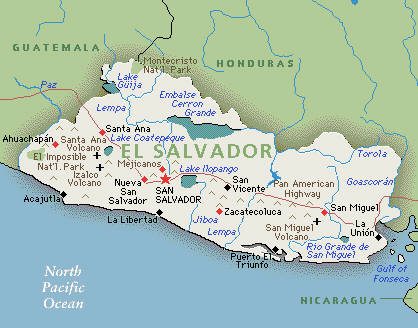

Between 1978 and 1982, I spent a lot of time as a Chicago Tribune foreign correspondent in Central American countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama, and Nicaragua — all of which were experiencing vicious uprisings and revolutions. From time to time, I post one of the stories I wrote from places I covered. The following story was written in 1982 in San Salvador, the nation’s capital.

El Salvador was a different country in 1982. Gangs, such as the infamous MS-13, had yet to emerge in a nation beset with one of the bloodiest uprisings in Central American history. Few El Salvadorans attempted the dangerous journey north through Mexico to cross into the United States, as thousands did during the Biden administration, when the US border was wide open.

In the 1980s, most Americans were largely ignorant of the war being waged in El Salvador, and those who were aware of it tended to ignore it. However, journalists who covered El Salvador discovered it was one of the most dangerous and violent places on earth. In fact, it is the only war I covered in which I carried a handgun. Journalists were fair game for the guerrillas, government forces, and the ubiquitous death squads that roamed the nation. I figured if I was going to be targeted by any of these groups, I would go down fighting. Fortunately, I never had to test that brash dollop of bravado. Please read on.

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador—In 1937, a year after Juan Chong arrived in San Salvador first via Canton and then Hong Kong and opened the Canton China Bar and Restaurant, an American journalist dropped in for a drink.

“I think he was from New York,” said Chong, shifting his 80-year-old frame in the old wicker chair behind the bar. “New York World. Yes, yes, that was it.’

Chong, his ancient brown eyes peering out from behind wire-rimmed bifocals perched on his nose, examined the reporter sitting across the bar from him.

“You American?” he asked me. I nodded.

“You know something? You’re the first American journalist to come in here since 1937. You work for New York World, too?”

“The Chicago Tribune,” I answered. “The New York World died a long time ago.”

“You come to write about the war, right?” Chong asked. I nodded again.

”There had been some trouble just before that other reporter showed up,” Chong said, recharging his memory cells with a shot of vodka. “Some peasants up north had shot a couple of soldiers. There was talk of another rebellion like the Matanza.” (The Matanza, or “slaughter,” had occurred in 1931 and 1932, when some 32,000 men, women, and children were killed by government forces after an ill-fated uprising by the Trotskyite Indian named Farabundi Marti).

“People were still very excited about it when I came here in 1937,” Chong said, igniting an ancient pipe.”But this American journalist was not. He said Americans didn’t care about little revolutions in little countries.”

Then, eyeing the reporter before him, Chong said, “I guess Americans think differently now, eh?”

Indeed, they do. The little unimportant banana republic visited so long ago by the New York World reporter is suddenly front and center in the eyes of American foreign policymakers.

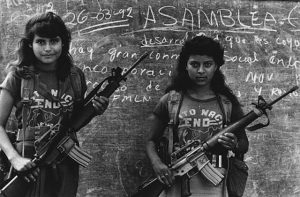

Today, the whole world is watching to see how the United States handles itself in a revolution pitting left-wing guerrillas of the FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front) against the four-man civilian-military junta of President José Napoleón Duarte, backed by Washington.

And unlike 1937, when just one American reporter wandered into town to take a quick look around, San Salvador today is a city overrun with journalists from all over the world.

Most stay at the 235-room Camino Real Hotel, which has evolved into an unofficial media headquarters for anyone covering the hostilities here.

Besides a well-stocked bar, where foreign correspondents tend to gather evenings in clusters to discuss (well, argue) solutions to El Salvador’s problems, the Camino Real offers a government-run telex room for filing stories and messages.

It is not just camaraderie and the dubious benefits of flock journalism that lure journalists to the Camino Real – It Is safety.

“This is the hotel for the International Press,” explained William, the head bellhop. “Neither the left nor the right would be so stupid as to attack this hotel. This is neutral territory.”

Most journalists feel a little naked in El Salvador. Since the fighting began in 1980, five foreign correspondents and photographers have died – not to mention the two dozen or more El Salvadoran journalists who have been tortured or murdered. Conversations in the Camino Real bar tend to be sprinkled with bravado and twists of gallows humor as reporters attempt to put such things out of their minds the way they have always done in war–just as we did in Vietnam and Cambodia.

Except that in the Camino Real bar, Vietnam and Cambodia are taboo subjects. Most of those covering the war in El Salvador, it seems, did not work in Southeast Asia, and there is a perverse, albeit unnecessary, need on their part to convince Vietnam-era reporters that this war is more dangerous than their war.

There is indeed something much more ominous about this conflict, with its constant beheadings, mass murders, and disappearances.

But it is impossible to apply a Bo Derek kind of scale to war. People get blown up. They lose arms, legs, feet, and hands. They die. Who is to say El Salvador rates a ten on the danger scale while Nicaragua, Angola, and Cambodia are only 8s? Such comparisons are not only absurd; they are obscene. Suffice it to say that thus far, El Salvador, with its 30,000 dead, is still far from the 3 million Vietnamese (North and South) soldiers and civilians killed in Vietnam (as well as 58,220 Americans and 105 journalists).

There does seem to be something about El Salvador’s tragic conflict that makes you look over your shoulder a lot, however.

Perhaps it’s that there are so many fanatic fringe elements in this New Jersey-sized nation of five million running around flaunting machine guns, machetes, and machismo.

Right-wing death squads armed with razor-sharp machetes and rifles roam the city streets looking for “subversives.”

Left-wing guerrillas blow up somebody’s house or place of business just about every night. And out on the streets, you learn to examine every car that passes you for the barrel of a rifle or pistol pointed at your belly.

“I don’t think El Salvador has ever been more unhealthy,” said Chong, relighting his pipe. “People don’t come to my place after eight at night anymore because they are afraid somebody is going to throw a bomb through the door. People are scared. I’ve never seen them so scared.”

Outside the Canton China Bar and Restaurant, three government soldiers with semi-automatic rifles slung over their shoulders stood on the corner talking. Chong watched them for a moment.

“When I left China, it was during the Japanese occupation of Manchuria,” he said. “The war was terrible. I wanted to find a peaceful place to live, so I came to Central America. What a mistake. Of course, I’m too damned old now to care. But sometimes, when I see bodies in the streets with their heads chopped off, I think I should have stayed in China.”

(POSTSCRIPT: More than 75,000 civilians died at the hands of death squads and government forces, and guerrillas killed another 4,000 during the civil war in El Salvador (1980-1992). Three well-known atrocities punctuated the 12 years of violence: the 1980 assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero that sparked the conflict, the rape and murder of three American Maryknoll Nuns and a lay missionary that caused international outrage, and the 1989 Jesuit Massacre that finally compelled the international community to intervene. Some 550,000 people lost their homes, and another 500,000 fled the country as refugees during the war. In 1992, the Chapultepec Peace Agreement was signed by the combatants in Mexico City, formally ending the bloody conflict.)

–30–

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. “It’s free—what a deal!” If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, simply enter your email in the notifications box to sign up:

https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent.

You can also find my commentaries on Substack at https://ronyates.substack.com/ and the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us.

Please feel free to comment: We genuinely love hearing from you!

Ron, I knew you’d been in Central America, but I didn’t realize you were there during the same period I lived there. Having been involved in the wars there, I’d truly love to read the book you surely have in you about those times. Break out your old Olivetti Lettera 32 portable and let the pounding begin.