During my 27-year career with the Chicago Tribune, I rubbed elbows with some of the best journalists in the world.

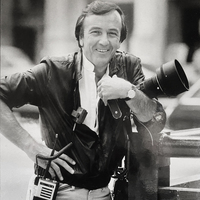

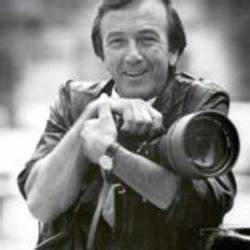

Anthony “Val” Mazzenga, my friend and colleague at the Tribune, was one of those.

Val passed away on December 2, and with his death, one of the greatest careers ever in the tough, competitive world of photojournalism was lost to the ages.

Did I call Val a “photojournalist?” To be perfectly honest, Val would have hooted at that description. He preferred to be known as a “shooter”—a news photographer. He didn’t have much use for such ornate and highfalutin monikers as “photojournalist.”

Indeed, his career stretched back to the era of those big boxy 4 x 5 Speed-Graphic cameras some newspaper photographers in Chicago schlepped around until the late 1960s.

Unlike many of today’s news photographers, Val didn’t study photojournalism in college. Val learned the craft of news photography from the ground up, working first as a 15-year-old Tribune copyboy.

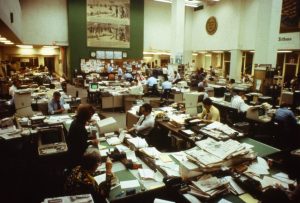

As he ran copy and photos between reporters and photographers and their respective news desks, Val discovered something significant about himself: He had both an affinity and a talent for the “visual word,” i.e., photography. It wasn’t long before he managed to move into the Tribune’s sprawling photo lab and then into a job as a Tribune photographer.

However, there was a price for joining the Tribune’s photo staff. He had to give up his first name.

“We have too many Anthonys and Tonys around here already,” the chief of photographers told him. “What’s your middle name?”

Mazzenga’s middle name was Val, and from that point on, that’s how he was known.

Val was fortunate to find his way into a job he would eventually excel at because life could have taken him in a much different direction.

Growing up on Chicago’s West Side in what was known as “Little Italy,” Val once told me he almost ended up like a lot of young Italian-American kids on Chicago’s mean streets, “stealing cars, running numbers, and working as a bag man for the mob.”

Instead, Val’s career path took him in another direction, and on the way, he became one of the most storied photographers in Chicago newspaper history.

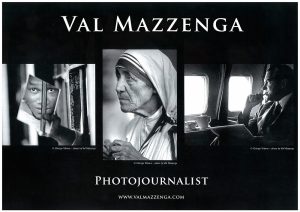

His photographs won more than 200 awards, including five Beck Awards—the Chicago Tribune’s highest editorial accolade, making him one of the most honored photographers ever at the Tribune. Val’s work was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize six times, and he was inducted into the International Press Corps Hall of Fame in June 2008.

His work was exhibited nationwide, including an exhibition at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. At that show, visitors viewed Val’s prize-winning photo essays of Mother Teresa and President Nixon—the latter during an exclusive flight on Air Force One with the president between Chicago and Washington, D.C.

For me, however, I will remember Val not for his many well-earned accolades but for the many assignments we worked together in places like Peru, Mexico, Vietnam, Brazil, Hong Kong, Colombia, Thailand, Chile, and Argentina, to mention just a few of our reportorial destinations.

However, our collaboration didn’t begin with those significant overseas assignments. It began one night in 1972 when we were both working the late night shift in the Tribune’s cavernous newsroom.

A few of us were sitting at the City Desk, engaged in small talk when a call came in over the Chicago Police scanner saying there was an officer-involved shooting with casualties in a bar on the near northwest side of the city.

“Val, you and Yates better get over there,” the night city editor barked.

I recall it was a typical Chicago winter night, and it was cold as hell.

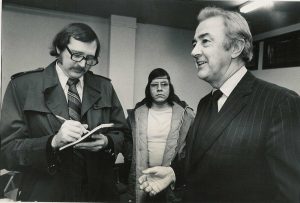

Val grabbed his camera, and I grabbed my notebook. I threw on my trench coat, and we dashed out the back door of Tribune Tower and climbed into Val’s car. Up until that night, Val and I hadn’t talked very much. We certainly didn’t know one another well. I had only been at the Tribune for about two years at that point, while Val was a seasoned professional.

It took us only 10 minutes to get to the crime scene because we used lower Wacker Drive—Chicago’s labyrinthine underground network of roadways known mostly to delivery vehicles, reporters, and photographers. Val parked about a block from the bar, and we walked up a short hill on a sidewalk lightly dusted with snow.

When we got to the bar’s door, a uniformed cop inexplicably stepped aside, and Val and I walked right in.

Maybe a little context is required here. In 1972 I was about 6 feet 4 inches tall and weighed about 225 pounds. Since then, I’ve shrunk a half-inch and dropped 25 pounds. The point is, that night, I looked like a linebacker. Val, meanwhile, had already mastered a deadpan expression that belied his true calling as a news photographer. I guess the cop figured I was from Area 6 homicide and Val was a police photographer.

So in we went. The place was a mess. Tables and chairs were overturned, and broken glass littered the floor. The bodies of three men—one of them a plainclothes cop—were strewn on a floor awash in pools of dark crimson blood.

At the back of the bar, a woman and a man were seated alone at a table, talking quietly. We rightly concluded the woman was a waitress and the man a bartender.

A knot of detectives was rummaging around the bar marking the location of shell casings and discarded handguns. Others were inspecting the bodies of the three men on the floor. Nobody paid attention to Val and me, so we walked to the back, where the woman and man were seated. On the way, I wondered if the two of us were contaminating the crime scene. It’s quite possible we did.

“What the hell happened here?” I asked the couple, employing my best dispassionate cop’s voice.

“This guy (he pointed at the body nearest to us) and two other guys were sitting at the bar when those two (he nodded toward the other two bodies several feet away) walked in and started shooting.”

I scribbled fervently in my notebook, and Val snapped several photos with his 35 mm F-2 Nikon.

“That’s right,” the waitress said. “They didn’t say a word. Just started shootin.”

We talked a few minutes more with the witnesses, then looked at one another. At that point, Val and I had been in the bar for almost 10 minutes, and we knew it was only a matter of time before somebody asked to see our IDs. So we moved as inconspicuously as possible toward the door.

“You guys leavin?” the cop at the door asked.

“Yeah,” Val answered. “This isn’t our area. We were driving by when we heard the call.”

I nodded in agreement.

“Hell of mess, ain’t it?” the cop said.

“Sure is,” I responded.

Later, we learned that the three plainclothes detectives who had been sitting in the bar were involved in a shakedown of the bar, which was a well-known spot for illegal drug sales. Somebody, possibly a drug dealer, hired the two deceased men sprawled on the floor to eliminate the three cops. Instead, they wound up eliminated.

The two surviving cops were not in the bar when Val and I arrived. They were whisked away, and the official story was that the three cops were targeted because they were cops. No mention of the alleged shakedown.

Val and I hurried back to the Tribune. I wrote my story, and Val developed his film.

“You look more like a cop than most cops do,” Val told me later. “I think that’s why we got into that bar.”

He may have been right, but I think we just got lucky.

Val and I worked on a few other Chicago stories during the next couple of years. Then, in 1974 I joined the Tribune’s foreign staff as Far Eastern Correspondent based in Tokyo. That led to one of the biggest stories in my career as a foreign correspondent—the 1975 fall of South Vietnam to the Communist North Vietnamese. Even though I carried my own Nikon F-2 during the fall of Saigon, I recall wishing that Val had been there with his camera. His photos of that historic event would have put mine to shame.

As I covered other stories in Asia, I often thought of how better my stories would have been had Val’s discerning eye and his prodigious collection of Nikon lenses been along.

Finally, in 1977 Val and I got to work on an international story together. Along with Tribune reporter Dick Longworth, we were assigned to produce a series of stories on every country in South America. Longworth and I divvied the continent, and Val split his time between us, illustrating what would become the Tribune’s Pulitzer Prize Entry for 1978. The Tribune eventually produced a special booklet entitled “South America 1978” that contained all of the stories in the series along with Val’s collection of brilliant photos.

From that point on, Val and I became a kind of de facto team. We worked together in Mexico on a series about Mexico’s oil fields. We produced another series of stories on Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

We followed the cocaine trail from the jungles of Peru to the cartels of Colombia. We ventured deep into the Amazon jungles of Brazil via the Amazon and Rio Negro Rivers. We spent several weeks in squalid Cambodian refugee camps along the Thai-Cambodian border, exposing the human tragedy of the communist Khmer Rouge’s lethal genocidal rule of Cambodia.

There were other assignments that Val did on his own or with other reporters: the mass 1978 suicide in Jonestown, Guyana; the Afghan resistance fighters in Pakistan; starvation in Africa; and the Sikh revolt in India, to name a few.

Our last joint reporting assignment was in 1995 when Val and I returned to Vietnam for a special series on the 20th anniversary of the April 1975 Fall of Saigon. We spent three weeks or so traveling all over what was once South Vietnam talking to dozens of Vietnamese about the war and their lives under the communist regime. Once again, Val’s photography brought the stories I wrote to life.

In 1997, I left the Tribune to join the Department of Journalism at the University of Illinois as Department Head and Professor of Journalism. But that was not the end of my collaboration with Val.

That same year I asked Val to come to the university as a visiting lecturer and spend time with photojournalism students. It was one of best things I ever did. Not only did the students get to see Val’s lifetime of work, but they also got to know him.

“What a great guy,” students would tell me. “And what a gifted photographer.”

Each year thereafter, Val returned for weeklong seminars on photojournalism. In 2003, when the University promoted me to Dean of the College of Media, I made Val an Adjunct Professor of Journalism. He continued his seminars until I left the university in 2009.

Naturally, the students were delighted with the war stories Val told about his many assignments. His wry sense of humor was often on display, such as the tongue-in-cheek lecture he once gave to an Introduction to News Writing class entitled: “How I gave Ron Yates all of his good story ideas!” Ahem.

Okay. So what was so special about working with Val? The answer is multi-faceted.

First, it was Val’s street-wise ability to think on his feet. No matter the obstacle, he never let it get in the way of “making the picture,” as he used to say.

Val also had an uncanny ability to communicate with anybody, no matter what language was spoken. Did Val speak a plethora of foreign languages? Hell no. If anything, Val spoke Chicago-ese with a smidgen of Italian tossed in at pertinent points.

Val didn’t need to communicate with people verbally. He “talked” to them with his personality, his eyes, his smile, and a visceral, authentic affability. Believe me, working with someone like that makes life a lot easier when you are on the road.

That doesn’t mean Val liked everybody he met. Absolutely not. Val was an astute detector of shall we say, “bull slingers.” He could spot a phony a mile away. That’s when he might fire off a few choice Italian broadsides. Some of his favorites? Bacha ma Culo (kiss my ass), Sfigato (loser), Cazzata (bullshit).

Val did not suffer fools. If you were a good reporter, he enjoyed working with you. If you weren’t, that was likely the first and last time you worked with Val. He was a professional through and through, and he demanded that any reporter he worked with be the same.

Val worked with some of the best reporters the Tribune ever fielded. The Late Ann Keegan was one of them. Like Val, she hated phonies. They also worked together overseas and produced some magnificent stories.

Mike Sneed was another. During her time at the Tribune, she and Val traversed the planet producing some great journalism. After Mike left the Tribune and became a columnist for the Sun-Times, she and Val remained friends.

Val also worked with two-time Pulitzer winner Bill Gaines, who I brought to the University of Illinois as a professor of journalism specializing in investigative reporting. There were others too. Investigative reporters John O’Brien, Ron Koziol, Bill Curry, George Bliss, and Bill Jones, who would later go on to become the Tribune’s managing editor. I’m sure I am forgetting many other great reporters, so if you aren’t on that list, I beg your pardon.

You don’t work as closely as Val and I did together without getting to know one another exceedingly well. The two of us almost always saw eye to eye when it came to pursuing a story or working on an assignment, and if we didn’t, we both knew the art of compromise.

My objective was to get the story. Val’s was to get the pictures. The two goals were not mutually exclusive. But when they were at odds, we both knew when to concede so we could work together.

That came not only from reciprocal respect but from the trust we had in one another. I don’t believe there was ever a story I didn’t get or a photo that Val missed because we were at variance.

We both loved our work. I recall many times when we were sitting in a restaurant or coffee shop in some far-flung spot, talking about our jobs.

“I can’t believe we’re getting paid to do this work,” I said once when we were having lunch in an open-air restaurant in Aranyaprathet—a village on the Thai-Cambodian border.

Val nodded. “Can I tell you something?” (Val often prefaced a comment with that question.) “I think I would do this work even if the Tribune didn’t pay me. We have the best jobs in the world.”

Amen, brother.

Val was not only my professional colleague, he was my good friend.

I will miss him until the day I also join the Great Majority.

After that, who knows? Maybe God will give the two of us an assignment covering the universe.

[If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign up for notifications box on the right side of this post or at: https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent You can also find my commentaries on the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us. And please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!]

Wonderful tribute for a true friend of yours.

Thanks, Joe, Val was a true original!