This is a post I shared a couple of years ago. It deals with how much different life was in the distant and not-so-distant past–something of which anybody who writes historical fiction constantly needs to be aware. Enjoy!

When I taught journalism and writing classes at the University of Illinois, it saddened me to realize that my students had such little knowledge of history.

I didn’t blame my students so much as I blamed their K-12 schools for sending them into the world with little if any appreciation for the past and how it shaped today’s world. Instead of learning American and world history, I guess they were indoctrinated with Critical Race Theory, the debunked 1619 Project and a plethora of other classes that focused on modifying and amending history to placate the political correctness police and to suit 20th and 21st-century sensibilities and mindsets.

I was amazed at how many students assumed that the world they lived in today was always this way. Most thought the modern conveniences we take for granted today were always there–just made from different materials or designed differently.

When I revealed to students how different life was in 1905, most were stunned.

I pointed out that in 1905 average life expectancy in the U.S. was 47 years; that only 14 percent of the homes in the U.S. had a bathtub; that only 8 percent of the households had a telephone; that 95 percent of all births took place at home; that 20 percent of adults couldn’t read or write; that only 6 percent of all Americans graduated from high school; that marijuana, heroin, and morphine were all available over the counter at the local corner drugstores; and that there were only 230 reported murders in the entire U.S. you could hear a pin drop.

Those facts alone spurred some students to learn more about life in the past.

For me, an author of action/adventure and historical novels, visiting the past is not an option. It is a requirement. How can you write a book set in the 19th or 18th Centuries without understanding what life was like for the characters you create? The answer: you can’t.

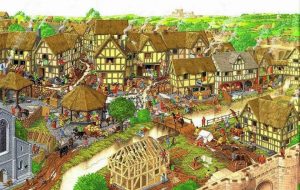

One semester, while teaching my class, I came across some fascinating facts about life in England during the 16th Century. I am sure it mirrored life in 1500’s France, Germany, Italy, and other European countries.

I don’t know who the author is when it was written or even how accurate it is, but when I shared it with my students, eyes widened, and jaws dropped. Here it is, and my everlasting thanks to the person who wrote this.

The 1500’s IN ENGLAND

The next time you wash your hands and complain because the water temperature isn’t just how you like it, think about how things used to be.

Here are some facts about the 1500s, otherwise known as the middle ages:

Most people got married in June because they took their yearly bath in May and still smelled pretty good by June. However, they were starting to smell, so brides carried a bouquet to hide the body odor. Baths consisted of a big tub filled with hot water.

The man of the house had the privilege of the clear, clean water, then all the sons and men, then the women, and finally the children — last of all the babies. By then, the water was so dirty you could lose someone in it–hence the saying, “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

Houses had thatched roofs — thick straw, piled high, with no wood underneath. It was the only place for animals to get warm, so all the dogs, cats, and other small animals (mice, rats, and bugs) lived on the roof. When it rained, it became slippery, and sometimes the animals would slip and fall off the top–hence the saying, “It’s raining cats and dogs.”

There was nothing to stop things from falling into the house. That posed a real problem in the bedroom where bugs and other droppings could mess up your nice clean bed. Hence, a bed with big posts and sheets hung over the top afforded some protection. That’s how canopy beds came into existence.

The floor was dirt. Only the wealthy had something other than dirt, hence the saying, “dirt poor.” The rich had slate floors that would get slippery in the winter when wet, so they spread thresh on the floor to help keep their footing. As the winter wore on, they kept adding more thresh. Sometimes, the thresh would start slipping outside when you opened the door. The occupants placed a piece of wood in the entryway to hold back the thresh–hence, a “thresh-hold.”

People cooked in the kitchen with a big kettle that always hung over the fire. Every day they lit the fire and added things to the pot. They ate mostly vegetables and did not get much meat. They would eat the stew for dinner, leaving leftovers in the pot to get cold overnight and then start over the next day. Sometimes the stew had food in it that had been there for quite a while–hence the rhyme, “peas porridge hot, peas porridge cold, peas porridge in the pot nine days old.”

Sometimes they could obtain pork, which made them feel quite special. When visitors came over, they would hang up their bacon to show off. It was a sign of wealth that a man “could bring home the bacon.” They would cut off a little to share with guests, sit around, and “chew the fat.”

Those with money had plates made of pewter. Food with a high acid content caused some lead to leach onto the food, causing lead poisoning and death. This happened most often with tomatoes, so for the next 400 years, tomatoes were considered poisonous.

Most people did not have pewter plates, but trenchers, a wood piece with the middle scooped out like a bowl. Often trenchers were made from stale paisan bread, which was so old and hard that they could use them for quite some time. Trenchers were never washed, and worms and mold often got into the wood and old bread. After eating off wormy moldy trenchers, one would get “trench mouth.”

The bread was divided according to status. Workers got the burnt bottom of the loaf, the family got the middle, and guests got the top, or “upper crust.”

Lead cups were used to drink ale or whiskey. The combination would sometimes knock them out for a couple of days. Someone walking along the road would take them for dead and prepare them for burial. They were laid on the kitchen table for a couple of days, and the family would gather around and eat and drink and wait and see if they would wake up-hence the custom of holding a “wake.”

England is old and small, and they started running out of places to bury people. So they would dig up coffins, take the bones to a “bone-house,” and reuse the grave. When reopening these coffins, one out of every 25 coffins was found to have scratch marks on the inside, and they realized they had been burying people alive.

Somebody came up with the idea of tying a string around the wrist of the corpse. They then ran the line through the coffin up through the ground and tied it to a bell. Someone would have to sit in the graveyard all night (the “graveyard shift”) to listen for the bell. Thus, someone freshly buried could be “saved by the bell.”

As I mentioned earlier, I have no idea how accurate any of this is, but it makes sense. (However, I always thought “saved by the bell” was a boxing term in which a fighter who had been knocked to the canvas was not counted “out” if the bell ending the round sounded first).

But what do I know? I still believe in King Arthur, Sir Lancelot, Queen Guinevere, and the quest for the Holy Grail–not to mention fire-breathing dragons.

A confession: I only believe in fire-breathing dragons after too much Kaw River Coffin Varnish, otherwise known as grandpappy’s corn squeezin’.

[If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign up for notifications box on the right side of this post or at: https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent You can also find my commentaries on the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us. And please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!]

Great etymology lesson, Ron. I’m not sure about the accuracy, but these accounts make for a much more interesting discussion that the “I-don’t-know” response I recently gave when asked about the origin of the term “graveyard shift.”