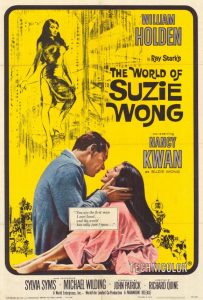

My introduction to Hong Kong was via the 1960 film The World of Suzy Wong, starring William Holden and Nancy Kwan.

The movie was based on the 1957 novel of the same name by British author Richard Mason. It is a classic East meets West story in which a British artist falls in love with his Chinese model, who also happens to be a prostitute.

From the moment I watched that movie, which was shot entirely in the old British Crown Colony, I knew I would visit Hong Kong someday.

I finally did that in 1974 when I was posted to Tokyo, Japan, as the Chicago Tribune’s Far Eastern Correspondent. On my way to Vietnam to cover the final throes of that war, I stopped over in Hong Kong for a couple of days.

I wasn’t disappointed.

Hong Kong in the 1970s still retained its old colonial flavor, and in 1974, it still had 23 years before the British would hand the place back to China. Hong Kong was an eclectic place bursting with all of the mysteries and inscrutability of the Orient that an impressionable and newly minted correspondent from Kansas could want.

For two days I did everything possible to absorb Hong Kong into every fiber of my being. I wandered the bustling streets of Kowloon; visited the venerable Peninsula Hotel and its storied lobby; rode the Star Ferry between Tsim Sha Tsui and Hong Kong Island’s Wanchai district (where the fictional Suzy Wong plied her trade); took the mile-long funicular “Peak Tram” up to Victoria Peak; and took the 40-minute taxi-ride to Stanley Market on the far south side of Hong Kong island.

But most of all, I just wandered the streets of Kowloon and Hong Kong Island taking in the eclectic and myriad scents of Hong Kong—the Cantonese, Hunan, and Szechuan food; the mysterious spices; the exotic fragrances.

Even though the Cross Harbor Tunnel under Victoria Harbor opened in 1972, as far as I was concerned the only way to travel between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon was on the Star Ferry. The 12 green and white ferries have been making the 8-minute trip between Tsim-Sha Tsui and Central Hong Kong Island since 1898, and the fare of HK $2.70 (about 34 U.S. cents) for the upper deck and HK $2.20 (about 28 cents) for the lower deck hasn’t changed in years.

During my almost two decades of working in Asia, I returned to Hong Kong many times. It was always one of my favorite destinations. So perhaps a little history lesson is in order for those of you unfamiliar with Hong Kong’s connection to Great Britain and how it was once separated politically, if not physically, from the Chinese mainland.

To understand that you need to go back to the so-called “Opium Wars” between Great Britain and China (1839–1860). After those bloody military and tense trade battles, China was forced to cede Hong Kong Island and a part of Kowloon to Great Britain in perpetuity.

In 1898, Britain negotiated a major land expansion of the Hong Kong colony and signed a 99-year lease with China. That lease ended in 1997, at which time Britain returned Hong Kong to China as a “Special Administrative Region” (SAR) called the “Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China” (HKSAR).

That’s where we stood until May 2020, when China reneged on the 1997 legal agreement assuring Hong Kong would maintain its democracy, capitalism, and autonomy under a “one country, two systems” framework.

In 1997, under the doctrine of “one country, two systems,” China allowed the former colony to continue to govern itself and maintain many independent systems for a period of 50 years. That doctrine was guaranteed by something called the “Basic Law,” which also established English as one of Hong Kong’s official languages.

Article 2, of the Basic Law, that both mainland China and Hong Kong agreed to, says: “The National People’s Congress authorizes the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region to exercise a high degree of autonomy and enjoy executive, legislative and independent judicial power, including that of final adjudication, in accordance with the provisions of this Law.”

Under that agreement, Hong Kong’s economy transitioned to a mainly service economy, with manufacturing shifting to the mainland. It also developed what is considered the freest economy in the world. With a GDP of $362.9 billion in 2018, it is currently the world’s 35th largest.

As of May 22, 2020, all that changed. China’s government announced that it would allow mainland state security agencies to operate officially in Hong Kong, effectively allowing Beijing to impose national security laws on Hong Kong. That means it will be able to repress and arrest political opponents at will under the same Communist Chinese mandate that exists on the mainland. To show it means business, pro-democracy protest leaders have been arrested—a move that has gone largely unreported.

In short, the world is watching the death of freedom in Hong Kong, and with it, the death of any semblance of opposition.

So far, most of the Western world has said nothing and done nothing, with the exception of President Trump. He has repeatedly and publicly condemned China’s seizure and obliteration of the 1997 agreement that guaranteed Hong Kong’s political freedoms as well as an economy characterized by low taxes, free trade, and minimal government interference.

Last week Trump declared that because of Beijing’s action, Hong Kong is no longer sufficiently autonomous from China and as a result, he revoked the former colony’s “special status.” That revocation means targeted sanctions, tariffs, and trade restrictions can be imposed which will radically alter the fate of a city that has served for decades as China’s economic gateway to the world.

When I consider what is about to happen to Hong Kong, I am glad I had the opportunity to spend time in the place during its prime when it was still a British Crown Colony.

The Hong Kong I once knew is fast disappearing and soon will be indistinguishable from the repressive nation ruled with an iron-hand by the Chinese Communist Party.

When that happens, one more bright light of freedom and liberty will be extinguished on our planet.

(Note: Please join ForeignCorrespondent this Thursday, June 4, for my retrospective on the Tiananmen Square massacre–a horrendous event that I covered on that date in 1989. It may give you a taste of what could happen to Hong Kong if its people refuse to buckle under to Beijing’s iron-fisted rule)