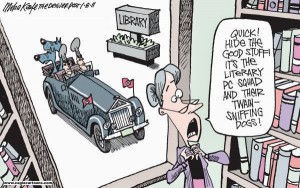

I posted this commentary a couple of years ago. Since then, nothing has changed. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie books are still banned in many schools today and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s name is still excised from the award once named in her honor. This is censorship in action. All authors should be appalled and the Association of Library Service to Children should be ashamed. To learn more about this literary suppression and bowdlerization, please read on.

In yet another example of twenty-first-century political correctness invading and perverting the past, the Association of Library Service to Children voted unanimously recently to remove Laura Ingalls Wilder’s name from the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award and instead call it the Children’s Literature Legacy Award.

Why, might you ask, would the ALSC, a division of the American Library Association do something like this to such a beloved author as Wilder? Because of her portrayal of minorities and Native Americans in her “Little House on the Prairie” novels, the ALSC says.

Nevermind that Wilder was the first to win the award in 1954 when she was in her late 80s and nearing the end of her life. Until her death in 1957 she was beloved for the semiautobiographical “Little House” children’s books, which are fictionalized versions of her family’s adventures traveling the western frontier in their covered wagon and its encounters with Native Americans.

“This decision was made in consideration of the fact that Wilder’s legacy, as represented by her body of work, includes expressions of stereotypical attitudes inconsistent with ALSC’s core values of inclusiveness, integrity, and respect, and responsiveness,” the Association for Library Service to Children said in a statement.

In its decision to remove Wilder’s name from the award, the library association cited “anti-Native and anti-Black sentiments in her work.”

What a bunch of hooey.

The reason is quite simply this: The ALSC has decided to apply 21st-century attitudes about race and minorities to literature that accurately portrays those attitudes as they existed in the 19th century.

Authors of historical fiction should be outraged by this kind of gratuitous censorship and suppression. I know I am.

While passages within Wilder’s work reflect many attitudes of the era, the section of literature most often cited in this debate is from the 1935 story “Going West,” about a pioneering family.

In the book, the character “Pa” explains that on the land his family is seeking, “there were no people. Only Indians lived there.”

In 1953, Wilder changed the passage to say, “there were no settlers there. Only Indians lived there.”

That change has not appeased the politically correct crowd, however. Never mind the fact that in her books Wilder correctly portrayed the pioneer environment in which she grew up. That apparently offends people who say she should have been “more inclusive” in her books and provided more examples of “diversity.”

Once again, what a bunch of hooey.

I belong to a lively Historical Novels online discussion group in which authors engage in discussions ranging from how one researches historical novels to selecting book titles. Most recently someone started a discussion about whether or not we authors should be politically correct when writing historical fiction. The result was a long thread of comments from authors of historical fiction.

Almost to a person, authors of historical novels say political correctness should NEVER influence how we write about the past. To do so is to be disingenuous to those who read our books.

Our job as authors of historical fiction is NOT to “clean up” or rewrite history, so the sins of the past are expunged from our consciousness. The fact is, overt racism, religious oppression, and other forms of discrimination have been part of life for several thousand years. They still are.

You can see how political correctness has distorted the literary landscape when writers of historical fiction attempt to cleanse offensive language in their books that once was used to describe certain races, classes, religions, and ethnic groups.

As one group member said: “Let’s not only get political correctness out of historical fiction, let’s get it out of society. If you wrote a Civil War story and had a character refer to a black person as an African-American, you ought to be horsewhipped.”

Let me say it forthrightly and plainly: political correctness has no place in historical fiction or, for that matter, in any other form of literature. If you are striving to create accurate characters and events in a novel about the past, you must create characters that think, speak, and act the way they did during the period in which the story is set. You cannot impose inclusiveness and diversity retroactively by substituting today’s anodyne language for the often provocative and offensive vernacular of the past.

To inflict today’s political correctness on literary art is to censor and suppress creativity. PC has already overrun and dampened free speech and innovative thought in our schools and on college campuses. God forbid that the thought police should be successful in invading the province of historical fiction too!

The PC thought police have been successful in getting American classics like Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain and Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe removed from some school libraries because of their use of language and racial characterizations prevalent in 19th Century America. They have even convinced a few publishers to issue “cleansed” versions of Mark Twain’s work with some passages and descriptions rewritten and some offensive words removed.

That is nothing more than the desecration of art. As writers of historical fiction, it is incumbent upon us to be truthful in our depictions of times past–ugly warts and all.

For the PC thought police, it is not only the politically incorrect word or name that is the problem. It’s a person’s attitude, an individual’s mindset, his or her ability to think freely and express himself or herself in a particular way that the PC bullies want to control. If an individual’s opinions do not conform to their Weltanschauung, then those views should not be expressed. This is intolerance in the extreme.

The underlying question is this: are we really ‘free’ in what we choose to write and say? Do we indeed still have ‘freedom of speech’ as guaranteed by the First Amendment, or do we now SELF-CENSOR because we are afraid of ‘the backlash’?

For those who write or who create other forms of art, these are critical questions that need to be considered. I for one will not be bullied by the PC thought police in my historical novels. I want my work to accurately reflect the time in which my novels are set.

Politically correct speech and its offshoots of intolerance, censorship, and social intimidation are the greatest dangers to free speech since the First Amendment was inserted into our Constitution in 1791. If the PC thought police manage to eviscerate that critical component of our Constitution, freedom of speech will cease to exist.

Laura Ingalls Wilder does not deserve this kind of bowdlerization and maleficent treatment by the Association for Library Service to Children and its parent, the American Library Association.

Authors of historical novels should be sickened and disgusted by this treatment of one of America’s most treasured authors.

In the meantime, the Children’s Literature Legacy Award will remain a fraud because by cleansing the muck and ignominy from our collective history we are being dishonest and insincere with the children we are charged with educating.