At the request of a faithful follower, today I am re-posting a column that appeared a while back in The Economist, one of the U.K.’s most prestigious magazines. Written by an unnamed foreign correspondent, it takes a sardonic and self-effacing view of foreign correspondents by suggesting that Harry Flashman, Victorian England’s foremost rotter, would have made a great journalist. As with all satire, there may be more truth here than we hacks care to admit. Enjoy.

The Cad as Correspondent

From

The Economist

REBELS had captured the dam that supplied electricity to Kinshasa and turned off the lights in the Congolese capital. Now they were marching on the city. Panic reigned. Pro-government thugs were going around lynching suspected rebel spies. Some they hacked to death. One, they tossed off a bridge and shot as he bobbed in the river.

A city under siege, full of power-drunk kids with Kalashnikovs, is no place to be. Your correspondent was there and feeling frightened. Which reminded him of one of the great cowards of English literature. He asked himself: in this situation, what would Flashman do?

For readers who have not yet met him, Flashman was the villain of “Tom Brown’s Schooldays,” a pious novel about life at a British boarding school published in 1857. The author, Thomas Hughes, portrayed him as a bully who roasted small boys over open fires but ran away sniveling from anyone bigger than him.

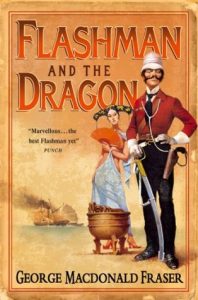

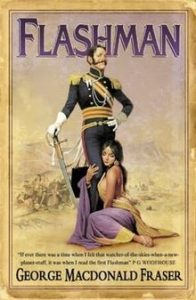

A century later, a Scottish journalist called George MacDonald Fraser wondered what happened to Flashman after he was expelled from school. He answered his own question with a series of wickedly comical historical novels. In Fraser’s telling, the adult Flashman was every bit as horrible as the schoolboy, but through sheer luck and sleazy charm, became one of the most decorated heroes of the Victorian era: Brigadier-General Sir Harry Flashman, VC, KCB, Legion of Honour, San Serafino Order of Purity and Truth (4th class), etc.

His career took off when, having joined the army because the uniform attracted women, Flashman found himself besieged in a fort in Afghanistan. He feigned sickness to avoid fighting. When all the other defenders were killed or wounded, he grabbed the British flag and, pleading for mercy, offered it to the Afghan warriors surging over the walls.

Just then, a big explosion marked the arrival of a British relief force. Flashman was found unconscious, draped in the flag, and surrounded by dead Afghans. Everyone assumed he was defending the colours, not surrendering them, and he won the first of many medals.

Morally, it would be hard to find a worse role model. Over the course of 12 books, Flashman bullied underlings, betrayed friends, cheated on his wife Elspeth, and stabbed in the back anyone who blocked his escape route. Yet there is much that this fictional Victorian rotter can teach modern reporters. Though he was leery of journalists (“tricky villains, especially if they work for the Times”), he would have made an outstanding one.

Flashman’s first instinct was for self-preservation. This is a useful (and underrated) trait for journalists. Had he been stuck in Kinshasa in August 1998, Flashman would have headed for the best-guarded hotel and hung out in the bar by the swimming pool. That is what your correspondent did, and it proved an excellent policy.

The beer was refreshing, the brochettes de boeuf delicious, and the conversation highly informative. All the power brokers, spies, moneymen, and diplomats passed through. By listening to them, your correspondent gleaned a fuller picture of what was going on than if he had ventured out to the front line, which would have involved a lot of hiding in ditches and trying unsuccessfully to figure out who was shooting at whom.

Hang back from the shooting, and you often get a better view. During the Crimean war of 1853-6, Flashman used all his wiles to hang back, describing the campaign with colour and precision from safe hilltops. Unfortunately for him, he was then caught up in the most foolhardy maneuver of the entire war.

His horse bolted towards the Russian cannons, causing Flashman unwillingly to race out ahead of the Charge of the Light Brigade. British newspapers interpreted this as “Flash Harry” up to his usual heroics.

Your correspondent has never galloped into a Valley of Death, but he has occasionally blundered into sticky situations. Once during the civil war in the Ivory Coast, he ran into a rebel roadblock—a heap of branches and a broken fridge with a cow’s skull on top. The youngsters manning it were stripped to the waist, armed with rocket-propelled grenade launchers, and drunk at 10.30 in the morning.

Flashman, faced with superior firepower in unsteady hands, would have smiled, made himself pleasant to his captors, and tried to buy time. That is what your correspondent did, swigging Kou Tou Kou (a fiery spirit distilled from palm wine) out of a shared plastic jerry can. Eventually, he was rescued by a French army officer, who persuaded the rebels that journalists are not spies.

Modern reporters use all sorts of methods to stay safe. They hire fixers. They go on “hostile environments” courses. They send back a barrage of WhatsApp messages describing where they are. None of this is as effective as Flashman’s nose for danger and intense desire to avoid it. Nor can any course teach his genius for getting out of it. Which is probably just as well: throwing one’s lover off the back of a sled to lighten its load and escape pursuing Cossacks is hardly cricket.

Flashman also immersed himself in the local culture. He picked up foreign languages absurdly quickly. By the end of a long career, he was fluent in nine and could rub along in another dozen. He never learned much in a classroom—Latin and Greek bored him senseless. Rather, he learned by listening to native speakers and catching the rhythm and feel of their dialect.

Usually, he did this in bed. Tall, handsome, and effusively whiskered, Flashman was successful with women from a wide variety of cultures. Not all ended up hating him. On one occasion, to pass the time in a dungeon in Gwalior in India, he tried to count his conquests and arrived at a figure of 478. That was in 1857 when he was only 35; he lived to 93.

Speaking multiple languages often saved his skin. Locked up during the Second Opium War, he was the only British prisoner who understood that their Chinese jailer planned to execute one of them. Asked to translate, he lied that the jailer planned to send one of them with a message to the British and French forces besieging the town. Eager for freedom, a soldier who was blackmailing Flashman was pushed to the front—and was conveniently beheaded.

In some ways, being a scoundrel made Flashman a better reporter

A good foreign correspondent will network with powerful people, the better to understand the motives behind important policies. Flashman rubbed shoulders with Wellington, Lincoln, and Bismarck (though Bismarck loathed him and tried to have him killed). His accounts add fistfuls of spice to the historical record.

Indeed, the Flashman Papers can be useful background reading during reporting trips. It was thanks to Flashman that your correspondent understood when visiting the Summer Palace in Beijing the scale and scandal of its destruction by British troops in 1860. When covering a flood in Madagascar, he could find no better short history of the island than Flashman’s Malagasy adventures. And Flashman would have chuckled to learn that lotharios are now known there as bananes flambés, after a popular dessert.

The Flashman Papers purport to be written by Flashman himself—the secret, honest memoir of a garlanded rogue, discovered in a Leicestershire saleroom in 1965 and “edited” by Fraser, with helpful historical footnotes. The books are so well researched that, to naïve readers, they can appear genuine. When “Flashman” was first published in America, about a third of the 40-odd reviewers took it at face value. One called it “the most important discovery since the Boswell papers”. Fraser laughed till it hurt.

Strenuous research (Fraser was a keen amateur historian) and dollops of first-hand observation (he was an energetic traveler, too) are the raw materials of great journalism. To this, Fraser added a crackling prose style and a gift for storytelling. As an observer, Flashman was often caustic but never blinded by the pieties of his age. He believed neither in the civilizing mission of the British Empire nor in the myth of the noble savage. So whether he was observing Englishmen, Sikhs, or Zulus, he recognized fools, heroes, and charlatans for what they were.

In some ways, being a scoundrel made Flashman a better reporter. Many modern correspondents tend to preach. This quickly becomes tedious. Journalists who profess outrage at every minor politician’s off-colour remark soon run out of words to describe real outrages.

Flashman did not have this problem. He was callous and made no effort to pretend otherwise. This made his prose more convincing, for he let the facts speak for themselves. On the rare occasions when he was moved to make a moral judgment, the effect is electrifying. One such instance occurred when he was press-ganged onto a slave ship, where he saw Africans branded, chained, and crammed below decks.

“The crying and moaning and whimpering blended into a miserable anthem that I’ll never forget, with the clanking of the chains and the rustle of hundreds of incessantly stirring bodies, and the horrible smell of musk and foulness and burned flesh. My stomach doesn’t turn easily, but I was sickened…when you’ve looked into the hold of a new-laden slaver for the first time, you know what hell is like.”

He admitted that if someone had approached him in his London club and offered him £20,000 to authorize a shipment of slaves, he would have taken the money. Out of sight, out of mind: this was also the attitude of many of his respectable contemporaries to buying slave-made sugar or cotton. Fraser did not need to remind readers that Flashman—a sociopath—was, in this respect, little worse than millions of 19th-century British tea drinkers.

Laptop, flak jacket, condoms

Being a foreign correspondent is the most enjoyable job there is. The men and women who are lucky enough to do it today travel the world, meet new people, sample exotic new dishes and grapple with new ideas. Even when it is uncomfortable, it can be exciting. To make the most of a posting, journalists must be open to new experiences and skilled at seeking them out. It helps to have a fat expense account.

Flashman sometimes had no money at all but made up for it with resourcefulness. When fleeing from angry gun-toting slave owners in New Orleans, he crept into the French Quarter and inveigled his way into a luxurious brothel by seducing the madam, who fell in love with him and asked her butler to ply him with fine wine and Cajun delicacies.

Your correspondent had a more austere time in the Big Easy in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina. At one point, he, too, had to beat a tactical retreat from an angry gun-toting homeowner. Alas, with all the hotels in town closed by floodwater, the only place to sleep was in a cramped, sweaty caravan with half a dozen other hacks, some of whom snored.

Whenever your correspondent visits a place where the ultimate cad once trod—Harper’s Ferry, Isandlwana, even west London—the relevant passage from the Flashman Papers comes easily to mind. Such memorability sets a standard that journalists rarely match. Most of his own work, he knows, is written in haste and soon forgotten.

As he writes this, he is about to head for Afghanistan, where Flashman earned his first laurels. In his luggage will be the first “Flashman” on his iPad. And at the first whiff of danger, he will bolt.

This article appeared in the Christmas Specials section of the print edition of The Economist under the headline “The cad as correspondent.”

[If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign up for notifications box on the right side of this post or at: https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent You can also find my commentaries on the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us. And please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!]