“Has America Ever Been as Divided as it is today?”

That was the rhetorical question a television pundit recently asked during a discussion of the nation’s current hateful political climate.

Frankly, the question surprised me. Then I looked at who asked it. She was a thirty-something talking head who had little or no historical perspective of this country.

For her, and for those who may have only vague memories of the 1960s, the answer to that question is likely “no.”

But for many of us who lived through the 1960s and early 1970s and who were on college campuses back then, the answer is a resounding “yes!”

Yes, the nation has been this deeply divided—not only this deeply divided but almost ripped in half by something called the Vietnam War, by an active, sometimes violent civil rights struggle, and by a painful generation gap that seemed all but unbridgeable.

Indeed, the social fabric of America between the years of 1961 and 1975 was about as tattered as I have ever seen it. Of course, I was not around during the Civil War (1861-1865) when the country WAS divided—politically, culturally, and geographically.

But let’s focus on the 1960s, not the 1860s. The music of Bob Dylan was an anthem for the counterculture revolution. Haight-Ashbury and Woodstock were the emblematic settings of a time when flower-power hippies, tie-dye-wearing revolutionaries, and other social-political rebels gathered to burn incense, drop acid and profess their adherence to peace and love.

“Don’t trust anybody older than thirty,” warned leaders of the counterculture—street revolutionaries. Meanwhile, The Weather Underground, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the Black Panthers were blowing up buildings, robbing banks, and attacking and killing police.

During one 18-month period between 1971 and 1972, there were 2,500 bombings in the United States by radical groups. The Weather Underground bombed the U.S. Capitol building in 1971, the Pentagon in 1972, and the U.S. State Department in 1975.

Some students and even some faculty on college campuses are the living by-products of this raucous and intense era—though I doubt if many of their middle class and middle-aged parents who find themselves knee-deep in mortgages and college loans are eager to “fess up” to have been one of America’s ubiquitous “if it feels good, do it” flower children.

As a student at the University of Kansas and as editor of the University Daily Kansan (K.U.’s student newspaper), I watched demonstrators engage in running battles with Chicago cops during the 1968 Democratic convention. Police wielding cudgels cracked open heads, and the streets were blood-soaked. Protesters retaliated by throwing plastic bags filled with human feces at police. Reporters called those protesters “waste baggers.” The cops had other names for them.

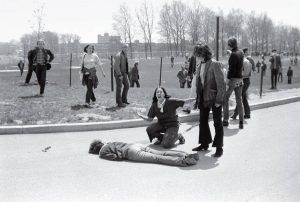

Back on campus at the University of Kansas, angry students in 1970 burned down the Student Union. It was a residual gesture aimed at showing solidarity with four Kent State University students who were killed and nine who were wounded May 4, 1970 when Ohio National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of students who were demonstrating against President Nixon’s decision to bomb Cambodia—a move that was seen as an expansion of the Vietnam war.

Not long after that, as a Chicago Tribune reporter, I covered what seemed like the “demonstration of the week” as protesters took to the streets again and again to protest an infinite menu of social, racial, ethnic, political, environmental and economic evils.

Unlike today, when police have opted to allow protesters to destroy property, loot, and burn entire city blocks to the ground, the protests I covered in Chicago were met with unflinching and deadly force. It was Mayor Richard J. Daley’s City, and he was not going to allow protesters to overturn cars, loot, and burn buildings.

I recall covering a Weather Underground demonstration on October 8, 1969, when some 300 so-called “Weathermen” rioted through Chicago’s affluent Gold Coast area. They smashed windows, overturned cars, and tried to set fire to buildings. The mob rampaged four blocks until they came to police barricades.

That didn’t stop them. Foolishly, students charged the police, whose numbers had swelled to more than 1,000. The police quickly counter-attacked. Unlike 1968, these protesters came prepared, many wearing motorcycle and football helmets. However, Chicago’s police were well trained and better armed. It was no contest.

Tear gas choked the streets, and when protestors gathered to counter-attack, police ran squad cars into the mob, sending them flying in all directions. Thirty minutes later, the rioting was finished.

Even though 28 policemen were injured in the melee, there was little doubt who had won. Police shot six Weathermen, and an unknown number were wounded. About seventy rioters were arrested.

Was America ever as divided as we are today? Are you kidding? How many protesters do police shoot today for attacking property or looting?

Check out any library that maintains digital or microfiche versions of newspapers and magazines of the 1960s and 1970s. Today, the divisions seem like minor abrasions compared with the gaping wounds that marked America 40 or 50 years ago.

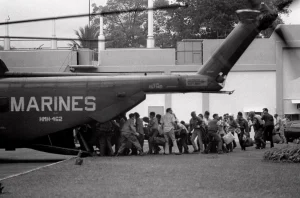

It wasn’t until the last choppers lifted off Saigon roofs on April 30, 1975, that the healing began. The war in Vietnam was over—finally, after almost 15 years of American involvement.

I had been a soldier during part of that era, and between 1974 and 1975, I was covering the fall of South Vietnam and Saigon for the Tribune. As some 200,000 Communist North Vietnamese troops marched into Saigon and a U.S. Marine CH-53 Sea Stallion chopper carried me down the Vung Tau corridor to the waiting U.S. 7th Fleet, an almost palpable sense of healing and reconciliation swept over America.

That didn’t resolve the guilt, anger, and grief many Americans felt about their nation’s abortive crusade in Vietnam. Indeed, we are still dealing with those issues more than 40 years after those choppers carried the last Americans out of Saigon. After all, more than 58,000 Americans died in that war, and another 300,000 were wounded. Vietnamese casualties on both sides were in the millions.

The yawning schisms of 40 years ago, for the most part, have been filled in by the relentless sands of time.

I am still amazed by that healing process. As a student in the 1960s, I was sure the nation would never recover from the terrible wounds of Vietnam. Of course, this country’s ability to heal itself is one of those things that make the U.S. so remarkable.

Americans are resilient people. But we have short memories. And because we have short memories, we repeat many of our mistakes and sometimes open old wounds.

Most wounds leave scars. We are adept at covering up those scars, but we forget what caused the injuries in the first place.

So when a television analyst asks if America has ever been so divided as it is today, my answer is absolute—look for the scars. And try not to repeat the mistakes that made them.

Someone once said that good journalism is a nation talking to itself. Today, it seems that kind of journalism has been replaced by a country screaming at itself.

Good journalism is not only a conversation about what is happening today and what may happen tomorrow, but it also should provide a translucent lens to the past. And above all, it needs to do all of those things fairly and without bias.

To paraphrase George Santayana: when we cannot see or remember the past, we are condemned to repeat its mistakes—and to ask such questions as: “Has America Ever Been as Divided as it is Today?”