(Because this is “Banned Books Week,” I thought I might re-post a commentary I did a while back about how many American schools have decided to ban Harper Lee’s prize-winning book, “To Kill a Mockingbird.” It is not only a wrong-headed policy; it is a dangerous act of censorship that is all too common in today’s schools. Please read on).

I first read To Kill a Mockingbird when I was in high school. It was a time when our nation was in the midst of a heated struggle for civil rights.

There were marches, sit-ins, and violent confrontations with police in Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.

Many people were injured, and some were even murdered.

For a kid growing up in Kansas, it all seemed so remote, so isolated from the reality with which I was familiar.

But the story that the late Harper Lee told in her brilliant 1960 Pulitzer Prize-winning book helped me see things that were not evident in my rural Kansas background.

To Kill a Mockingbird left a profound impression on me and the lessons I learned from reading it helped define the way I have lived my life.

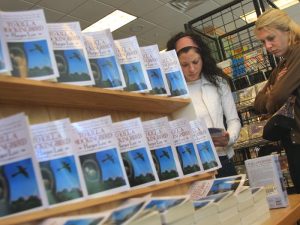

So, when I learned that To Kill a Mockingbird has been banned in many American schools, I was shocked and saddened.

If there is ONE book American children should read, it is THAT book.

Instead, many American schools have embraced Marxist-inspired Critical Race Theory, which posits that “race is a social construct” and that racism is “systemic.” CRT reformulates the old Marxist dialectic of oppressor and oppressed, replacing the class categories of bourgeoisie and proletariat with white and minority identity categories.

Most alarmingly, it tells children that their skin color is what defines them—not the content of their character, as Martin Luther King once said. CRT says if a child is white, that child is an inherent “oppressor.” Children of color, meanwhile, are the “oppressed.”

I won’t continue with a dismantling of the racist and divisive dogma of Critical Race Theory or the equally fallacious 1619 Project, which argues America was founded not to free itself from domination by the British Empire but to perpetuate and protect the institution of slavery. I have often posted about those two Marxist-inspired and preposterous theories, and you can find those posts elsewhere on my blog.

Instead, I prefer to reexamine the positive messages about race, civility, and tolerance that I found in To Kill a Mockingbird.

If you haven’t read the book or have forgotten the story, here is a brief refresher.

The book, written just as the Civil Rights Movement was getting underway in the United States in the early sixties, tells the story of incidents in Maycomb, Alabama, in the 1930s. The narrator is Scout Finch, a six-year-old girl whose father, Atticus, is a prominent lawyer in the town.

Atticus agrees to defend Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman, which makes the Finch family social pariahs. The book follows Scout for three years as she and her brother, Jem, learn to navigate the racism in their community.

One of the most powerful moments occurs when Atticus Finch gives his young daughter Scout the following advice:

“If you can learn a simple trick, Scout, you’ll get along a lot better with all kinds of folks. You never really understand a person until you consider things from their point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

I never forgot that advice about the importance of developing a sense of empathy

Another moment explains the title of the book. After giving Scout and Jem air rifles, Atticus tells them:

“I’d rather you shot at tin cans in the backyard, but I know you’ll go after birds. Shoot all the blue jays you want, if you can hit ’em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.

“That was the only time I ever heard Atticus say it was a sin to do something, and I asked Miss Maudie about it.

“Your father’s right,” she said. “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

It may not seem that these passages have much to do with the racism and intolerance the book reveals and illustrates, but they do.

On the one hand, these lines show that Scout is learning that the community she lives in shares a set of values. Atticus isn’t the only person who thinks it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird; Miss Maudie, the neighbor across the street, does, too. Ultimately, the mockingbird symbolizes goodness and hope, so this passage teaches readers about the difference between good and evil. The mockingbird represents “good,” and killing it—or, rather, destroying innocence—is evil.

Here’s Atticus discussing conscience:

“Well, most folks seem to think they’re right and you’re wrong …”

“They’re certainly entitled to think that, and they’re entitled to full respect for their opinions,” said Atticus, “but before I can live with other folks, I’ve got to live with myself. The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule is a person’s conscience.”

And here’s Atticus giving his views on racism, ca. 1930 in Alabama:

“The older you grow, the more of it you’ll see. The one place where a man ought to get a square deal is in a courtroom, be he any color of the rainbow, but people have a way of carrying their resentments right into a jury box. As you grow older, you’ll see white men cheat black men every day of your life, but let me tell you something, and don’t you forget it—whenever a white man does that to a black man, no matter who he is, how rich he is, or how fine a family he comes from, that white man is trash.”

At one point, in court, Atticus gives us his views on equality:

“But there is one way in this country in which all men are created equal—there is one human institution that makes a pauper the equal of a Rockefeller, the stupid man the equal of an Einstein, and the ignorant man the equal of any college president. That institution, gentlemen, is a court. It can be the Supreme Court of the United States or the humblest J.P. court in the land, or this honorable court you serve. Our courts have their faults, as does any human institution, but in this country, our courts are the great levelers, and in our courts, all men are created equal.”

Toward the end of the book, Jem and Scout are discussing the idea of family with their Aunt Alexandra.

“What if he was kin to us, Aunty?”

“The fact is that he is not kin to us, but if he were, my answer would be the same.”

“Aunty,” Jem spoke up, “Atticus says you can choose your friends, but you sho’ can’t choose your family, and they’re still kin to you no matter whether you acknowledge ’em or not, and it makes you look right silly when you don’t.”

To Kill a Mockingbird contains many immutable truths such as these.

To the school boards who feel the need to ban this excellent book with a multitude of valuable life lessons, I would say this:

I have read this book a few times, and I could find no life lessons that are iniquitous or unsuitable for children to learn, nor have I found any that should be banned from schools. The handful of life lessons I have shared here should be taught to all school children. And it wouldn’t hurt for some adults to learn them also.

So why is it being banned in our nation’s schools?

The most common complaint about challenging the book and removing it from school libraries has traditionally been its use of the “N” word. There is also some violent content, a discussion of rape, and references to child abuse—both physical and sexual.

Others complain that the book’s messages about race are outdated and harmful today. Some see Atticus Finch as a “white savior” figure, and others believe the book’s depiction of racism is flawed because it comes from a white point of view. Others view the book’s portrayal of racism as potentially upsetting to young Black readers.

Okay. I get it. But the book is historical fiction and accurately portrays racism in 1930s Alabama. Those who write historical fiction, as I do, strive for historical accuracy when constructing stories set in the past.

In my books, I have characters in the 19th century using pejorative terms for Mexicans, blacks, and Native Americans. Why? Because that was the way, some white Americans referred to minorities in that era. At the same time, those minorities use pejorative words to describe whites.

That’s the way it was in the past. There was a coarseness to life and a lack of sensitivity to others. If you write accurate historical fiction, you cannot hide warts and blemishes of the past with a patina of literary powder and paint.

The racist vernacular aside, To Kill a Mockingbird contains a surfeit of universal truths that those who read it will learn: how to understand those different from ourselves; recognizing that others possess emotions, senses, and feelings just as we do; and that to see another individual’s humanity we must learn to accept and try to understand his or her perspective.

But in today’s divided and polarized nation, we don’t seem to have the time to judge others fairly or respectfully. If you don’t follow the dogma of the PC and cancel culture mob, and if your perspective is at odds with theirs, then you run the risk of being banished and “canceled.”

For that very reason, the message in To Kill a Mockingbird is one to which every child and adult should be exposed—to see life from another’s point of view, to “climb in their skin and walk around.”

The surprise in Harper Lee’s book is who, in the end, winds up being the savior. It is not Atticus Finch. It is the reclusive Boo Radley, the shunned, disparaged, and dreaded introvert who Scout and Jem terrorized every summer.

Jem and Scout’s harassment of Boo Radley stemmed from the malicious gossip and insinuation about him in the town. In their eyes, Boo was some kind of monster who ate squirrels raw and who drooled most of the time. From what we learn about Boo, he may well be autistic—which is yet another form of prejudice the book draws attention to.

Ultimately, it is Boo Radley who saves Scout and Jem from being murdered by Bob Ewell, the story’s main antagonist. Ewell, an evil malcontent, serves as a symbol of both prejudice and racism in the book.

It is also Boo Radley who teaches Scout the crucial lesson about perception when, at the book’s end, she stands on his front porch looking at the town of Maycomb from Boo’s viewpoint.

So will someone please tell me why this book is banned in many American schools?

Rather than banning To Kill a Mockingbird, it should be required reading from middle school all the way through college. Its lessons are not only important in today’s divided America, they are indispensable and very much needed.

To ascribe 21st-century values and standards to a book set in the 1930s is to deny our history and the struggles Americans of all stripes underwent in coming to grips with racism as well as the societal changes that were beginning to emerge in the South.

To Kill a Mockingbird is not a book that schools and colleges should sweep under the rug of history. Some parts of the story may be uncomfortable, but if we are to understand the past and its inevitable connection to the present, we must not be afraid to face the truth of our history.

Honorable nations do not revise and sanitize their history. They learn from it. We should too.

[If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign up for notifications box on the right side of this post or at: https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent You can also find my commentaries on the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us. And please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!]

Thank you, Ron, for this wonderful article refreshing old memories and pointing out important life lessons I’d missed as a teen growing up in Alabama when TKAM hit the shelves. Talk about not seeing the forest for the trees. Your article opened my eyes to passages I’d skimmed through as a naive youth. A piece of trivia mentioned before, the Dill character in TKAM was based on the pre-school-age Truman Capote (before he changed his name), who was Lee’s BFF in Monroeville.

Hi, James. I always find something new and relevant in this book whenever I pick it up. Lot’s of truth in it that sadly is not being shared with kids because teachers have decided to embrace CRT.

Excellent redux. Great phrase: ” If you write accurate historical fiction, you cannot hide warts and blemishes of the past with a patina of literary powder and paint.” Thank you, again.

Thanks, J. C.