Forty-nine years ago, I was on a U.S. Navy ship headed to the Philippines. It was May 1, and a couple of days before, I was evacuated from a place called Saigon (known today as Ho Chi Minh City) as it fell to Communist North Vietnamese troops.

April 29, 1975, is a day I will never forget, not only because I wasn’t sure if I would get out of Vietnam in one piece but because I still consider it one of the greatest betrayals in American history–the disastrous and shameful exodus from Afghanistan in 2021 notwithstanding.

In Vietnam, thousands of Vietnamese who had worked for and with the United States to keep South Vietnam from being conquered and assimilated by Communist North Vietnam were left behind as America abandoned them to concentration camps and worse.

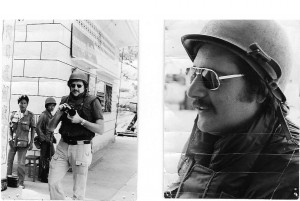

At the time, I was the Chicago Tribune’s Far Eastern Correspondent based in Tokyo. Two years after the spurious Paris Peace Accord was signed, I went to South Vietnam and Cambodia to report on both countries.

Today, I am sharing with you my account of that harrowing, panic-filled 24-hour period between April 29-30, 1975, when a ten-year-long war that some have called America’s “lost crusade” came to a frantic and ignominious end. If, like millions of other Americans, you watched televised accounts of our chaotic and dishonorable exodus from Kabul, Afghanistan, you will have some idea of what it was like leaving Saigon 49 years ago.

I post about that event every year on or near the anniversary of Saigon’s fall because it was a major episode in American history, and I was there covering it. I also believe that, as Americans, we need to remember history and remember it accurately. Today, there is too much partisan distortion of America’s history in our K-12 schools and universities a la Critical Race Theory–a dishonest, Marxist-inspired revisionist retelling of America’s unique story.

So, if you want to know what really happened on the last day of America’s involvement in Vietnam, please read on.

As an FYI, I have credited my photos with my name. However, I have also used several other photos that I took from The Internet. Most of those are not credited because they were without a credit line, and I was not able to provide attribution. I apologize for that and ask for your indulgence if any of these photos are yours.

Leaving Saigon, April 29-30, 1975

During that frantic final day, 1,373 Americans, 5,680 Vietnamese, and an exhausted and ailing American ambassador with the American flag folded under one arm and his pet poodle under the other would flee a land infamous for its coups d’état and its Byzantine cabals—a stunningly beautiful place of soaring green hills, lush forests, vast rubber plantations, and fertile rice paddies that had become a political and military swamp for several American presidents.

Most Americans have subsequently concluded that what was then the longest war in this nation’s history was also the first war America ever lost. However, as a former North Vietnamese colonel told me several years ago, one of the great ironies of Vietnam is that the American military was never defeated in any battle of consequence in Vietnam.

“You lost the war in the cities and villages of America, not on the battlefields of Vietnam,” Col. Ba Thang, political commissar of the Saigon Gia Dinh Special Action Unit, told me. “We could never hope for a military victory against such a formidable foe. Our strategy was to survive, to make the war last so long that you Americans would eventually tire and go home. That is what happened. We divided you politically and sapped your will to fight a war in a country few Americans had ever heard of or cared about.”

Indeed, while the specter of Vietnam still haunts us today, in the 1960s and 1970s, it divided the nation like nothing since the Civil War. In some ways, it continues to do so.

References to American involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan as America’s “new Vietnams” are consistently seen and heard in the news media. The phrase “no more Vietnams” adorns placards at nearly every demonstration against any U.S. military involvement, and one even hears references to “the light at the end of the tunnel,” the phrase used in the 1960s by former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara to describe U.S. progress toward winning the war in Vietnam.

McNamara’s pet phrase was far from my mind 49 years ago when a barrage of 122 mm rockets slammed into Saigon. It was a little after 4 a.m. on April 29, 1975, when I was jolted awake in my second-floor room of Saigon’s four-story French colonial-era Continental Palace Hotel. As I sat upright in my bed, I realized it was oppressively hot and strangely quiet after the initial explosions.

Then I realized why. The old window air conditioner had stopped its moaning and coughing. There was no electricity. The North Vietnamese had hit one of Saigon’s power plants—a common occurrence during the past few weeks. I lit one of the dozen or so candles I always kept ready and looked up at the ceiling.

The gecko lizards stopped chasing after mosquitoes and retreated down the walls. Cockroaches the size of credit cards were scampering into the cracks of the ruby floor tiles. Even the rat that regularly patrolled my room was gone (I had named the rat General Giap, after the architect of North Vietnam’s military campaign).

I wondered if what I had heard had been thunder. April 28th had been a day of thunderstorms with lightning flashing over the city. Then, a few moments later, the unmistakable metallic sound of a 122 mm rocket shrieked through the thick, humid night air and exploded nearby. This time, chunks of ancient plaster fell from the ceiling, and the walls of the 100-year-old hotel shuddered.

That was not thunder. These were the first rockets to hit Saigon since April 27, when one slammed into the roof of the Majestic Hotel overlooking the Saigon River a few blocks away, killing a hotel porter. Later that same morning, another rocket smashed into Saigon’s bustling Ben Thanh Market, killing more than a dozen people.

I jumped from the bed, scampered barefoot over the cold crimson tiles to the small balcony overlooking Lam Son Square, and threw open the French windows. Before me, looming in all its hulking alabaster majesty, was the old National Assembly Building and, beyond it, the high-rise Caravelle Hotel. Both were intact.

To my right, where Le Loi Street bisected Tu Do Street, several South Vietnamese home guard members, with red rosettes in their buttonholes identifying them as loyalists, were firing their old M-1 carbines. For the past several weeks, home guard troops, who were primarily teenagers, had patrolled the streets by day and slept on sidewalks wrapped in ponchos at night.

As I looked down at the home guard, bullets whined through the dank night air and ricocheted off nearby buildings. I ducked as several rounds slammed into the white façade of the hotel. During the past several months, I had gotten to know several of these home guard militias. Their job was to enforce Saigon’s nighttime curfew. I paid them to escort me after curfew to the Public Telephone and Telegraph Office so I could telex my stories back to the Tribune.

“What are you shooting at?” I yelled.

“V.C., beaucoup V.C.,” a 17-year-old named Nha shouted back.

“Where?”

“They everywhere…you better hide.” Then Nha, who was usually wasted on Vietnamese “33” beer by this time, shrieked with laughter. “Không Quan trọng!” (It doesn’t matter). We kill all number ten V.C.”

Yeah, I remember thinking, if you don’t kill everybody else in the city first. Nha lifted his rifle and fired several more rounds into the air. I had seen Nha in action with his M-1 carbine during our after-curfew hikes to the PTT office. He often amused himself by blasting away at the enormous rats that roamed Saigon’s deserted streets after the cyclos and ancient smoke-belching Renault taxis had stopped running for the night.

I retreated into my room. In the distance, there were more heavy explosions—what sounded like 80 mm mortar rounds and 130mm heavy artillery hitting Tan Son Nhut, Saigon’s main airport some 7 miles away. As I dressed, the temperature was approaching 90 degrees, and the sun wasn’t even up. I decided to forgo what would have been a cold shower. I needed to get downstairs to see what was going on.

Peace With Honor?

Was this it? I can recall thinking. Is this the end? As it turned out, America’s disastrous crusade in Vietnam was indeed over. And this was how it would end: not with honor, as one president had suggested, but in disgrace, humiliation, and chaos.

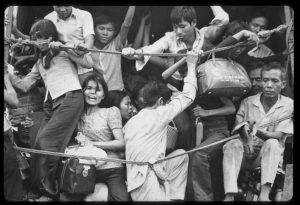

Even though the city was now under a 24-hour curfew, for much of that final day, some 20,000 terrified, shrieking Vietnamese—many of them former U.S. government employees—would surround the American Embassy, pleading with Marine guards to allow them inside the 10-foot walls so they could board the choppers that would take them to the armada of 44 American ships waiting off the Vietnamese coast.

Some would make it over the walls and onto the helicopters. But only some. Most would be held at bay by U.S. soldiers—former allies—who pointed M-16s at them, cursed them, pounded their clawing fingers with rifle butts, and threatened to blow their heads off. I can still hear the voices of American embassy officials and their Vietnamese interpreters shouting: “Không ai sẽ bị tụt hậu!” (No one will be left behind) at the frantic throng outside the Embassy compound.

It was a scene that still saddens me today—one that made me ashamed to be an American, not because we were leaving in abject defeat but because we were betraying thousands, if not millions, of Vietnamese who believed our promises of a free and democratic Vietnam if they supported our policies.

I arrived in Vietnam from my Tokyo base in January 1975. Except for a few weeks spent in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in late February and early March, I lived in Saigon at the Continental Palace Hotel.

The North Vietnamese push for Saigon began on March 7 in Vietnam’s central highlands. Four days later, the provincial capital city of Ban Me Thuot, 180 miles north of Saigon, fell. A few days after that, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu decided to adopt a plan of “strategic withdrawal,” which, in effect, conceded the northern half of South Vietnam to the Communists and precipitated one of the greatest routs in military history.

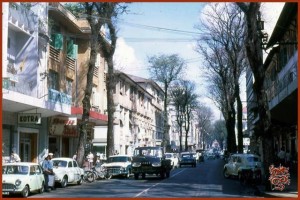

The North Vietnamese controlled almost 75 percent of the country by early April, and a palpable sense of doom enveloped Saigon. The city’s ubiquitous bars, famous for their “Saigon tea,” were mostly empty. Vendors selling “pho” and “cà phê sữa”(beef noodle soup and “white” coffee), beggars, and hundreds of homeless children had all retreated from the streets. While these were ominous signs, I knew the end was near when the Indian tailor on Tu Do Street, where I had gotten shirts made and changed dollars into Vietnamese piastres, began producing North Vietnamese and Viet Cong flags instead of American and South Vietnamese banners.

“It’s the reality of the situation, you see,” he told me one afternoon. “You do what you must do to survive. You press chaps can leave; I cannot. Frankly, I am happy that this nasty affair is finally ending after so many terrible years.”

A Terrible Toll

The official length of the war is generally conceded to have been eight years—from 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson sent in the U.S. Marines, to 1973, when the Paris Peace Accord was signed. However, if you count the first advisers sent to Vietnam by Harry Truman in 1950, America’s involvement in S.E. Asia spanned three decades. About 3.1 million military personnel (including 7,200 women) served in Vietnam during that time.

The human toll was staggering. By the time America’s active involvement in the war officially ended in 1973, it had claimed the lives of 58,183 American men and women. Another 304,000 Americans came home wounded, sometimes physically and sometimes mentally. One of every ten soldiers who served in Vietnam was a casualty.

Also, 105 journalists died covering the war—more than in any other conflict in world history. Several are still missing.

Vietnam was nothing if not intense. For example, Pentagon figures show that the average infantryman in the Pacific theater saw about 40 days of actual combat in four years during World War II. In Vietnam, the average infantryman saw about 240 days of action in one year—a fact directly attributable to the helicopter, which allowed for much more rapid troop deployment.

Then there are the MIAs—the 2,211 Americans still unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, including 1,651 in Vietnam.

The dollar cost of the war: More than $165 billion—a figure that includes the loss of 3,689 fixed-wing aircraft, 4,857 helicopters, and 15 million tons of ammunition.

In Vietnam, the impact of America’s involvement in the war was even more conspicuous: 3 million Vietnamese were killed, including 1 million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers, 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers, and 2 million civilians, according to Vietnam’s Ministry of Labor, War Invalids, and Social Affairs. More than 600,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops were wounded. In comparison, 500,000 South Vietnamese troops were injured, and 2 million civilians on both sides were crippled by mines, artillery fire, chemical defoliants, bombings, and the general mayhem of war.

*************************************

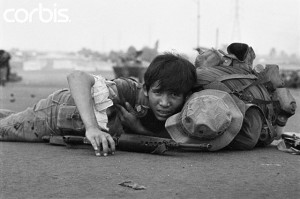

In early April, I had driven my rented jeep to a town called Phouc Hiep and found myself in the middle of a rice paddy along with a handful of other reporters when a firefight broke out between ARVN (South Vietnamese) and North Vietnamese troops.

We broke into a wild run across a vast expanse of dry paddies toward a hamlet when we heard the telltale “thump” of a mortar shell being fired.

“Eat dirt,” someone yelled, and we plunged en masse into a 3-foot-deep irrigation ditch. Seconds later, an earsplitting explosion sent huge chunks of dirt and rock flying through the air and on top of us. We were fully exposed in the middle of a 10-acre chain of rice paddies. The nearest cover was a small river about 300 yards away. We thought about dashing it, but small arms fire from both sides kept us pinned down. We remained there in the muddy ditch for what seemed like hours as bullets kicked up dirt all around us. In fact, the battle lasted only about 15 minutes.

When the shooting subsided, we scampered toward the river, zigging and zagging. When we got there, we paid some farmers who had taken cover along the river bank to ferry us to the other side in their wooden dugout canoes. Once there, we were met with the aftermath of the battle. The bodies of perhaps 15 NVA soldiers were strewn across a field. They had walked into an ambush.

I was making a few notes and photographing the scene when several children from the nearby village emerged and began stripping the soldiers of any valuables they had—watches, rings, shoes. Others were amusing themselves by jumping back and forth over the wire cable that connected several anti-personnel claymore mines to a triggering device. One touch and the mines could have killed six or seven children and anybody else standing within the effective killing range. When detonated, a Claymore sends some 700 steel balls flying in a 60-degree horizontal arc at 6 feet over a radius of 300 feet.

In Vietnam, I wrote in my notebook the war and its instruments of destruction had become a deadly amusement park.

“La Guerre est fini; Saigon est fini!”

On April 20, the provincial capital of Xuan Loc, just 46 miles east of Saigon, fell after holding out for several days against a tenacious siege by NVA troops. The fall of Xuan Loc was a signal for people to proclaim what quickly became Saigon’s epitaph: “La Guerre est fini; Saigon est fini; everything est fini.”

It also sped up the dynamic Saigon rumor mill. One rumor said that Catholics originally from the north would be sent on a death march along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Another story said that Viet Cong soldiers in Da Nang had ripped out the manicured fingernails of prostitutes, prompting a frenzy of fingernail cutting and polish removal among Saigon’s bar girls. Yet another rumor said that unmarried Catholic girls would be forced to marry North Vietnamese war invalids.

The rumors had one cumulative effect: they supported the growing belief that the end was near.

Since early April, several of us had pressed the U.S. Embassy for details of the evacuation—with no result. U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin, who died in 1990, was intent on not creating panic by discussing the possibility of an American departure. Until the last day of the war, he hoped that a negotiated end of hostilities could be worked out. Indeed, two days before, he had gone on Vietnamese television and announced: “I, the American Ambassador, am not going to run away in the middle of the night. Any of you can come to my home and see for yourselves that I have not packed my bags. I give you my word.”

Martin had, nevertheless, sanctioned a low-key evacuation of Vietnamese and Americans called Operation Talon Vise. Two weeks before April 30, Operation Talon Vise evacuated about 37,000 Vietnamese employees of the U.S. government and their families from Tan Son Nhut to Clark Air Base in the Philippines—far short of the several hundred thousand Vietnamese who had worked with the American military assistance command in some way and who ultimately would be consigned to horrific “re-education camps” by the communist conquerors, in some cases for ten years or more.

To ensure that Talon Vise went smoothly, Martin authorized bribes to Saigon police so buses could move through checkpoints without a problem. He also allowed Vietnamese to be smuggled into the American Embassy through a hole cut into the wall of the adjacent French Embassy.

“What a perfect metaphor for this fucked up place,” the late Hunter S. Thompson, covering the end of the war for Rolling Stone Magazine, told me one evening. We were having dinner at the My Canh floating restaurant on the Saigon River. “Lies, deceit, and betrayal. Hey, I think I have the name for my next book.” The “gonzo” journalist then took a long drag on a fat Buddha grass joint and asked if he could ride with me to “the action” the next day.

I dreaded taking Thompson with me because he tended to wander off. I always feared that I would return to Saigon and have to announce that Thompson was captured by the Viet Cong or had stepped on a mine. I didn’t want to be responsible for the death or capture of “Uncle Duke,” the Doonesbury cartoon strip character modeled on Thompson.

“What a thought,” someone said one evening. “If Thompson gets captured, he will get the whole North Vietnamese Army high, and the war will be over tomorrow.”

As it turned out, Thompson left Saigon for Hong Kong long before the evacuation, and Rolling Stone had to send in another reporter to cover the story. “This bull shit is going to last forever. I’ve got rigorous shopping to do,” he told me before leaving for the airport.

Thompson’s assessment notwithstanding, Ambassador Martin did not want to be accused of cutting and running. Until the last few hours, he was convinced there could have been some negotiated, equitable settlement to allow a smooth power transition. It is possible today to forgive Martin for his muddled thinking—especially in light of the revelations contained in the book “In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam” published in 1995 by one of the architects of America’s involvement in Vietnam, former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara.

McNamara’s admission that he and others in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations knew the war was wrong—and even un-winnable—as far back as 1965 but decided to send Americans to fight and die there anyway makes Martin’s diplomatic dithering seem acceptably innocuous.

White Christmas in April

Finally, on April 26, with 16 NVA army divisions converging on the capital from every direction, the U.S. Embassy revealed a unique “evacuation code” that would alert us when an evacuation was imminent.

The code, which would be played over a local U.S.-operated FM station, would be this: A short announcement that said, “The temperature is 105 degrees and rising,” followed by the first eight bars of the song “White Christmas.”

I can recall sitting one evening on the “Continental Shelf”— the open-air veranda of the Continental Palace Hotel (now glassed in and renamed Chez Guido) that overlooks Tu Do and Le Loi streets—when several Japanese correspondents came rushing up to my table.

“How does ‘White Christmas’ go?” they inquired anxiously. I hummed it for them. For the next few days, Japanese and others not familiar with the old Bing Crosby Christmas standard could be seen standing on Saigon street corners, humming the song to one another.

It was one of those droll little moments that punctuated the more considerable agony of the war’s last few hours.

But that humor was all but forgotten as April 29 dawned, and several of us huddled in the lobby of the Continental Hotel listening to the portable UHF receiver an embassy official had given the American press corps.

Over the tiny receiver, we could hear radio traffic between the U.S. Marine contingent charged with guarding the hulking complex of U.S. Defense Attache Office buildings near Tan Son Nhut Air Base called “Pentagon East.”

The radio crackled with a running commentary from the Marine unit assigned to the building as one artillery shell after another slammed into Tan Son Nhut and the American compound.

“The back end of the gym’s been hit!” a Marine shouted into his radio.

“Roger that, Whiskey Joe,” came the monotone reply from the embassy, which was appropriately code-named “Dodge City.”

“My god, control, we’ve got two Marine KIAs.”

“Where are the bodies?” asked the voice from the embassy.

“They’re right here. What should we do with them?”

Then, there was a tremendous explosion, amplified by the small radio.

“Jesus, the ammo dump’s just been hit! All hell has broken loose out here!”

Operation Frequent Wind

A few hours later, Operation Frequent Wind (the name given to the final evacuation) was ordered by President Gerald Ford, and I paid one last visit to my room in the Continental Palace. I had stockpiled a couple of cases of American beer, soft drinks, a variety of PX junk food, and a small library of pirated books.

I found Mr. Phan, one of the elderly hotel concierge staffers, who slept in a small room on the second floor, sweeping my room as if nothing had happened. For almost two months, Mr. Phan, who always appeared in clean white cotton pants and jacket, had cleaned my room, kept me in fresh bottled water, and occasionally sprayed my room in a futile gesture at ridding it of roaches and other critters of the night.

I pressed a wad of Vietnamese piastres into his hand. Then it occurred to me that the money would be worthless in a few hours—indeed, as far as Saigon’s ubiquitous money changers were concerned, piastres had been worthless for the past two weeks.

I had about $500 in cash, and I peeled off $300 and gave it to him.

“Here, this may come in handy, Mr. Phan,” I said. “And please take anything you want from my room,” I suggested that he might want to get out of central Saigon and find a safe place until the fighting and artillery barrage stopped.

He smiled, bowed ever so slightly, and announced: “Thank you, but not to worry, I am V.C!”

Many of us had suspected that a lot of the “boys,” as Mr. Phan and his co-workers at the Continental were called, were probably Viet Cong or V.C. sympathizers. Many journalists stayed at the old hotel because we had heard that the owner paid “war taxes” to the Viet Cong so it would not be targeted for attack.

As we shook hands, he looked up at me and said, “Why do you not stay? Everything will be OK here. It would be much better if you stayed here.”

I explained that the Tribune had ordered me to leave and that I had a baby daughter I hadn’t seen for almost four months.

He nodded. “Yes, yes, maybe it better you go now.”

It was the last time I would ever see Phan, who was in his 70s at the time. When I returned in 1985 for the 10th anniversary of the war’s end, the staff at the Continental Palace informed me he had passed away in 1982.

By 10 a.m., a small army of American, European, and Asian correspondents lugging typewriters, sound equipment, suitcases, and shoulder bags left the Continental in a single silent file. We had been told to make our way to a point six blocks away near the Saigon River.

As we trudged down Tu Do Street, ARVN soldiers, and home guard units watched our ragtag formation menacingly. In the distance, we could hear the constant explosion of artillery and mortar shells as they slammed into the city’s suburbs.

“I’m Sorry . . . Sorry For All of This.”

“You leave now?” Nha, the home guard soldier, asked me as we slogged toward the river. His M-1 carbine was slung over his back, and for the first time since I had known him and his small squad of home guard soldiers, he seemed genuinely terrified of what the next few hours would bring.

“Yes, we leave now,” I said sheepishly. Then, for some reason, I said, “I’m sorry . . . sorry for all of this.” I was ashamed—ashamed that I was leaving and ashamed of my country. I still am.

“Không sao, nó không quan trọng!” (Never mind, it doesn’t matter), Nha said. “You come back someday.” He was right, of course. I would return in 1985 and again in 1995 to witness the 10th and 20th anniversaries of the fall of Saigon.

Finally, we arrived at our evacuation point: a spot facing a statue of Vietnam’s 6th-century military hero, Tran Hung Dao. A helipad had been created atop a building, but the South Vietnamese navy had placed a 50-caliber machine gun on the top of a building next door. It was decided that the machine gun might be used against departing U.S. choppers, so the evacuation point was abandoned.

I made my way to the U.S. Embassy, thinking that might be an option for catching a chopper out. It was surrounded by thousands of furious Vietnamese demanding to be let inside the embassy compound. There was no way I would push my way through that mob.

I trudged down Hai Ba Trung Street. The temperature was already close to 100 degrees, and my shirt was soaked with sweat. Eventually, I made my way to an alternate evacuation point—the University of Maryland’s Saigon Education Center. It was padlocked. I waited. Finally, at 12:20 p.m., two olive-drab buses arrived, and I climbed aboard along with about 60 other members of the Saigon press corps.

The two buses then began an aimless voyage through Saigon. Every few blocks, they stopped, and the Marine assigned to our bus asked for instructions on his two-way radio.

“What’s this, the Graham Martin sightseeing excursion?” someone quipped.

The UHF radio in the U.S. Marine’s hand crackled. It was “Dodge City” again.

“We’re in trouble here!” a voice said. “There are 20,000 people at the front gate of the embassy. It’s getting hostile.”

“What should I do with my bus?” our Marine driver shouted into his radio.

“Looks like Tan Son Nhut’s your only option,” came the reply. “Don’t come here!”

“Roger that,” the Marine said. Then, turning to the 60 people jammed on the bus, he said. “Looks like we’re going to the airport.” In the distance, we could hear the explosion of rockets and mortar shells slamming into Tan Son Nhut.

As the bus approached the main gate of the airbase, we could see black pillars of smoke rising from the runway. Then, Vietnamese guards at the gate began firing their M-16s into the air. We lunged for the floor.

A Rendezvous at “Pentagon East”

Our Marine escort, code-named “Wagonmaster,” yelled into his radio for instructions. “This looks bad. What should we do? What is the situation at MACV HQ?”

”It ain’t good,” the radio crackled. “We are taking mortar and artillery fire. Bust through the gate if necessary and then drive like hell.” The radio crackled, and as an afterthought, a voice said: “Good luck.”

MACV was short for Military Assistance Command Vietnam and was often referred to as “Pentagon East.”

I seriously considered getting off the bus and walking the 7 or 8 miles back to the city. Before I could, the driver moved the bus back some 100 yards from the gate.

“This is it,” he yelled. “Keep low. We’re busting through the gate!” He stomped on the accelerator, and the bus lurched forward. We bore down on the gate at about 60 mph, and we expected the guards to start shooting. Instead, they inexplicably backed off and opened the gates seconds before the lumbering vehicle would have rammed through them.

Off to one side, a downed Huey helicopter, with one skid broken off, lay on its side with its motor running and its tail rotor still spinning.

We watched a Vietnamese C-119 transport plane somehow lift off from the cratered runway, and we applauded the pilot’s skill. Our applause turned to horror seconds later when a heat-seeking missile streaked skyward, slammed into the transport, and sent it plummeting toward what looked like the Cholon section of Saigon.

As we pulled up to the MACV HQ compound, a 122 mm rocket punched into the Air America terminal across the road, showering us with debris.

I was in the back of the bus, trying feverishly to get the locked emergency rear door open, when another rocket exploded maybe 500 yards away, pelting the area with red-hot shrapnel. By this point, I was on my back, kicking with all my strength at the door.

Finally, I managed to kick the door open. I slid down to the ground and waited a few minutes, using the bus as cover. Most of the press corps had already made it into the building. I took a deep breath, then began my sprint over some 50 feet of open ground to the DAO building. Another rocket slammed into the road a few yards behind me. I dove to the ground and flattened myself on the hot concrete. I could hear razor-sharp metal shrapnel slicing through the air behind me. I pulled myself up a few seconds later and scuttled like a crab toward the door.

Once inside, we crouched along the interior hallways and waited. A couple of hours went by. Several Marines handed out paper bags and told us to write our names and next of kin on them and attach them to our clothing.

“These are for you, not your luggage,” they said. I knew what they were. I had seen them before—attached to the bodies of battle casualties.

Outside, a constant deluge of rockets, mortars, and artillery shells rained on Tan Son Nhut and the DAO compound. I closed my eyes and managed a few minutes of sleep between explosions.

It was almost 6 p.m., some 14 hours since the final bombardment of Saigon had begun. I was exhausted. I was sure every ounce of adrenalin in my body was used up. I thought about the C-119 I had watched get knocked out of the sky by a SAM-7 missile and wondered if I had made the right choice. Maybe I should stay. After all, during one of the Saturday briefings at the Viet Cong compound at Tan Son Nhut, which was established as part of the 1973 Peace Accords, Col. Ba had told me all correspondents would be treated as “guests” by the conquering North Vietnamese Army.

“We are not barbarians like the Khmer Rouge,” Col. Ba said, referring to the news of the carnage in Phnom Penh that was beginning to filter into Saigon. “Just remain in your hotel room, and someone will come for you. Those who earn an honest living will be welcome.”

Of course, I had not remained in my hotel room. I was inside the MACV compound, more than 7 miles from the Continental Palace Hotel. How would I get back to the city center? Catch a ride on an NVA T-54 tank? Hardly.

“Đi, đi ngay! Go, go, now!”

The shelling outside intensified. The huge DAO building trembled as one mortar shell after another punched into the ground near the compound. I was on the verge of getting up and walking back to central Saigon when a Marine captain walked into the corridor and bellowed:

“OK, this is it! We’re moving out! Đi, đi ngay. Go, go, now!”

We spilled out of the MACV building. Two Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion heavy helicopters waited on a tennis court about 300 feet away, their blades whooshing slowly in the hot, sticky air. After what seemed an eternity, I and about 80 others scrambled up the rear loading ramp and squatted on the floor and canvas bench seats. Seconds later, the loadmaster raised the ramp, and we lifted off.

We flew low at first, and then the pilot put the helicopter into a steady climb. I stood up and looked down at Saigon over the door gunner’s shoulder. The city seemed bizarrely peaceful and idyllic, with the Saigon River meandering through it and toward the South China Sea some 50 miles away.

Forty minutes later, we landed on the USS Denver deck, a Landing Platform Dock about 35 miles off the coast of Vung Tau.

For the next several hours, we watched one helicopter after another arrive. Some unauthorized South Vietnamese army helicopters were allowed to land and then were pushed over the side into the sea.

Eventually, with the ship’s deck filled, Vietnamese pilots were no longer allowed to land, so they would fly their Hueys to within 100 yards of the ship, open the doors, and jump into the sea along with their passengers. The chopper would remain in flight for a few moments and then pitch into the ocean-sometimes dangerously close to those swimming toward our ship.

At 4:58 a.m. on April 30, Ambassador Martin closed the embassy, destroyed its communications equipment, and climbed aboard a helicopter on the embassy roof.

The helicopter pilot sent a message to the fleet: “Lady Ace Zero Nine, Code Two is aboard.” Lady Ace Zero Nine was the chopper’s call sign; “Code Two” was the designation for an ambassador.

At 7:52 a.m., the last chopper lifted off from the U.S. Embassy roof, carrying out the small detachment of Marines who had guarded the embassy compound and engaged terrified Vietnamese in a running floor-by-floor holding action throughout April 29 and early April 30.

As the last Huey lifted off, the pilot radioed Saigon’s final official U.S. message: “Swift-Two-Two is airborne with 11 passengers. Ground security force is aboard.”

Then, the radio crackled again: “Bye-bye, Vietnam,” a voice said. “Bye-bye for now.”

Aboard the USS Denver, several of us looked at one another in stunned silence. The longest war of the 20th Century was finally over. Our emotions ran the gamut: relief, guilt, anger, disgust, joy, sadness—depending on who you were, what your politics were, and from what country you were.

“So this is what the light at the end of the tunnel looks like,” I said to no one.

I then went below deck to write my final story about America’s war in Vietnam—except it wasn’t.

I am still writing the final story 49 years later. You just read it.

–30–

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to ForeignCorrespondent and tell your friends to subscribe. IT’S FREE! WHAT A DEAL! If you’ve received this from a friend and would like to be added to our distribution list for future blog posts, please enter your email address in the sign-up for notifications box at https://ronaldyatesbooks.com/category/foreign-correspondent.

You can also find my commentaries on Substack at https://ronyates.substack.com/ and the American Free News Network at https://afnn.us.

Please feel free to comment. WE LOVE COMMENTS!

Great column, Ron. Even after 47 years, your account is so fresh and vivid I can imagine Walter Cronkite intoning, “April 29th, 1975—the evacuation of Saigon—all things are as they were then, except you are there.” Some of your readers may not know that among the 105 journalists who died covering the Indo-China conflict was Sean Flynn, son of Errol Flynn. He remains MIA 52 years after he was last seen approaching a group of VC on Highway One.

Thanks for the comments, J.C. I never knew Flynn, but I do know how he and another photog rode their motorbikes toward a V.C. checkpoint and never returned. Tim Page, a British photog who knew both well, believes the V.C. turned them over to the Khmer Rouge, who then killed them. The K.R. was notorious for killing hacks during the war. There are some stories you just never forget. The Fall of Saigon is one of those for me. I remember everything that happened that day as if it were yesterday.

Great to actually get an accurate account of the situation and events. I had far too many friends come back under flags….or not come back at all.

You are not alone in that regard, Joe. During 20 years of fighting in Afghanistan, 2,401 Americans died, but during just 8 years in Vietnam, more than 58,000 Americans died. And in neither place, there was never a political will to win and that’s a sad fact.

During LINEBACKER and other campaigns in the 60’s and early 70’s, I was stationed at the Intelligence Center in Pearl Harbor but during three tours there I was deployed probably half of the time. My only direct experience in the war was for three months bouncing from ship-to-ship in the Gulf, training EW operators and giving threat briefs to ship’s officers and commands. After the war I used to hear the comment concerning the military, “Well, you all lost that war!” and it always pissed me off as my response was “No, Washington lost the war!” Had the military been allowed to fight the war in the way we were taught, it would have been over in short order. If we had been allowed to (1) bomb the dikes, (2) bomb the rail lines from China, (3) mine the North’s harbors, (4) conduct continued bombing of the North, and (5) blockade all shipping into the North, and finally (6) allow the military to select targets up North, not Johnson and McNamara, then we would have won. Now that’s not to say that when we pulled out they wouldn’t come south, but not our problem then. Look at the record, when we started to really hit them up North and mined the harbors, the North right away quit and signed the peace accord. We (military) did some dumb things in that war, and really in all wars dumb things go on, but had we been allowed to fight as we were taught and had historically done, a lot less number of people would have died.