refusing to place the blame on, you guessed it, climate change.