If there is one thing most authors have in common, besides the sheer agony that sometimes accompanies the writing process, it is the dreaded Rejection Letter from an agent or publisher.

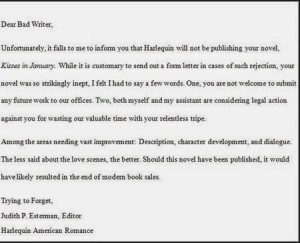

I don’t know who got this one from Harlequin, but it had to be devastating to the person receiving it.

I have received a few rejection letters–though none like the one from Harlequin.

Most authors–even wildly successful authors–have also received their share of rejection missives.

Don’t believe me?

Just take a look at this list of rejection letters sent by publishers and agents to world-renowned, Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning authors. It is simply part of the creative process, and you need to keep moving ahead–just as these authors did.

- “The American public is not interested in China,” a publisher wrote Pearl S. Buck. Her book The Good Earth became the best-selling US novel for two years running in 1931/32, and won The Pulitzer Prize.

- Alex Haley writes for eight years and receives 200 consecutive rejections from publishers and agents. His novel Roots becomes a publishing sensation, selling 1.5 million copies in its first seven months of release and selling 8 million.

- “He hasn’t got a future as a writer,” a publisher opines. Yet, the publication of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold led to its author, John le Carré, having one of the most distinguished careers in literary history.

- “Hopelessly bogged down and unreadable,” a publisher tells Ursula K. Le Guin in a 1968 rejection letter. She was not deterred, and her book The Left Hand of Darkness becomes just the first of her many best-sellers and is now regularly voted as the second-best fantasy novel of all time, next to The Lord of the Rings.

- The Christopher Little Literary Agency receives 12 publishing rejections for their new client until the eight-year-old daughter of a Bloomsbury editor demands to read the rest of the book. The editor agrees to publish but advises the writer to get a day job since she has little chance of making money in children’s books. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by J.K. Rowling spawns a series where the last four novels consecutively set records as the fastest-selling books in history, on both sides of the Atlantic, with combined sales of 450 million.

- “It is so badly written,” a publisher tells this author. However, Dan Brown is not discouraged and tries Doubleday, where his book makes an impression. The Da Vinci Code eventually sold 80 million copies.

- “Too different from other juvenile (books) on the market to warrant its selling,” says a rejection letter sent to Dr. Seuss. His books have racked up $300 million in sales, and he is now the 9th best-selling fiction author of all time.

- J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye was rejected multiple times by New York publishers until an editor at Little, Brown, and Company bought it. The 1951 novel has sold more than 96 million copies and has been translated into almost every major language.

See what I mean?

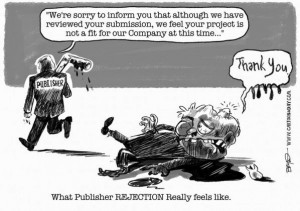

Editors, agents, and first readers who dig through the publisher’s slush pile are all capable of making bone-headed decisions about other people’s work. And they do it all the time.

So if you have a stack of rejection letters sitting on your desk or stuffed into a file cabinet, don’t despair. You are not alone.

What you should do, instead of becoming despondent and inconsolable, is read those rejection letters carefully and look for the constructive criticism in them.

In most cases, you will find some–though, as one publisher told an author many years ago: “This manuscript should be buried under a pile of rocks and forgotten for the next thousand years.” (That book went on to become a bestseller and was even made into a movie. Its name: Lolita.)

Phrases like that can be disheartening, even to the most thick-skinned scribbler. So far, I have not received anything quite so venomous though I have had my go-rounds with a few agents and editors who couldn’t see the value of a book I was working on.

Now that I am writing fiction rather than nonfiction, I am finding that I no longer care what an agent or publisher may think of my work. I find that incredibly satisfying when I can see that customers on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Goodreads like my books and give them mostly 5-stars with a handful of 4-star ratings.

That tells me that I must be doing something right.

The key is believing in yourself and the story you are telling. You will NEVER please everybody. There will always be those who don’t understand or don’t like your book or books. That’s life. But it would help if you didn’t stop believing in what you are writing. Does that mean you should ignore valid and constructive criticism?

No, it does not. If somebody has taken the time to tell you what is wrong with your book or why they didn’t like it, you should also take the time to consider that criticism and learn from it.

It doesn’t mean you should give up, stop writing, and walk away from your computer. Writing is a skill that cannot be taught–at least not in the same way one learns calculus or biology.

It must be learned. And we learn to recognize good writing by reading.

Then we learn how to write by writing, writing–even if the writing we do is terrible, with too many adjectives in place of solid action verbs or too many compound-complex sentences that give readers migraines as they slog through page-long paragraphs.

Reading should be fun–not a chore. And only you, the writer, can dictate that.

So if a rejection letter says your prose is ponderous and pretentious, or your story is tedious and byzantine, you might want to take a hard, critical look at what you have written.

And after doing that if you still disagree with the author of that rejection letter, then, by all means, plow ahead. You may be right, and that agent or editor may be wide of the mark.

Time and book sales will tell.