(Today I am pleased to re-run a story that recently appeared in the Asia Times about my former Chicago Tribune colleague Don Kirk. In the piece, Don talks about the changes he has witnessed during 50 years of covering a tumultuous, changing Asia. Don was one of the most persistent, aggressive, and prolific reporters ever to cover Asia. We worked together for a short while when I was named the Tribune’s Tokyo bureau chief, and Don was headed for a journalism fellowship back in the U.S. Not long after that Don left the Tribune, but we bumped into one another often over the years when we were covering the same stories. Few American journalists have ever covered Asia as long and comprehensively as Don Kirk. My thanks to the Asia Times. Read on!)

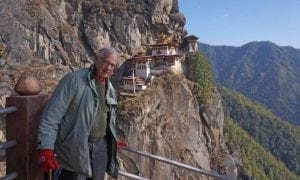

Tables were thumped, bottles were emptied and off-key songs resounded in Seoul’s La Cantina – the oldest Italian restaurant in South Korea – on a recent Saturday evening as foreign correspondents gathered to celebrate the 80th birthday of one of their number: Don Kirk, an American journalist who has been reporting on Asia since 1965.

Since that year, the still-working old Asia hand has built up a formidable clipping file of stories covering everything from Vietnam’s Tet offensive to Korea’s “Economic Miracle,” while also finding time to pen a shelfful of books and amass families on three continents.

Living dangerously

The New Jersey native was first bitten by the journalistic bug as a student, doing summer reporting for his local paper The Plain Field New Jersey Courier News. “I was covering the board of education, the town council, the police and rewriting a lot of press releases from churches and the Lions’ Club,” he said. “I really wanted that job: It paid US$55 per week, and looking at inflation now, it was not that terrible!”

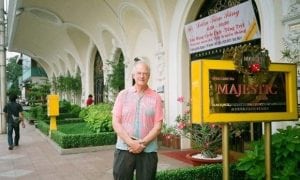

More distant horizons soon beckoned. Kirk first traveled to Asia in 1962 when, as a Fulbright Scholar, he flew to New Delhi to undertake a project on the Indian media. After an interregnum in New York and Chicago, in 1965, he paid his own way to Hong Kong, where he found work a sub-editor of the South China Morning Post, before decamping to Vietnam in the early days of the US troop build-up for a story on black GIs.

Then it was Indonesia, where an abortive coup took place. For the chaotic island nation, this would be “The Year of Living Dangerously.”

“I was stringing for a bunch of papers including the New York Times, the Washington Star and the Daily Telegraph, traveling around Indonesia,” he recalled. “About 300,000 people were killed in that bloodbath.” Despite the scale of the carnage, he was not unduly traumatized, courtesy of prior experience in inner cities in the US. “I had previously covered stories in Chicago, and New York so had covered the run of fire, police, and scandal.”

His most vivid memory was the sacking of the Chinese Embassy. “I covered the riot and the sacking of the Chinese embassy and remember this Chinese diplomat screaming in the face of the foreign minister,” Kirk said, reflecting on reporters’ luck: “I remember the NBC correspondent left the day before and missed that story!”

But there was more pressing business for US reporters in Southeast Asia that year: America was shifting from military advice to kinetic engagement in South Vietnam. Kirk returned to the country with Businessweek, “for a story on the economy and all the great things the Americans were doing there, the prospects for US investment – but really, I was interested in covering the war.”

The draw of war

With America’s eyes increasingly focusing on Vietnam, Kirk relocated to Saigon. The press corps there would expand across the greatest playground for war correspondents in modern history.

“We were a disputatious group, some good people, some not so good people – I won’t say who fell into which category!” Once accredited and armed with a Military Assistance Command Vietnam press pass, reporters had the run of the war. “You had incredible freedom; you could jump onto a helicopter and go just about anywhere free of charge,” he said. “You could go on patrol, you could go on and off bases and into officers clubs, just by showing your press card. You don’t have that freedom now, partly as a reaction against Vietnam.”

A firewall rose between field reporters and bureau journalists. “There were some guys who were gusty and covered a whole lot of stuff out of town, and some who stayed in wire service bureaus and did not get out but were quite well known. Some freelancers wrote brilliant stuff.”

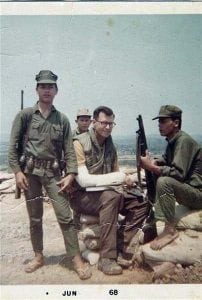

Kirk was in the midst of some of the heaviest fighting as the communist Tet Offensive was unleashed in 1968. “I was in Danang when word came that they’d hit the embassy and other things, and I saw a lot of fighting,” he said. “I simply asked the troops what the hell was going on – you could do that in those days! You developed a kind of refined sense of where was secure and where was not.”

He was on hand when the most famous “quote” of the Vietnam War surfaced.

A press briefing was held in a town from which enemy forces had been driven, but with massive collateral damage. Kirk takes up the story. “They gave us a great briefing and this officer was flipping charts, and Peter Arnett piped up, ‘So, you had to destroy this town in order to save it?’ and the major kind of said, ‘You could say that.’ I did not include the quote in my story as the major had not said it, and my editor got back to me and asked, ‘Why did you not include this?’ So Peter Arnett had made his own quote, and that became the watchword of the anti-war movement.”

Still, Kirk got “the best quote of my career” in a similar situation. In another devastated village, he interviewed a civil affairs major who had called in air strikes. “He said, ‘First I annihilate them; then I rehabilitate them!’” Kirk said. “The Pentagon went nuts and came up with all kinds of denials. I suspect that major did not make lieutenant colonel!”

His most dangerous moment gave him an appreciation for the battering the enemy endured. “There was a ceasefire, and I went up a road north of Saigon where the North Vietnamese Army was. They had a big banner, so I went up with my driver and was talking to the NVA when this plane started circling and dropping bombs. We started running back down the road, and you could hear the goddam bombs coming down, and we just fell into the ditch beside the road, we ran through the smoke and then [the pilot] began firing at the NVA with the miniguns in his plane. We got back to where the [South Vietnamese] were. We did not ask why this happened – we were so goddamned relieved we had survived, we just did not give a shit.”

And between interviews, assignments, and operations, there was the extraordinary social whirl of Saigon. “You got caught up in life in Saigon, which had good restaurants and bars and some of the most delectable bar girls,” he recalled, trying, but failing, to suppress a grin. “It was said that the girls got their basic training from the French and went to grad school with the Americans!”

Tragedies and turmoil

As his byline became known, Kirk spread his wings across the region. “I first came to Korea in 1972 to cover the North and South Red Cross talks, and they were talking family meetings, trade, commerce, getting together, cultural contacts, all that,” he said. “In fact, all they are talking about today – the one difference is they were not talking denuclearization.”

Meanwhile, the US had lost faith in its Vietnam mission. Collapsing morale on the home front was reflected among troops. “I got a sense, interviewing GIs, of their sense of loss,” he said. “They went there to fight a war, and at a certain point, it became clear that we were not fighting to win.” The Americans went home, and in 1975, Kirk was appalled by the falls of Phnom Penh and Saigon. “I thought it was very sad, very tragic; I could not believe that we had basically run out on them,” he said. “People think how terrible we were to the Vietnamese, but two million came to the US.”

Along with communist victories in Southeast Asia, there was turmoil elsewhere in Asia. In 1980, Kirk covered a watershed event in Korea: The uprising in the city of Gwangju, protesting the creeping coup launched by General and subsequently president Chun Do-hwan. “Was it an uprising? A revolt? Were they rebels?” he mused. “They were going around in trucks and waving rifles and shouting slogans, and you could not believe that Chun would let them take over the city.”

Some 200 people were killed as the army retook Gwangju, an event that ignited a simmering fury in Korea that lasts to this day, with many convinced that Washington aided and abetted the generals. “It was an ugly incident and raised questions about what kind of government we were supporting,” Kirk said.

He was also in the Philippines for the “people power” revolution that toppled Ferdinand Marcos. “I had interviewed Marcos a couple of times, and when he was overthrown, you could sneak into Malacanang Palace,” he said. “I went in, and there was still food on the table, plates of uneaten food – they had left in a hurry.”

Back in Korea, he covered protests against an authoritarian government that raged around Seoul before the 1988 Olympics. “I visited the campus of Korea University and saw these hundreds of Molotov cocktails piled up outside the Student Union building,” Kirk said. “The police did not want to invade the campus; they did not want that kind of ugly stuff going up before the 1988 Olympics.”

He missed the massive protests of 1987, in which Korea transitioned to full democracy: “It was just one of those stories,” he said – but he would recall the 1980s protests in 2016 when millions again hit Seoul’s streets to boot out the now-jailed President Park Geun-Hye.

Asia rising

Despite war and turmoil, by the 1980s, Asia’s manufacturers were fighting to the forefront of the global economy, forcing ex-war reporters and political news junkies to transition. “There was this new emphasis on economic reporting,” he noted. “You did not have all this Dow Jones or Reuters Financial or Bloomberg at all, but now economic reporting dominates the press corps, and I got into it myself by interviewing business people, analysts, and specialists.”

Researching a book on Hyundai, Kirk encountered both the opacity and the charisma of Korea’s first-generation conglomerate chairmen. “I had interviews with the top people including [Hyundai founder] Chung Ju-Yung – even in those days it was hard to get an interview – and they were not very revealing, all they wanted to do was talk up Hyundai,” Kirk said.

“Chung knew how to speak in generalities and not reveal much. He was a man of many faces: He could speak soberly, or could put down a person in a very shocking way, or could be genial singing in a karaoke.”

The business of reporting was climbing the technological ladder. “Don’s first posting was in Indonesia where he was the young cub in the group and used to get the taxi out to the airport,” recalled an ex-colleague. “Don was always very good at getting his stories out first.”

Kirk himself revealed the secret. “I sent stuff by cable, and it was going out so slowly, so I struck up a relationship with the cable guy and gave him tea and $20, and I got my copy out faster!” he recalled. In Vietnam, reports went by telex – “I got pretty good at doing telex by myself,” Kirk said – but now the internet has equalized filing speeds for everyone, reducing what used to be cut-throat filing competition.

Looking back, looking forward

Kirk today cuts an avuncular figure among Seoul’s foreign correspondents, most of whom are half his age. He announces himself at the Foreign Press Center with this daily greeting – “What’s the news?” and is noted for an eccentric habit. Whenever free snacks are available, he appears, and the pockets of his sports jackets are customarily filled with loose nuts and cookie crumbs.

By Kirk’s own account, his frugality dates back to Vietnam: “I did not tend to buy drinks for the bar girls, so they used to say, ‘Ah, you cheap Charlie – you number 10!” he admitted.

He was not always so affable, though. “He got banned from a news agency office as he would go in there and look at their stories,” recalled a former colleague. “But reporters in those days were not people with masters’ degrees in international economics, they were a rough and ready crowd, and Don would prod away at his colleagues to make sure he did not miss anything. He burned some sources – people would regret telling him things.”

He retains a reporters’ healthy disrespect for authorities – even the most dictatorial kind. During a 2005 trip to Pyongyang, this writer was summoned to speak to a perplexed North Korean official, who was perusing a list containing visiting reporters’ personal information. I was asked whether I had heard of the university Kirk had attended; the officials had, apparently, never heard of it. On the list, Kirk had reported his alma mater as “The School of Hard Knocks.”

With his gravelly mien, loud voice and habit of barging in, Kirk may be unsuited for an editorial desk or teaching position. Still a field man, he files for outlets ranging from CBS Radio to The Daily Beast and Forbes. “Sometimes when you go somewhere you see or don’t see things by happenstance, but even if you miss them, you still have interesting conversations and experiences – unlike being a professor of journalism,” he said. “I have never, by the way, been a professor of journalism – thought I had taught a few lectures here and there.”

Why, at this late stage, is he still freelancing? “Why not? I am still sort of excited by the story, frankly,” he said. “And I say, ‘I have no job from which to retire. Therefore, I cannot retire, so I keep working!’”

Familial expenses may be one reason. A lothario in years past, Kirk has survived American and Japanese wives and a Philippine relationship; he is now wedded to a Korean. One son has graduated from Cambridge; another is a US Marine.

He has no regrets. “They say the luckiest man in the world has a Japanese wife, a French girlfriend, a Chinese cook and an American car, and I have had them all – though never at the same time.” He adds, after a second, “But now it is no longer an American car!”

Looking forward, he is wary of Beijing. “China is taking the South China Sea, challenging Japan and holds great influence on the Korean peninsula,” he said. “I don’t think China will democratize … [Chinese president] Xi Jinping may go down in history as one of the great leaders, or a terrible dictator.”

He sees Asia’s two giants on a collision path. “China is a lot stronger than India,” he said. “India is getting stronger, but I don’t see India as having the discipline or strength to stand up to China – but India has some good friends, including America.”

In the Trumpian era, Kirk hopes the US will remain engaged. “I felt like we were a severe disappointment to the Vietnamese, we let them down, and now we have a real obligation to the Korean people,” he said.

Although the bulk of his output now comes from Korea, his reportorial heart lies in Vietnam. “The story of my life was Vietnam,” he said. “It was ‘the best of times, the worst of times’ – which is a terrible cliché, but a pretty good line!”

Despite the millions of words he has filed, and all he has witnessed over half a century in Asia, Kirk makes no great claim to wisdom. “People say, ‘We should do this or do that,’ but at the age of 80, I still don’t know,” he said. “I am just a reporter.”